Focus on west Cumbria: 'A long-forgotten spot' with ambitions for the future

- Published

St Bees in Cumbria is the start of the popular coast to coast walking and cycling route

Cumbria is known globally for the Lake District, but to the west lies an often-overlooked land. West Cumbria is home to the county's largest employer - the Sellafield nuclear site - while also having higher than average pockets of unemployment. The BBC is focusing on west Cumbria, which stretches from Ravenglass in the south to Silloth in the north. But where exactly are we talking about and what has happened there?

On a sunny day, St Bees Head offers the perfect panorama.

To the south, across a curved blue bay, sits the enormous yet eerie Sellafield site, its tall towers and monolithic buildings clearly visible, not to mention the distinctive round reactor known as the Golf Ball.

Looking out to sea you can see the Isle of Man, a distant haze of mounds some 30 miles to the west, and further north across the Solway Firth, the imposing hills of Dumfries and Galloway.

East and inland shows a patchwork of green fields, a wind turbine or two, then the striking fells of the west Lake District, the distinctive shapes of Great Gable and Scafell Pike clearly discernible.

The orb of Windscale's Advanced Gas-cooled Reactor at Sellafield is very distinctive

While some aspects of this view have been fixed for thousands of years, much has also changed in this part of the world.

The Romans and Vikings settled here, but it was really in the Georgian period, when the local landed gentry realised the profits to be made from mining and exporting coal, that the fishing villages and farming hamlets gave way to an explosion in industry.

The Senhouse family oversaw the transformation of Maryport from a fishing harbour into a major dock, from where coal hacked from beneath the surrounding fields could be transported to places like Ireland.

Maryport grew in size and standing in the Georgian period thanks to coal mining and shipping

A railway, designed and built by pioneering engineer George Stephenson, brought coal in from further afield and a town to support the industry rapidly grew.

It was also home to three shipyards and a lighthouse, built in 1836, not to mark hazardous rocks but rather to indicate if the tide was in or out for sailors at sea looking for berth.

"For a long-forgotten spot we have got a lot of history," Peter Stevenson, head of Maryport Maritime Museum, said.

Under the watch of the Curwens, an ancient family who had fought at Agincourt and against William Wallace, Workington became the "industrial capital of England" according to Steve Jones from the town's Helena Thompson Museum, external.

Workington had already had a rich history - Mary Queen of Scots stayed there for a night or two (exactly how long is disputed) in May 1568 after sailing across the Solway, her final nights as a free woman before being arrested by Queen Elizabeth I's forces.

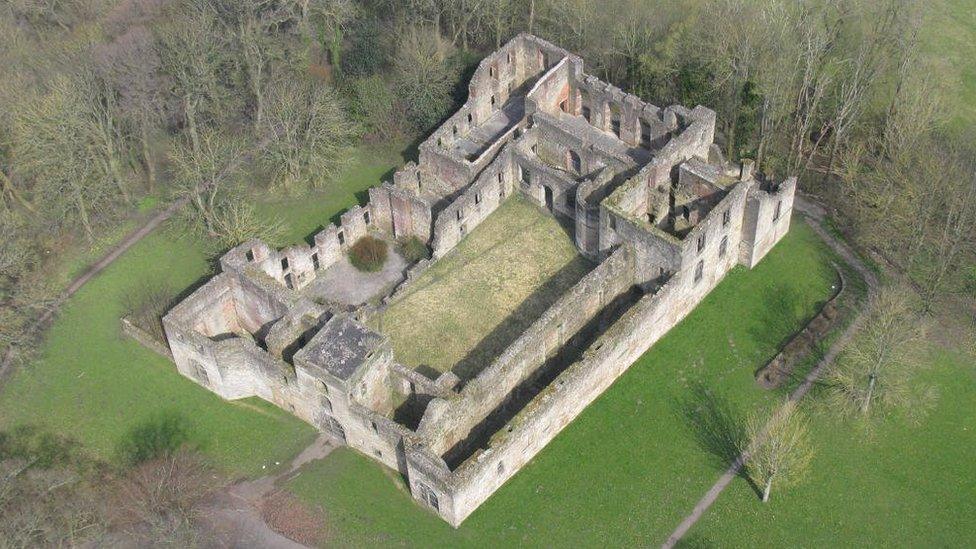

The Curwen family lived at Workington Hall, but it has fallen into ruin since it was used by the army in World War Two

Workington was also the birthplace of modern agriculture, Mr Jones said, pointing out of the window to an impressive looking collection of stone barns and crenelated gateways on a small hill half a mile or so from the museum.

Schoose Farm was where John Christian Curwen, a cousin of Cockermouth-born HMS Bounty mutineer Fletcher Christian, pioneered such methods as ploughing, crop rotation and improved animal husbandry.

"Much of what he did there is still used today," Mr Jones said.

But it was the mining and exporting of coal that really saw Workington boom.

People came from across Britain, miners from Wales and the West Country, ship builders from Scotland and the North East and labourers from the Midlands.

Workington was built around its coal mines and harbour

The area's rich resources and sea access brought other industries, most notably steel works which operated for 130 years before closing in 2006.

Victorian steel pioneer Henry Bessemer opened works in Workington using his Bessemer Converter to make steel railway lines that were used across the world.

Ship building became a major industry, with nearby Harrington going from a small harbour village to a major hub sending ships around the world.

Cumbria's ships transported coal out and brought coveted goods such as rum and tobacco in, but they also moved people.

The Beacon Museum in Whitehaven tells the history of the town, west Cumbria and the Sellafield site

Whitehaven was the fifth most active British port involved in the trans-Atlantic slave trade according to the town's Beacon Museum, and between 1710 and 1769 69 ships left the harbour carrying textiles, firearms and metalwork to be traded for slaves.

"Whitehaven merchants participated in the slave trade at times when other trades, such as tobacco or coal, were less profitable," a sign in the museum said, adding: "But Whitehaven struggled to make the vast profits seen in Liverpool because of its remote geographical location."

The town of Whitehaven is a model of Georgian design, its grid-style streets said to be an inspiration for those of New York.

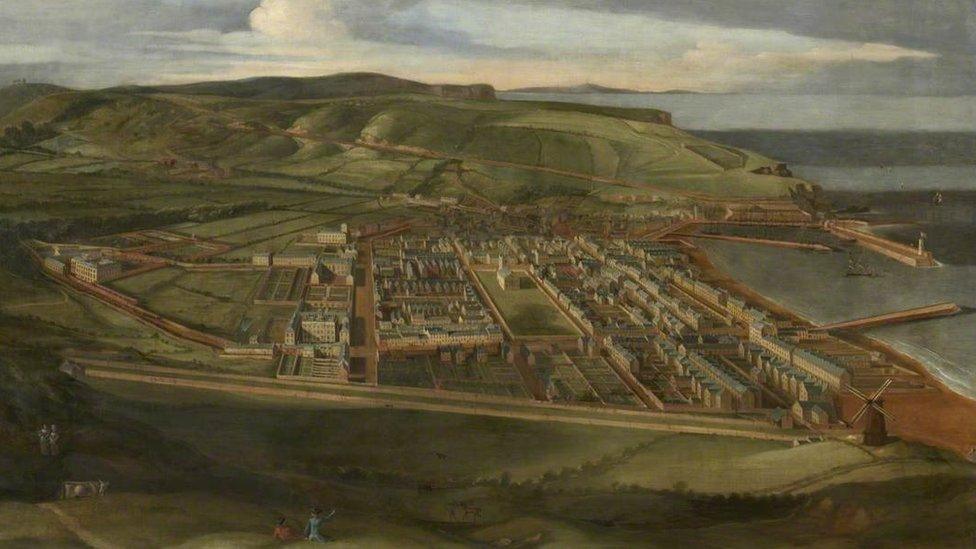

Whitehaven's grid-layout is said to have inspired the construction of New York

But while it was being hailed as "one of the most handsome towns in all the northern counties" by the Parliamentary Gazette in 1845, its success also brought problems, most notably overcrowding and diseases such as cholera.

The town's population rose from 8,472 in 1801 to 19,044 by 1911, with the poorer houses becoming crammed with people, which led in turn to investments in new hospitals and healthcare.

Artist Matthias Read painted Whitehaven in 1736

Much of its fine period architecture remains, although most of the old industry is long gone with the decline of coal and steel production.

As Cumbria entered the 20th Century, new companies came, and World War Two saw something of a revival in west Cumbria's fortunes, with the area's seclusion making it an ideal place to build weapons and bombs "out of the range of the German bombers," Mr Jones said.

Silk parachutes and military uniforms were made in Whitehaven, while world-famous Kangol started making berets in nearby Cleator Moor in 1938.

A lot of Whitehaven's Georgian buildings remain

Parts for Spitfires and other metal weaponry were made at Distington while Royal Ordnance Factories were built in Hycemoor, Drigg and, most notably given what was to follow, Sellafield.

Before the war, Sellafield was a collection of farming hamlets, but after it became the centre for Britain's nuclear projects thanks again to its remote location and access to water.

In 1947, the Windscale reactors, part of Britain's development of nuclear weapons, opened followed by the neighbouring Calder Hall nuclear power plant in 1956.

On 10 October 1957, a fire broke out in one of the Windscale reactors spewing out radioactive material across much of the UK and Europe, although much wider devastation was spared thanks to the installation of two filters, known as Cockcroft's Follies due to the widely misheld perception they were unnecessary, to two exhaust shafts.

It remains the UK's biggest nuclear disaster and is estimated to have caused between 100 and 240 cancer deaths, while millions of gallons of milk from a 200-square mile area was destroyed amid fears of contamination.

The Sellafield site has more than 1,000 buildings

Sellafield then became the country's nuclear reprocessing plant, bringing in used fuels from UK power plants to house safely, while decommissioning is also being carried out on the remnants of the 1950s nuclear age.

Some 11,000 people now work at Sellafield with a further 13,000 in its supply chain.

It is the area's largest employer by some distance and without it you could "kiss goodbye" to west Cumbria, Mr Jones of the Helena Thompson Museum said.

Tantamount to a town, it covers 700 acres and comprises more than 1,000 buildings with an array of nuclear works carried out there.

Cockermouth is one of the places to become a "dormitory town" for Sellafield with many workers making the commute, according to Cockermouth historian Eric Cass.

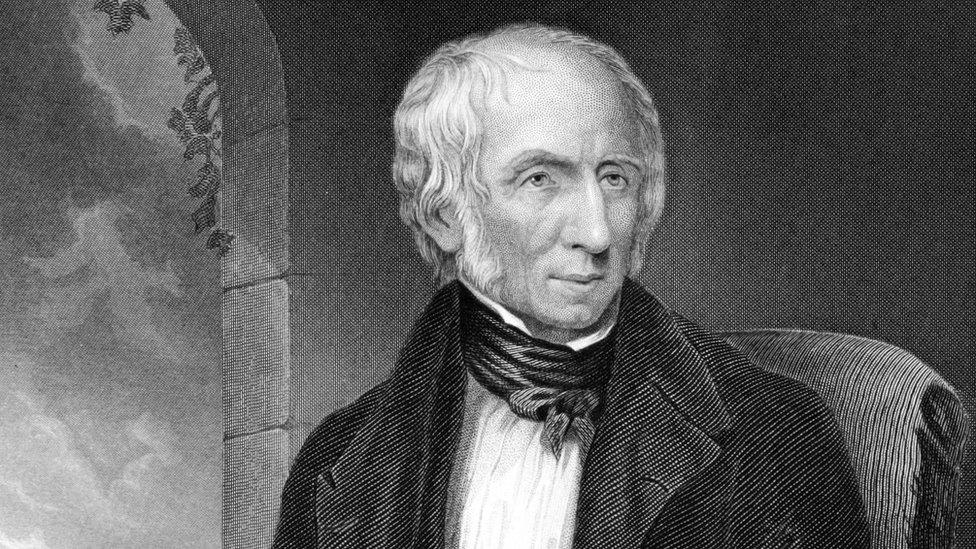

William Wordsworth was born in Cockermouth

The town on the northern edge of the Lake District began as a castle and market, with sales beginning at 11:00 every Monday to give people from surrounding villages time to get in before the bargains had been snapped up.

In the 1800s its two rivers, the Cocker and Derwent, brought linen and cotton mills and in 1940 Millers shoes relocated to the town from Great Yarmouth to escape bombing raids.

The shoe factory closed many decades later and the town's biggest employer now is a gasket factory.

William Wordsworth was born in Cockermouth, and the poet's birthplace Wordsworth House is one of the attractions hoping to lure tourists away from the "honey pot" of the Lake District, Mr Cass said.

"It was a very important place in its day," he said.

Some 11,000 people work at the Sellafield site

Elsewhere, there is a mixed picture of stunning landscape and deprived communities left in the wake of closed industries.

West Cumbria was designated a Special Area in 1934, one of several such places in the UK earmarked for extra government investment to improve the local economy and entice other businesses in.

The area's isolation and lack of "nearby cities to provide focal points for growth" saw it called the "Cinderella of the Special Areas", according to academic May Evelyn Clarke, external who said the "puny" scheme "made very little difference to the lives of the people of industrial West Cumberland".

Though there have been some improvements, many of the problems remain, most notably it being somewhat out on a limb with the Lake District a beautiful but big buffer.

There is a desire to drag more of the Lake District's millions of annual visitors further west

Efforts are being made to revitalise the area's industry today however, not least through the wind farms visible at various spots both on and off shore.

Dubbed the Energy Coast, the aim is to make west Cumbria a "globally competitive energy and environmental cluster" according to a government masterplan, external.

There is also tourism and a desire to drag more of the Lake District's millions of annual visitors a few miles west.

"You can understand why now people only think of the Lake District," Mr Jones said, although, he added, the museum still gets a decent number of visitors on rainy days when the fells are not nearly so inviting.

"But we are very proud of history even if it is not as widely known about as it should be," he said.

Whitehaven is known as a Gem Town thanks to its historic buildings

Whitehaven is home to several museums and a bustling marina, and although there are a number of vacant shops on its main shopping streets, the town is one of England's 40 Gem Towns, a designation given by the Council for British Archaeology in 1964 to places deemed to be "particularly splendid and precious".

Maryport also has much to offer according to Mr Stevenson.

"The harbour is beautiful," he said, adding: "We have got the best sunsets in the world, I can guarantee you that."

Maryport's sunsets are said to be the best in the world

Follow BBC North East & Cumbria on Twitter, external, Facebook, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to northeastandcumbria@bbc.co.uk, external.

- Published5 September 2022

- Published4 November 2014

- Published25 November 2011