Bronze Age wheel at 'British Pompeii' Must Farm an 'unprecedented find'

- Published

Jo Black: The discovery reveals the ''complex and sophisticated life'' of our Bronze Age ancestors

A complete Bronze Age wheel believed to be the largest and earliest of its kind found in the UK has been unearthed.

The 3,000-year-old artefact was found at a site dubbed "Britain's Pompeii", at Must Farm in Cambridgeshire.

Archaeologists have described the find - made close to the country's "best-preserved Bronze Age dwellings" - as "unprecedented".

Still containing its hub, the 3ft-diameter (one metre) wooden wheel dates from about 1,100 to 800 BC.

The wheel was found close to the largest of one of the roundhouses found at the settlement last month.

Its discovery "demonstrates the inhabitants of this watery landscape's links to the dry land beyond the river", David Gibson from Cambridge Archaeological Unit, which is leading the excavation, said.

Archaeologists worked on a wooden platform as they uncovered roundhouses at the quarry last month

Historic England, which is jointly funding the £1.1m excavation with landowner Forterra, described the find as "unprecedented in terms of size and completeness".

"This remarkable but fragile wooden wheel is the earliest complete example ever found in Britain," chief executive Duncan Wilson said.

"The existence of this wheel expands our understanding of Late Bronze Age technology, and the level of sophistication of the lives of people living on the edge of the Fens 3,000 years ago."

It is not yet known what type of wood was used to construct the wheel

The dig site, at Must Farm quarry near Whittlesey, Cambridgeshire has been described as "unique" by Mr Gibson.

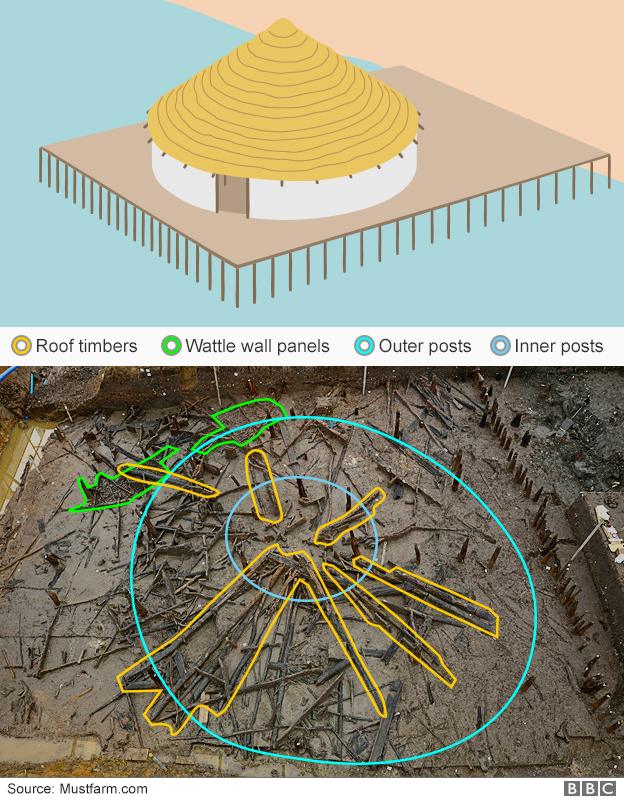

It has proved to be a treasure trove for archaeologists who earlier this year uncovered two or possibly three roundhouses dating from about 1,000-800 BC.

The timbers had been preserved in silt after falling into a river during a fire.

The Bronze Age wheel is said to be the largest, earliest complete example of its kind ever found in Britain

A close-up of the hub at the centre of the wheel

The wheel was found close to one of the settlement's roundhouses

Kasia Gdaniec, senior archaeologist at the county council, said the "fabulous artefacts" found at the site continued to "amaze and astonish".

"This wheel poses a challenge to our understanding of both Late Bronze Age technological skill and - together with the eight boats recovered from the same river in 2011 - transportation," she said.

The spine of what is thought to be a horse, found in early January, could suggest the wheel belonged to a horse-drawn cart, however, it is too early to know how the wheel was used, archaeologist Chris Wakefield said.

The spine of what is thought to be a horse was found not far from the wheel

While the Must Farm wheel is the most complete, it is not the oldest to be discovered in the area.

An excavation at a Bronze Age site at Flag Fen near Peterborough uncovered a smaller, partial wheel dating to about 1,300 BC.

The wheel was thought to have been part of a cart that could have carried up to two people.

Part of an older Bronze Age wheel was found at Flag Fen in Cambridgeshire

The Must Farm quarry site has given up a number of its hidden treasures over the years including a dagger found in 1969 and bowls still containing remnants of food, found in 2006.

More recently the roundhouses, built on stilts, were discovered.

A fire destroyed the posts, causing the houses to fall into a river where silt helped preserve the timbers and contents.

What does the wheel tell us?

"We're here in the middle of the Fens, a very wet environment, so the biggest question we've got to answer at the moment is 'Why on earth is there a wheel in the middle of this really wet river channel?'," says archaeologist Chris Wakefield.

"The houses are built over a river and within those deposits is sitting a wheel - which is pretty much the archetype of what you'd expect to have on dry land - so it's very, very unusual."

An articulated animal spine found nearby - at first thought to be from a cow - is now believed to be that of a horse.

"[This] has pretty strong ties if they were using something like a cart.

"In the Bronze Age horses are quite uncommon. It's not until the later period of the Middle Iron Age that they become more widespread, so aside from this very exciting discovery of the wheel, we've also got potentially other related aspects that are giving us even more questions.

"This site is giving us lots of answers but at the same time it's throwing up questions we never thought we'd have to consider."

Analysing the data from samples found at Must Farm could take the team several years, he added.

Artist's impression of what one of the roundhouses might have looked like

Other artefacts found inside the roundhouses themselves - including a small wooden box, platter, an intact "fineware" pot and clusters of animal and fish bones that could have been kitchen waste - have been described as "amazing" by archaeologists.

Archaeologists said they were "thrilled" to find a well-preserved wooden box inside one of the roundhouses

The team is just over halfway through the eight-month dig to uncover the secrets of the site and the people who lived there.

- Published6 February 2016

- Published30 January 2016

- Published12 January 2016

- Published12 January 2016

- Published12 January 2016