Snapping the Stiletto: Reimagining the 'Essex girl' cliché

- Published

Snapping the Stiletto wants to reshape the idea of what it means to be an "Essex girl"

A pioneering welfare campaigner, a divorced tobacconist and an officer on the beat are just some of the remarkable women from history whose stories are challenging the "Essex girl" stereotype.

The Snapping the Stiletto project is putting the tired cliché to rest by uncovering the tales of females across the county who blazed a trail decades ago.

More than 130 volunteers have scoured microfiche, public records and council minutes to showcase the achievements of their predecessors.

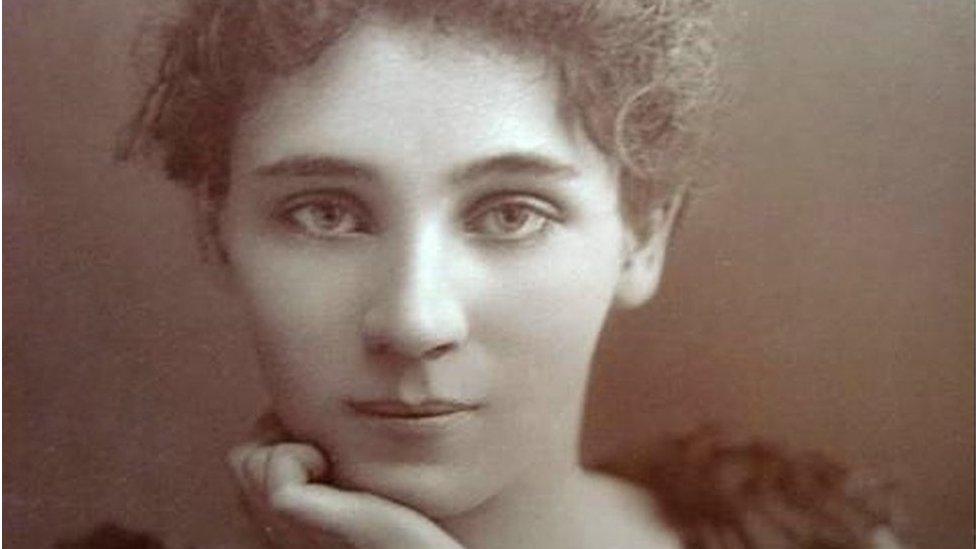

The campaigner

A mother and baby clinic was set up by Adelaide Hawken in Southend in 1915

Almost hidden in the queue, a nameless young woman is immaculate in a neat polka dot dress and straw hat - seemingly oblivious to the baby on her lap.

Her stare evokes the shock and exhaustion of new motherhood, surrounded as she is by the clamour of a typical mother and baby clinic.

Except this is Essex, circa 1915, in a clinic established more than 30 years before the NHS by local councillor Adelaide Hawken.

The welfare campaigner used her political muscle to lobby for a space in the Westcliff Institute, adjoining the Methodist church on Trinity Road, where it remains today supporting families with pre-school children.

She even persuaded Southend Town Council to fund it with £150 a year (about £15,000 today) "towards the promotion of maternity and infant welfare".

Mrs Hawken pushed for the Southend clinic 30 years before the birth of the NHS

Mrs Hawken's story would have been consigned to a few sepia-tinted newspaper cuttings were it not for Essex museums development officer Amy Cotterill, whose idea it was to ask galleries and museums across the county to get involved in Snapping the Stiletto.

At first, researchers struggled to even find out Mrs Hawken's first name - largely because museum curators were historically male and women's stories mostly related to domestic work and servitude.

Demand for welfare and support among young families in Southend was high

But records eventually revealed Mrs Hawken was a force in the community.

She was an active supporter of women's suffrage and became one of the first women in the country to be appointed as a magistrate in 1920.

Her granddaughter Dorothy - who became one of Britain's first female bank managers - remembers a "remarkable, headstrong woman", with a "warm and gentle character".

Dorothy Hawken describes her grandmother as "very loving and kind"

Iona Farrell, assistant curator at Southend Museums Service, said women like Mrs Hawken could inspire women in Essex today to "change their perceptions".

"Adelaide had a real passion for helping other people, quite a selfless person - active, very well-educated and respected by her peers.

"There are so many diverse stories of women who pioneered the way for women today, fighting for equal rights or access to healthcare, welfare and support.

"Their stories really captured everyone's interest and imaginations - their fight is still so relevant. Their legacy is still felt."

You might also be interested in:

The divorced tobacconist

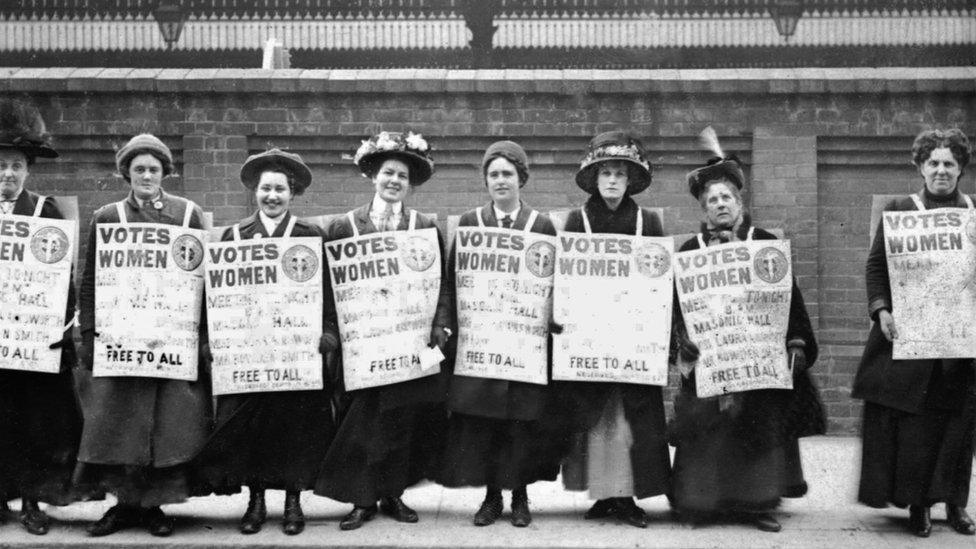

Rosina Sky, far right, was a working-class suffragette in Southend

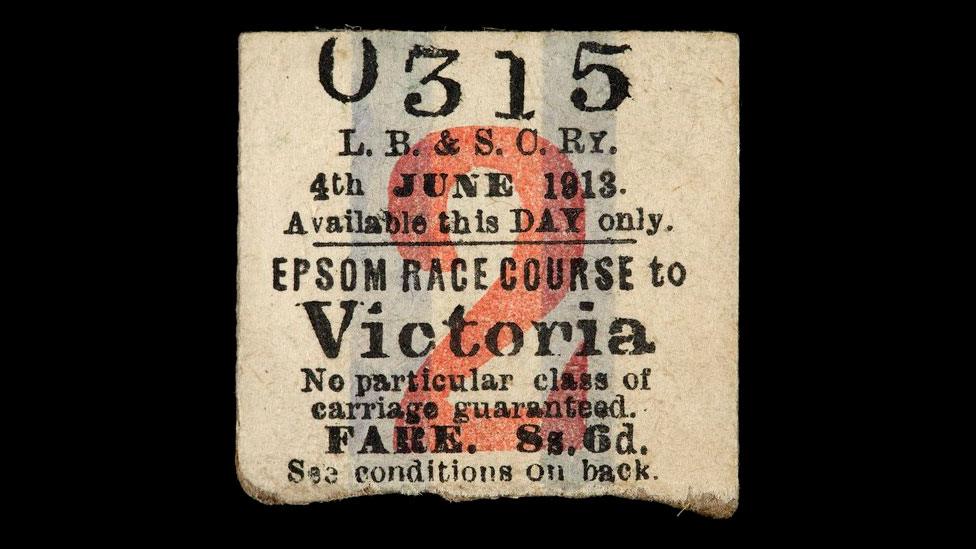

At about the same time Mrs Hawken was pioneering for welfare reform, businesswoman and suffragette Rosina Sky was fending off the bailiffs.

The divorced mother of three ran a tobacconist in Southend but despite having all the responsibilities of running a shop, had none of the financial rights afforded to men in the same position.

The divorced mother of three was a force to be reckoned with

The treasurer of the town's branch of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) was also a member of the Tax Resistance League, whose slogan was "No Vote, No Tax".

So when goods from her shop in Clifftown Road were seized and auctioned, she highlighted the injustice by promoting the sales on the streets, where according to records, her suffragette sisters bought the stock back for her.

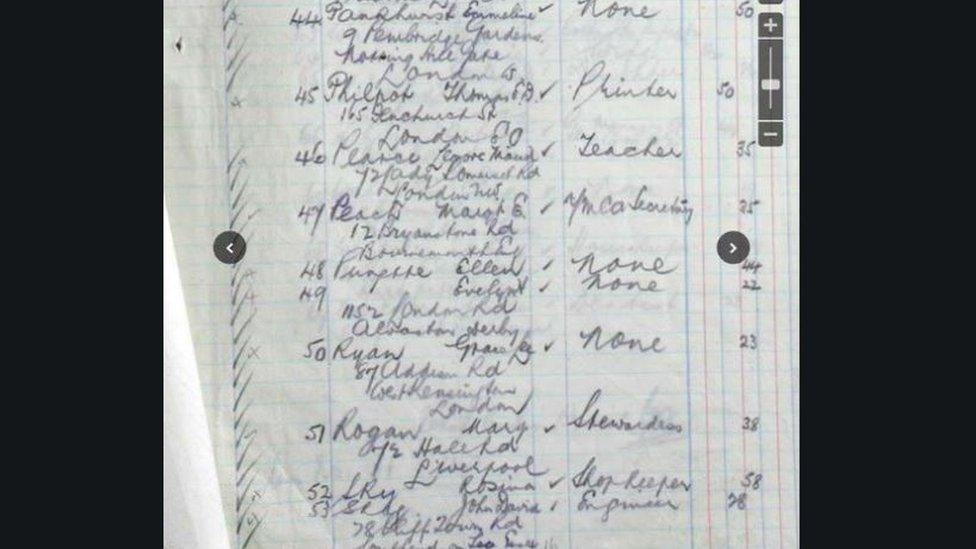

The list of passengers arriving in Liverpool from America in 1916 suggests Mrs Sky (no.52) knew Emmeline Pankhurst (no.44)

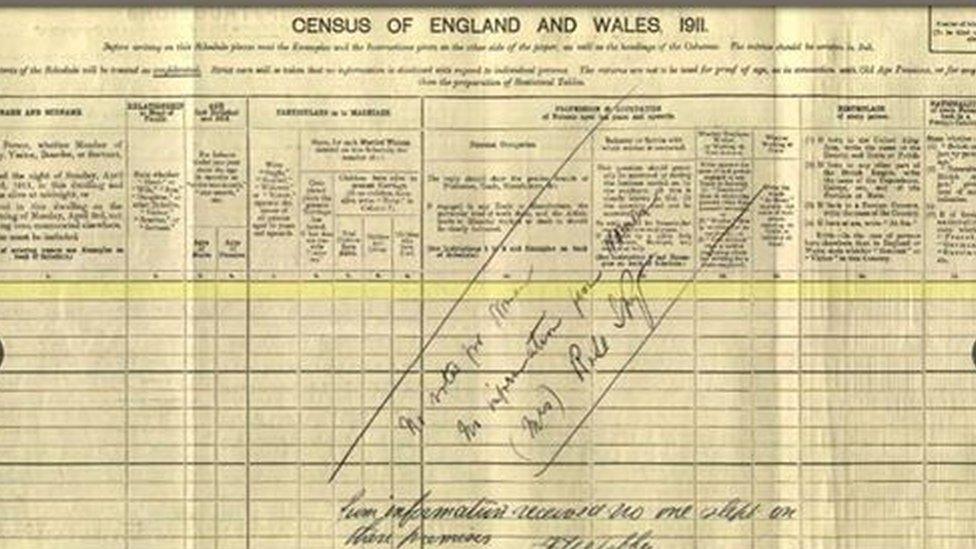

Mrs Sky spoiled her 1911 census record with the words: "No votes for women, no information from women"

Mrs Sky's story came to light after the Southend Museums service asked the Prittlewell Victoria Townswomen's Guild to help find notable local women from history.

"The volunteers loved researching Rosina's story," said Ms Farrell.

"Probate records show she left £2,628 in 1928 to her daughter. She must have been a really savvy businesswoman to build that up - as a single mum - and put herself in the public spotlight as a divorcee."

Intriguingly, Mrs Sky's name appears on a transatlantic passenger list alongside Emmeline Pankhurst, suggesting she might also have known her more famous compatriot.

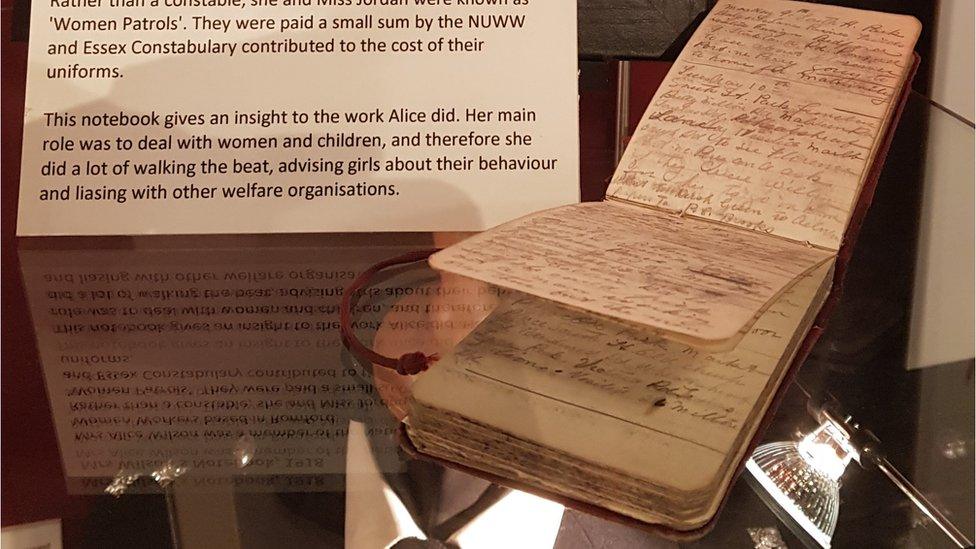

The woman on patrol

Alice Wilson patrolled the streets of Romford before women were allowed to become constables

Women were not given full policing powers until the 1940s.

But in 1918, Alice Wilson was paid a small sum by Essex Constabulary to walk the beat in Romford.

Her main role was to "advise girls about their behaviour" and "deal with women and children".

The mother of four and National Union of Women Workers member kept a meticulous police notebook.

She wrote of investigating an assault that ended in underage pregnancy, a woman charged with killing her granddaughter, and a girl found to be "carrying on with German prisoners".

Volunteers are currently transcribing the 100-year-old notes for future exhibitions.

Mrs Wilson's notebook is on display at the Essex Police Museum

Hannah Wilson, curator of the Essex Police Museum, said the notebook provided an extraordinary insight into the role of women, external in the male-dominated force.

"It was not until after 1946 that Essex Constabulary advertised vacancies for its new Women's Department - and women could only take on the same role as men from 1975," she said.

"Alice's work as part of the women's patrols is one of the first examples of women in the police force and may have helped shape the roles of future women constables."

The 'ordinary girl'

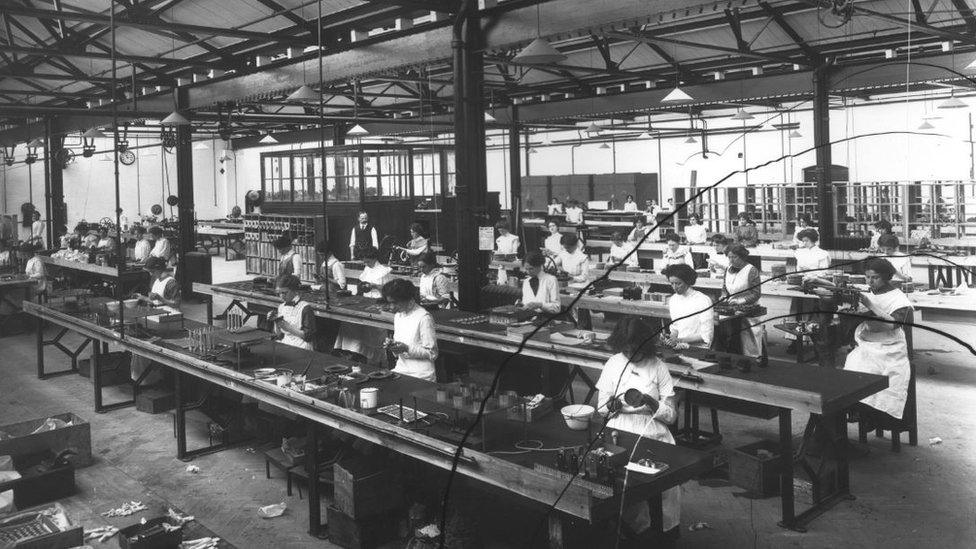

Florence Attridge worked for Marconi in Chelmsford during World War Two

It was the chance discovery of a British Empire Medal on an online auction site that illuminated the life of "an ordinary girl doing an ordinary job in extraordinary circumstances," says author and historian Tim Wander.

With the paperwork accompanying the medal, he found the customary letter from the King to its recipient, Florence Attridge, as well as a note of thanks from the Naval Intelligence Services.

The medal, which was awarded to her in 1946 for services during World War Two, prompted Mr Wander to find out more.

The winding shop inside the Marconi works in New Street, Chelmsford

He found she was a shift supervisor at the Marconi company in New Street in Chelmsford, where she managed a team winding coils for motors in radio sets.

"In 1943-44, the company became responsible for making the mechanical parts of the B2 spy sets used in the war," said Mr Wander.

"It was incredibly secretive work, with only the best ladies involved, usually in a closed-off area of the factory after hours.

"Imagine knitting with copper wire under a large magnifying glass."

The B2 radio spy sets used by the Allies during the war

Mr Wander said Mrs Attridge represented the "indomitable spirit of those who simply served".

"She would have seen friends killed in the bombings around her but continued this specialised and pressurised work for her country - in secret.

"She was extraordinary."

The British Empire Medal awarded to Florence Attridge in 1946

Such stories help to turn the idea of the "Essex girl" stereotype on its head, according to Ms Cotterill.

"This is a county of strong, inspiring women who worked hard to support themselves, their families and their communities - we have only scratched the surface.

"Their stories are being told not by the museums but by the volunteers. It is led by the women of Essex themselves."

Snapping the Stiletto, a collaboration between 12 Essex museums and galleries, will culminate in a touring exhibition in 2019.

- Published2 May 2018

- Published8 February 2018

- Published7 February 2018

- Published9 March 2017