Triple trawler tragedy: The Hull fishermen who never came home

- Published

In the space of less than a month at the start of 1968, 58 fishermen based in the English port of Hull lost their lives in three separate trawler sinkings. Thanks to the efforts of a group of determined women, the deaths would change the industry, with the ripples spreading from the Arctic Sea to the steps of Downing Street.

"I am going over. We are laying over. Help me. I'm going over," skipper Phil Gay pleaded in a final, desperate message from the Ross Cleveland, which sank while sheltering from a storm in an inlet near Isafjordur in Iceland on 4 February.

"Give my love and the crew's love to the wives and families."

The Ross Cleveland was the third vessel to sink, in what became known as the triple trawler tragedy.

The St Romanus had sunk in the North Sea on 11 January, with the Kingston Peridot lost just over a fortnight later off the coast of Iceland. The 20-strong crew aboard both ships all died.

There was a single survivor of the three sinkings, 28-year-old Harry Eddom, the mate of the Ross Cleveland, who made a daring escape from the vessel by raft along with two crewmates who ultimately perished.

"We drove down this fjord and we hit the bottom," he said in a 1968 interview.

"I got out and I pulled the raft as far up as I could up on to the rocks."

'We had no paddles... we hit the bottom of a fjord'

Eddom - who still lives in Hull - described how he managed to stumble alone to the refuge of an Icelandic farmhouse.

"When I got there it was deserted. I hadn't the energy to kick the door down... so I just waited and went to the back of it to get out of the snow."

Described in a Daily Express headline as the "Man who came back from the sea", he was feted on his return before public opinion turned against him.

There were deeply unfair suggestions he should have given his waterproof clothing to a teenage crewmate who made it into the lifeboat wearing only underwear, while some seemed to judge him simply for being alive.

Within a few weeks Eddom was back at work, as if the tragedy had never occurred.

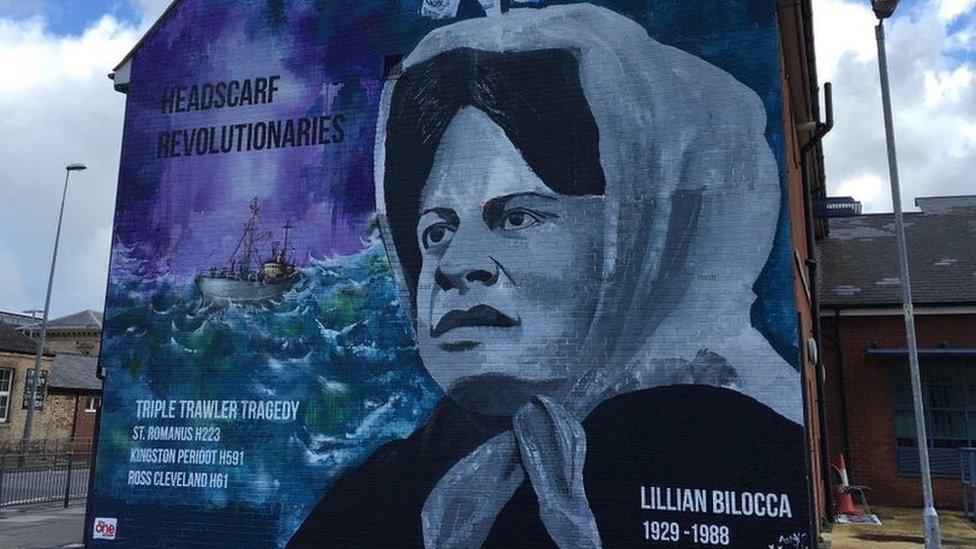

Hull's fishing heritage is remembered in murals on the city's Hessle Road and Anlaby Road

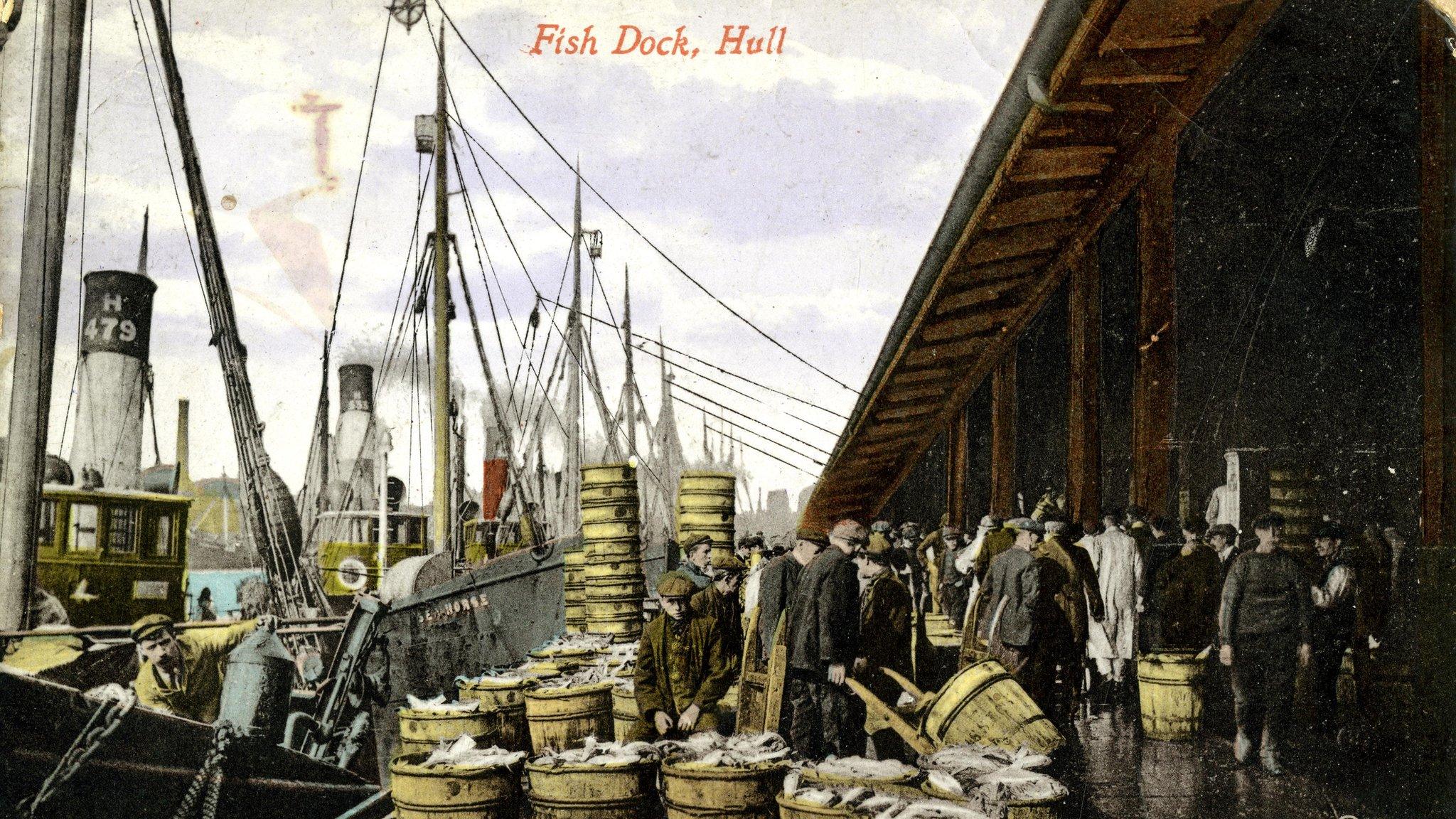

Fishing was an extraordinarily tough industry: it is estimated that more than 6,000 trawlermen from Hull alone perished between 1835 and 1980.

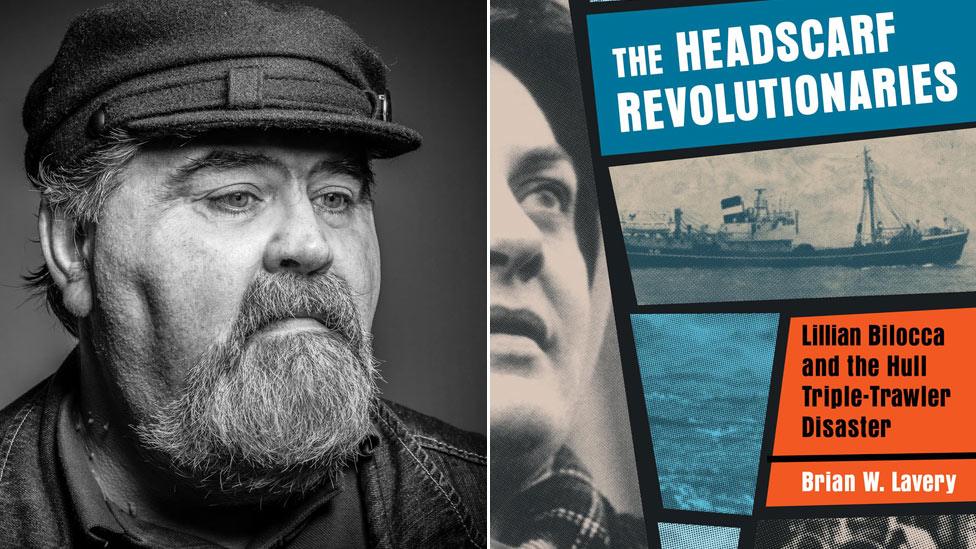

"Grief, and the commemoration of grief, was a constant for the city," said historian Brian W Lavery.

"It is often forgotten that fishing was a gigantic industry and the most dangerous on earth, worse even than coal-mining."

And although sorrow shrouded Hull at the start of 1968 - it was dubbed in one newspaper headline as "The Sad City" - fish still needed to be caught and life pressed on.

But in an era when health and safety practices were still rudimentary, nothing had been done to address some of the issues - chief among them the lack of full-time radio operators - that contributed to the tragedy. Led by the formidable Lillian Bilocca, it would be a group of four redoubtable women who would press for change.

"Big Lil" at the head of a demonstration after the disaster

Hull was at the time, according to Dr Lavery, the "greatest maritime city on Earth", and by necessity one that, on a day-to-day basis, relied enormously on the women who stayed ashore to keep it functioning.

"The men were away for about 20 days fishing and maybe then only back for three," the historian said.

"Despite the casual misogyny of the era many women told me: 'We were mother and father to our kids'."

Bilocca - "Big Lil" as she was nicknamed - embodied the can-do spirit of the women of Hull.

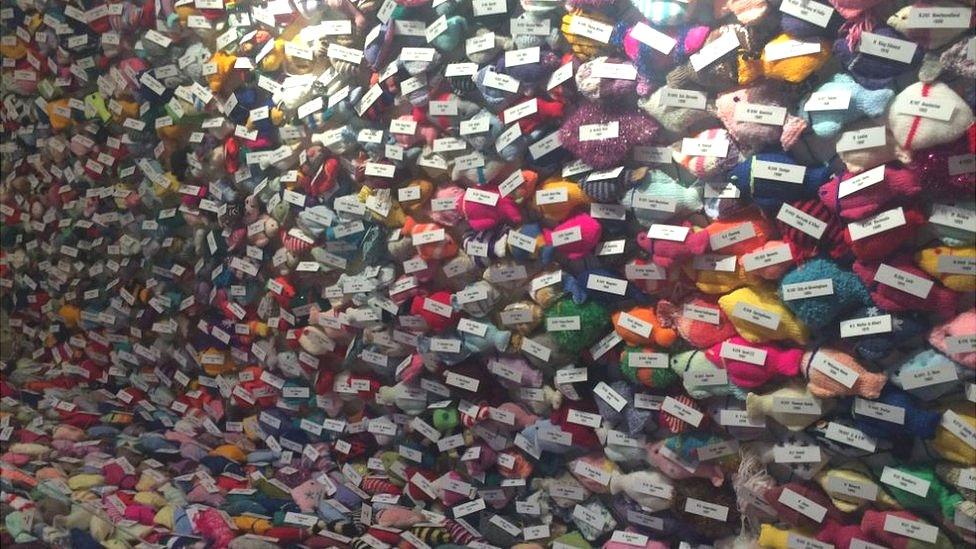

In the face of strong opposition, Bilocca, Christine Jensen, Mary Denness and Yvonne Blenkinsop - the four women dubbed the "Headscarf Revolutionaries" - are estimated to have saved thousands of lives through the safety campaign they fought.

A tribute to the lost trawlermen by the players of Hull FC, whose ground was near where the fishing community was based

"The group was not supported by all the men when they started their campaign," Dr Lavery said.

"Yvonne Blenkinsop was even punched in the face for getting involved in what some called 'none of their business'.

"It was ingrained: women didn't go on the dock, so much so that when Lil Bilocca led a women's march on to the dock, less than half of those following her would step on to it."

Nor was it easy for the crews themselves to formalise any changes to working practices.

"John Prescott said 'unionising trawlermen was like herding cats': after all you can't have a union meeting at sea," said Dr Lavery.

The attitudes of fishermen - perhaps today they would be described as macho - were also perhaps a barrier to changes to the industry.

As retired skipper Ken Knox said: "You took danger as a part of life - I was brought up into it from leaving school."

Did the rewards on offer to fishermen make the risk worthwhile?

Despite the hurdles placed in Big Lil's way - she even received death threats in the post - she would not be deterred from her goal.

Along with the other three women, she gathered a 10,000-signature petition calling for reform, leading a delegation to Parliament.

The women met ministers from the Board of Trade and the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries, and the Fisherman's Charter, which outlined the campaigners' demands, was presented to the trawler owners' association after a march on to the fish dock.

When the shipping minister made a statement in the Commons soon after the Ross Cleveland was lost, outlining a plan for government intervention in the trawling industry, years of campaigning by unions and MPs from Hull "had been trumped by seven days of campaigning by Lil and her headscarf army", according to Mr Lavery.

The sight of Lil Bilocca checking trawler safety became a familiar one on the dock

Among the measures the campaign won were safety checks before vessels left port, radio operators for all ships, improved safety equipment and a "mother ship" with medical facilities for all fleets.

Bilocca became a familiar sight on the dock, asking whether vessels had a full crew and a radio operator before waving them off. On one occasion she was restrained by police officers from throwing herself on to the deck of a trawler whose crew answered in the negative.

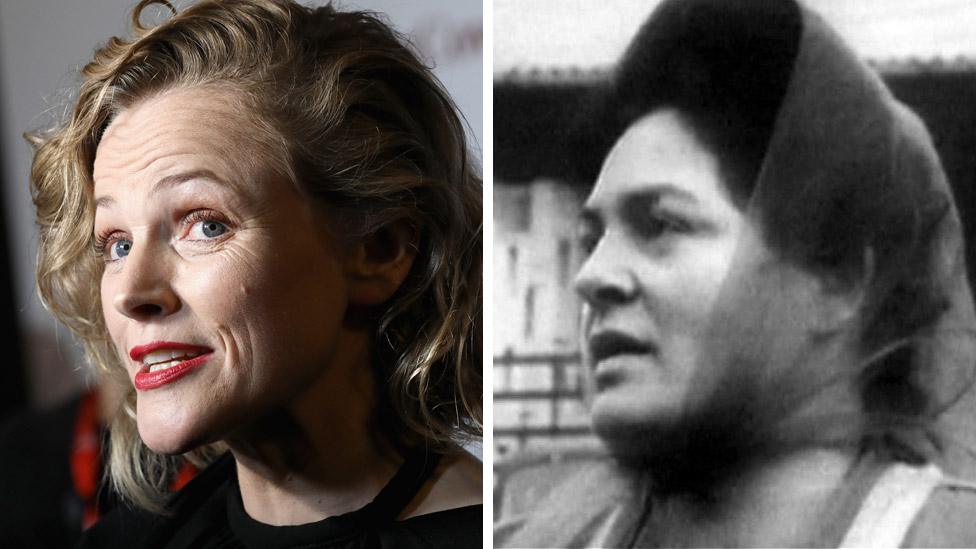

In November The Last Testament of Lillian Bilocca, a play about Big Lil's achievements by actor and playwright Maxine Peake, was premiered in Hull during its year as UK City of Culture.

"It felt an important story to tell," she told the BBC.

"It's about women putting their head above the parapet."

The Last Testament of Lillian Bilocca won praise from the critics

Hull playwright Val Holmes, who has also written about the life of Bilocca, said: "I think people are just realising what she did actually achieve."

But as it turned out, the tireless work of the Headscarf Revolutionaries made the lives of fishermen safer just as Hull was losing its status as a bustling fishing port.

"The four women saved thousands of lives with their actions but the irony was within a decade the industry was dead," Mr Lavery said.

A maritime city that relied on the wealth brought to shore by the "three-day millionaires" - a term coined to describe the short-term spoils enjoyed by the fishermen as a result of their weeks at sea - was already past its trawler heyday by 1968.

In 1970 Hull landed 197,000 tonnes of fish, but by 1981 that figure had fallen to only 15,000 tonnes, according to the Sea Fisheries Statistical Table.

Brian W Lavery coined the phrase Headscarf Revolutionaries to describe the campaigners

As maritime historian Robb Robinson points out, the world was changing and leaving Hull behind.

Key factors in the demise of the city as a fishing port were international economics and imposed fishing limits, according to Dr Robinson.

"Looking back, 1968 was a turning point internationally in so many ways; in Hull it was a watershed," he said.

"For Hull fishing, the decline amplified a time of change. It meant that many skills were cast to the wind.

"With the anniversary, the city is remembering a poignant loss, unnecessary deaths and also the loss of a way of life."

Hull's Headscarf Heroes will be on BBC Four on Monday 5 February at 21:00 and be available on the iPlayer shortly after broadcast.

- Published26 October 2017

- Published2 June 2017

- Published6 March 2017

- Published5 March 2016

- Published11 January 2016

- Published6 June 2015

- Published20 November 2013