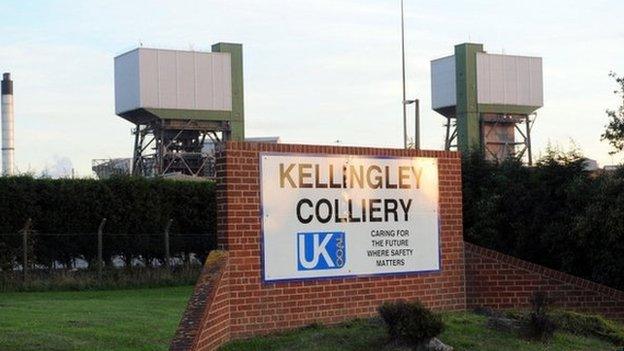

Kellingley miners remember life at UK's last deep pit

- Published

Kellingley Colliery miners talk about their way of life

As the UK's last deep mine prepared to close, BBC Look North's Danni Hewson spent the final months speaking to the men for whom Kellingley is home.

You hear them coming first. Often singing, always swearing, Kellingley's miners are a little nonplussed to find a woman waiting at the top of the lift shaft.

"Sorry love", a couple shout, obviously flustered.

The phased shut down of the pit, which began 18 months ago, has left them a much-depleted workforce.

Only 60 men on average spill out into the lamp room, hanging up safety equipment before marching to the showers where they scrub each other's backs. Their closeness is unmistakable and utterly disarming.

"It's camaraderie, like a family if you like. You spend eight or nine hours a day with a gang of men and you get close, trust each other, rely on each other. It's hard to explain really unless you've been in that environment."

Richard Allen drives the train that takes the men from the bottom of the shaft to begin the five-mile journey to the coal face.

Kellingley still has vast reserves in the ground but could not compete in the face of cheaper imports, lack of investment, increases in carbon tax on generating electricity from coal and the switch to green energy

He came to Kellingley in 1985 following the miners' strike and the idea of finding work away from the familiarity of the pit is concerning.

"I've tried not to think about it," he said.

"I'm going to have to after Christmas because I'm not 50 yet, so I'll have to find other employment. But like I say, I've done this for 30 years so it's going be hard."

Asked what he might like to do, his answer gives an insight into the life he has led.

"Somewhere I could work outside, in fresh air, somewhere I don't have to do shifts. I've no skills other than what you use underground, driving loads of machinery but machinery you'll never see on surface."

Whether or not their skills are transferable is a common concern.

Now a grandfather, Carl Jarret has started over many times, hopping from dying pit to dying pit.

"The mines were closing in Wales so I moved up, brought the family with me and I never looked back until now. Sad times."

The average age of the men at Kellingley is 51, with many joining the pit straight from school

Like many miners, he assumed Big K's vast reserves would guarantee its survival for at least another 10 years.

"It's unbelievable what's happened to the coal industry, the demise has been very quick and it's been a big shock to us all.

"We've all now moved to the last mine and we are the last of the people, the last of the miners, and if we ever do go back into coal 10 years down the line we'll have no people to do it.

"UK Coal has put a lot of money into training us. That's why we are what I consider the safest and best miners in the world."

During my first visits to the colliery, anger and bitterness were the overriding emotions. Now there is an acceptance and quiet dignity.

Nigel Kemp has worked at Kellingley all his life, following his father who sunk the shafts in 1958.

"Shake a few hands and walk out of the gates and that's it."

An employee buyout deal to save Kellingley Colliery was scrapped in July

The miner talks about his job like a marriage - it is simply part of who he is and he's realistic about what his future may hold.

"I'm going to find it very difficult to get another job when I leave because I've never been for an interview in my life. I came here and, basically, when we started if you could fill a form in or read the paper you got set on."

But push him a little and anger shimmers under the surface.

"I do think we've been a bit hard done by by the government. There's 60 million tonnes of reserves and I think we should have been given a chance and some state aid to get the reserves out to keep the power for the country because they're not going to stop burning coal, it just won't be Kellingley coal."

- Published18 December 2015

- Published18 December 2015

- Published18 December 2015

- Published10 December 2015

- Published23 July 2014

- Published10 April 2014