Kellingley mining machines buried in last deep pit

- Published

Seventeen miners have lost their lives at Kellingley since it began production in 1965

The UK's last deep-pit coal mine is closing and buried in its cavernous darkness will be tens of millions of pounds of advanced mining machinery, which is now effectively worthless. What happens when you wind up a pit that helped power the nation?

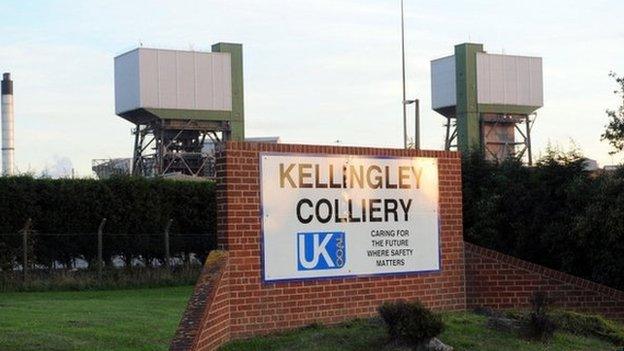

Dubbed the "Big K", Kellingley Colliery in North Yorkshire is a sprawling 58-hectare site of equipment synonymous with an industry that has seen both great fortunes and devastating conflict.

Its two winding towers, emblazoned with the letter K, stand connected to a web of conveyor belts and processing sheds surrounded by vast expanses of muck heaps.

At its height it employed about 2,000 people and was the biggest deep mine in Europe, at one point bringing 900 tonnes of coal an hour to the surface.

Two shafts descend some 800m (2,600ft) underground where, from the bottom, miners travel about five miles on small battery-powered trains in 30C heat and humidity before laying chest down on a conveyor belt to reach the coal face.

After the pit's closure, one of the main jobs will be sealing the shafts, underneath which, in the labyrinth tunnels, will be the now redundant mining equipment worth some £150m.

The average coalface is between 300m and 350m in length and produces up to 2,000 tonnes of coal per cut

The machinery includes the giant underground shearer which cuts coal from the face, supports weighing up to 30 tonnes, the train ridden by miners and the huge gears used to drive the conveyor belt.

Kellingley Colliery manager Shaun McLoughlin said investment at the site over the years had gone into state-of-the-art equipment, but because of wider pit closures there was no demand for it.

"It will just be sealed in the underground. It cost too much to salvage it and there's no market for it even if we did salvage it.

"We have got some good mining machinery on the surface that we have tried selling all year round and we just can't sell it, so that's going in the scrap bin for scrap value."

In the days when more deep mines were operating across the country, equipment was often sold on to other sites for the cost of removing it.

But Andy Smith, director of the National Coal Mining Museum, said UK Coal, which owns Kellingley, had been forced into a different situation.

The former miner, who has has worked at several Yorkshire collieries, said: "It's almost criminal really, but there's no other choice.

"To keep a mine going there are massive fixed costs. There's the costs of inspecting the shafts and the infrastructure alone, so basically as soon as they cease production which is paying for it all, the quicker they can get it shut.

"Although you're looking at a lot of money, you're looking at a bigger amount of money to keep it running."

Along with some 20 workers from Kellingley, Mr McLoughlin, who started at Kellingley as a general worker in 1977, will remain on site over the coming months to make it safe.

So much coal has been extracted since Kellingley opened that from the bottom of the shafts miners travel six miles on trains and then conveyor belts

The shafts will be emptied of cables and ropes and then filled with a concrete block about 10 metres deep.

Demolition then starts on the surface buildings and the site will be levelled out before ownership is transferred to Haworth Estates for future redevelopment.

What that will be is unknown, although the company said it would be focused on replacing jobs lost by the closure.

For now Mr McLoughlin will remain at Kellingley steering the pit to its end.

He said: "In some respects it's very sad but in other respects I feel very privileged to be the last manager here and to be at the last deep mine in the UK."

- Published10 December 2015

- Published23 July 2014

- Published19 August 2015

- Published10 April 2014