Princess Alice disaster: The Thames' 650 forgotten dead

- Published

The sinking of the Princess Alice remains Britain's most deadly inland waterway accident

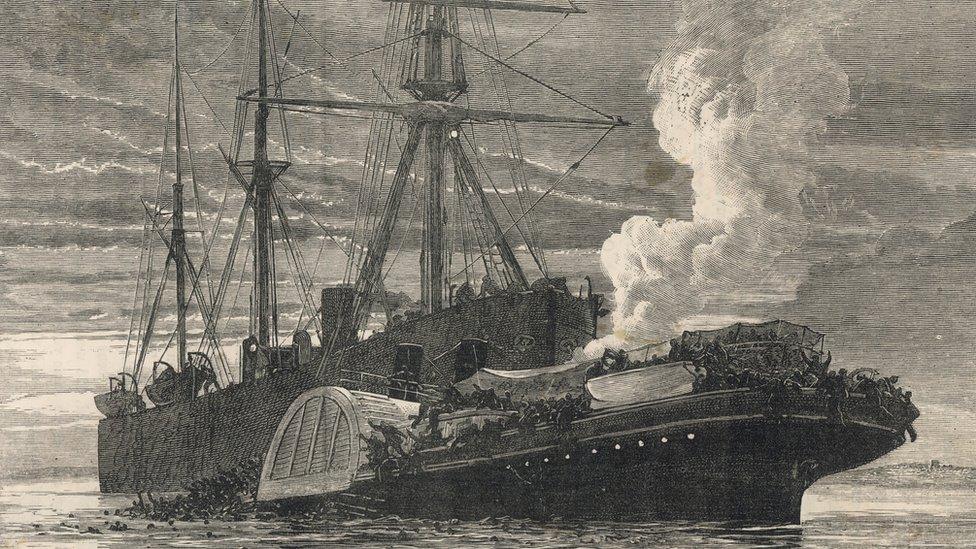

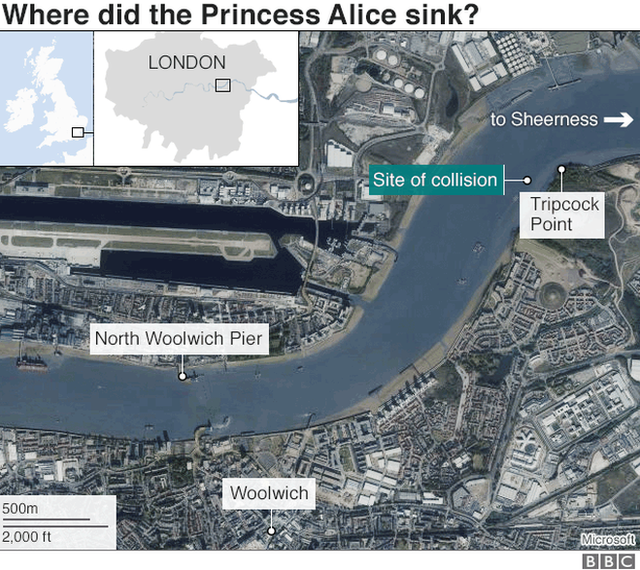

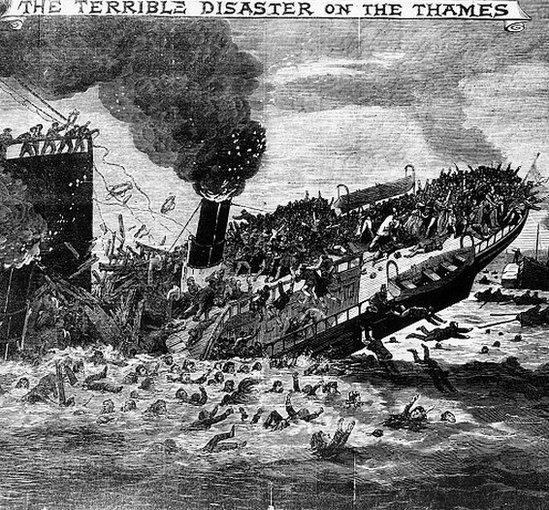

The Princess Alice sank in the River Thames on 3 September 1878, killing hundreds of ordinary Londoners returning home from a day trip to the seaside. The tragedy, now largely forgotten, dominated newspaper headlines and led to changes to the shipping industry.

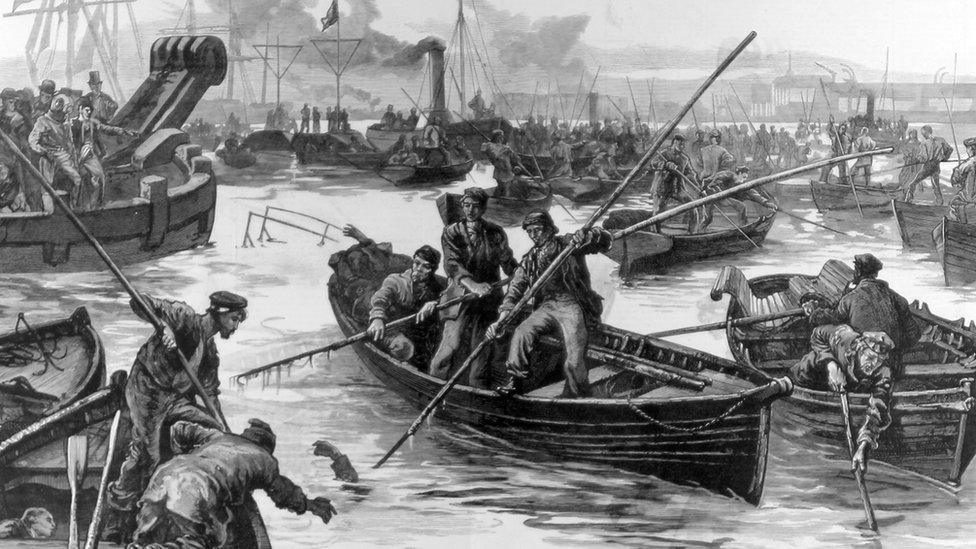

A boatman hooks another body out of the foul-smelling Thames, a grisly prize that will earn him five shillings.

A few days before, the Princess Alice had been smashed in two as it returned to London packed with men, women and children who had been on a trip to Kent.

About 650 lives were lost and for weeks bodies decayed in the polluted water or washed up on the riverbank.

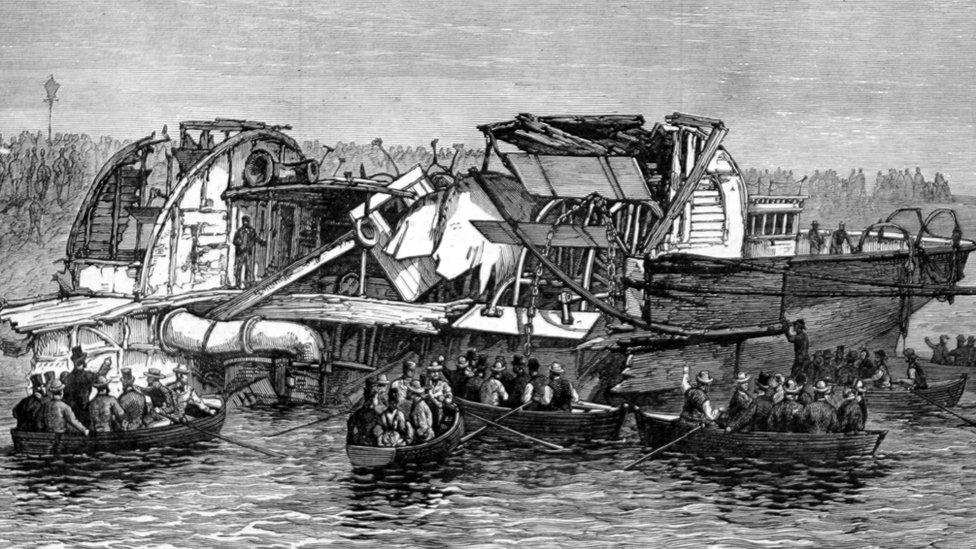

This model shows how the Princess Alice was sliced in two, its ends rising out of the water and sending passengers hurtling into the murky river

On the morning of the disaster, the weather was bright and the passengers were excited as the pleasure steamer set off from London and headed out to catch the end of the summer sun and the fresh sea air of Sheerness.

It was an inexpensive trip - tickets were about two shillings, depending on which stop passengers travelled to.

Most of the approximately 700 people on board were upper working-class or lower middle-class families.

The children were tired but happy after their day at the famous Rosherville Pleasure Gardens in Northfleet, playing on the promenade at Sheerness or wandering around the popular resort of Gravesend.

As the evening drew in, many families took the decision to retreat inside the saloon or to their cabins below.

It was a move that sealed their fates.

Alfred Thomas Merryman, who survived the sinking, described the panic on board the ship

Alfred Thomas Merryman, a chef, had been asked at the last minute to work on the ship.

The 30-year-old father of four from Bow, east London, was no doubt grateful for the extra cash, as well as the rare opportunity to escape the dirty streets of the capital.

At about 7:40pm, as the Princess Alice neared North Woolwich Pier, he was standing on the deck by the saloon door.

Just as he was saying how "splendid" the voyage had been, he saw a huge collier (a coal-carrying ship) bearing down on the smaller vessel.

The Princess Alice sank within minutes of the two ships colliding near Woolwich, south-east London

Princess Alice disaster: Dead forgotten 'for being working class'

The Bywell Castle ploughed straight into the starboard side of the Princess Alice, which weighed less than a third of the 890-ton collier.

The vessel sliced the Princess Alice in two with a sickening crash.

"The panic on board was terrible, the women and children screaming and rushing to the bridge for safety," Merryman's witness account reads.

"I at once rushed to the captain and asked what was to be done and he exclaimed: 'We are sinking fast, do your best.'

"Those were the last words he said. At that moment, down she went."

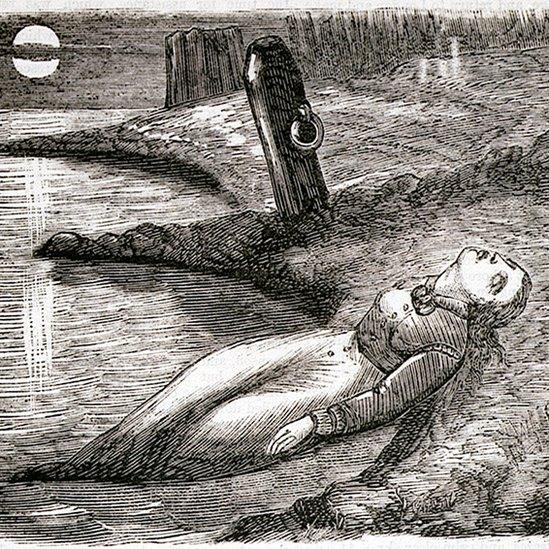

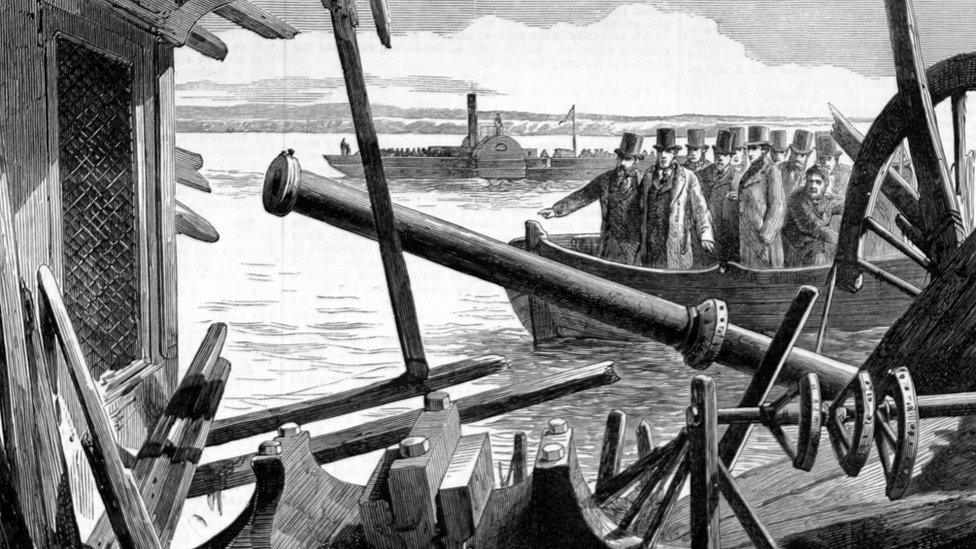

This illustration, entitled 'How They Found My Poor Girl', depicts one of the stream of dead who washed up on the shores of the Thames after the collision

As a model held by the National Maritime Museum shows, the ends of the ship rose into the air as the middle sank, sending people on deck hurtling into the watery chasm between.

Merryman and others on deck were pitched into the churning river, while the unfortunate passengers below deck were trapped.

Tons of untreated sewage spewed from outlets near where the boats collided.

The water bubbled with raw detritus, giving out a stench strong enough to leave even the hardiest boatman gagging.

Boatmen used large hooks to retrieve bodies from the water

The men, women and children thrashing about in the water breathed in lungfuls of toxic waste.

Despite crew members of the Bywell Castle throwing down planks of wood, lifebuoys and even chicken coops for people to cling to, the heavy Victorian clothes of those in the water dragged them down. For many, death was inevitable.

Deafened by the screams of his doomed fellow passengers, Merryman clung to a piece of wreckage to stay afloat.

But when about 20 desperate people grabbed hold too, it sank.

He started swimming - one of the lucky few who could - and lunged for a rope hanging over the side of the Bywell Castle. He was hauled to safety along with four others.

The Princess Alice had just rounded Tripcock Point on its way back to Woolwich when it collided with the Bywell Castle

Other survivors described being overwhelmed by an instinct for survival.

One man told the Illustrated Police News - a somewhat sensationalist tabloid - how he had to push drowning people off him to reach safety.

Claude Hamilton Wiele said: "I found my brother swimming about. We are both good swimmers, and we made for the screw steamer."

The 20-year-old clerk added: "The water was full of people... we had great difficulty in avoiding them.

"A woman clutched me, but I got away, and I saw her go down like a stone."

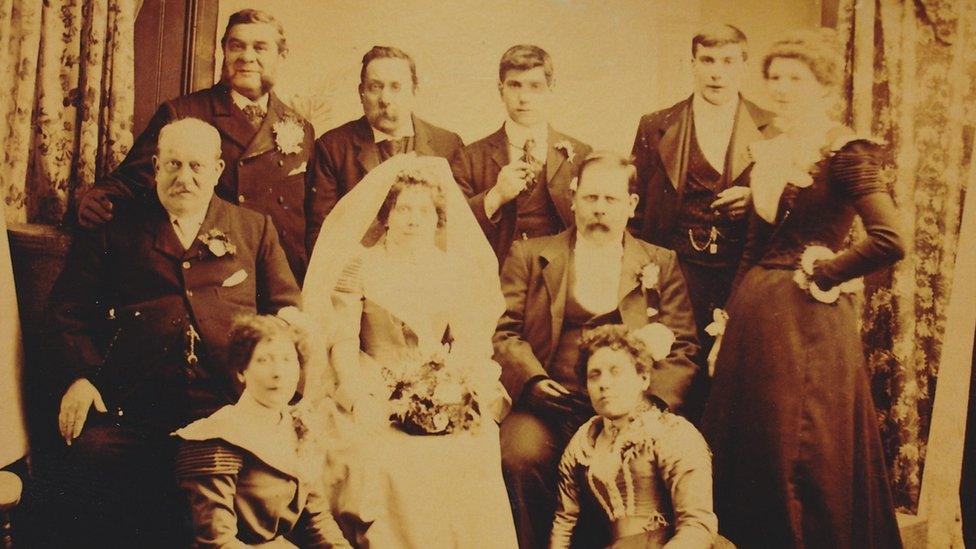

Merryman was one of about 100 passengers on the Princess Alice who survived. He is pictured here in his eldest son's wedding photo, second from the left on the back row

The wreck of the Princess Alice was examined as part of the inquest

Merryman was taken to South Woolwich Pier after he was retrieved from the water.

"There were others also rescued but few recovered," he said.

"One boy died on my lap."

You might also like:

The chef was one of about 130 people pulled from the river alive - several of whom died in the following days and weeks, in part from complications from swallowing the putrid water, The Times reported.

Robert Haines, a musician in the Princess Alice band, was also saved.

The double bass player was fond of ships and had noticed the Bywell Castle a couple of minutes before the collision.

The inquest jury of 19 men spent weeks examining evidence

It looked to him as though the collier was heading straight for the smaller boat but he thought little of it, having faith the Bywell Castle would alter its path.

The musician was about to follow his fellow band members downstairs for a break.

He was only about 3ft from the bow of the Bywell Castle when it struck.

For a split second, Haines was frozen in his tracks, not knowing what to do with his bulky instrument.

But he then dropped the double bass and ran up on to the saloon deck.

"In one instant I might say, the fore part severed from the stern and I saw them all go down like a band box," he said.

"Everybody went down except myself."

One survivor described how he pushed a drowning woman away from him so that he could swim to safety

Haines could not swim, but managed to grab hold of a lifebuoy. He was pulled on to a boat that had been launched from the Bywell Castle.

The men on board dragged a few more survivors from the water - as well as dead bodies - before rowing to safety.

Other small boats on the river came to the aid of drowning passengers, but the rescue mission soon became a morbid effort to recover as many bodies as possible.

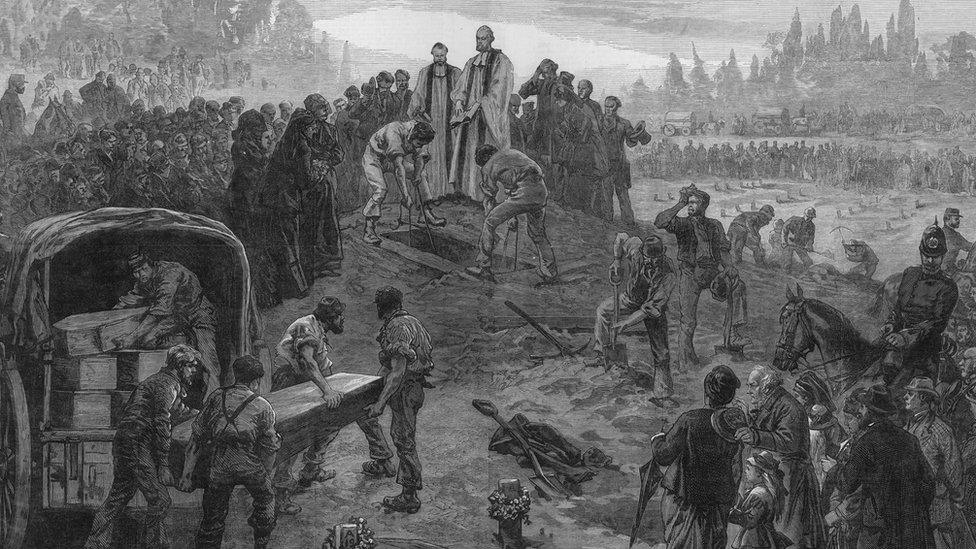

In a matter of minutes children had been orphaned, husbands and wives widowed, and whole families wiped out.

Bodies washed up from Limehouse to Erith for days after the crash.

The dead were laid down in their hundreds in temporary mortuaries that popped up across east London - including at Beckton Gas Works, Woolwich Dockyard, the office of the London Steamboat Company and Woolwich Town Hall.

At Woolwich Cemetery, 120 unidentified victims were buried in rows

As the terrible shock of the tragedy turned to anger, bereaved family members and local politicians demanded answers.

Why did the ships collide? Who was to blame? Was the Princess Alice overcrowded? Why were more people not saved by lifeboats? Is sewage deadly? Was it true that the captain of the Bywell Castle was drunk?

The day after the disaster, coroner Charles Carttar opened an inquest, while the Board of Trade launched a separate inquiry a few weeks later.

For two gruelling weeks, all the inquest jury could do was observe as a steady stream of bodies and thousands of worried family members filled the streets of Woolwich, gazing at the corpses with feelings of both dread and hope as they searched for a face they recognised.

The coroner eventually accepted that because there was no passenger list, the exact number of people on board the ship, and therefore a precise death toll, would never be known.

A memorial at Woolwich Cemetery, by the burial site of the unidentified dead, was paid for by donations from more than 23,000 people

Over the next two months, the 19 men on the jury heard hours of evidence, the written version of which was about 5,000 pages long.

On 13 November, the coroner shut them in a room and refused to let them leave without returning a verdict.

At one point, a Times correspondent said 11 jury members wanted to bring a manslaughter charge for the lives lost against those in charge of the Bywell Castle, but 12 votes were needed for a verdict to be accepted.

The next morning, the men had finally made up their minds.

Their main findings were:

The Bywell Castle should have stopped and reversed its engines earlier

The Princess Alice should have stopped and should not have turned astern

All ships on the Thames would avoid collisions if more stringent navigation rules were enforced

The Princess Alice was seaworthy at the time of the crash, but was not sufficiently manned, had more passengers on board than "was prudent" and had insufficient life-saving equipment

However, the simultaneous Board of Trade inquiry came to different conclusions - despite many of the same witnesses giving evidence.

Instead of arguing that both vessels were to blame, it postulated that the Princess Alice had not followed waterway regulations and was entirely at fault.

Concerns were raised in Parliament for years after the disaster to ensure that positive change came out of the tragedy.

From who was responsible for paying for the burials of identified people, to how to clean up the river, Londoners were impassioned about what kind of legacy the sinking would have.

Improvements to the sewage system, the adoption of emergency signalling lights on boats across the globe and the new Royal Albert Dock, which helped to separate heavy goods traffic from the smaller boats, all came as a result of what happened.

Tripcock Point sits on a bleak and mainly industrial stretch of the Thames

Despite the huge loss of life and changes brought about as a result of the sinking of the Princess Alice, today there are few clues as to what happened on that fateful evening.

The bank near where the steamer met its end is quiet; the silence occasionally broken by gulls cawing as they wheel through the sky, and the grating clang of machinery from the scrap yards in Barking.

A memorial plaque was unveiled in Creekmouth after a community group secured a National Lottery grant, external in 2008.

Across the river, the only reminder at Tripcock Point, close to where the tragedy happened, is a faded and graffiti-marked information board.

The sole, sorry-looking marker of the disaster at Tripcock Point

Thanks to Joan Lock, author of The Princess Alice Disaster, for her help with this article.

- Published13 June 2015

- Published20 August 2014

- Published12 April 2012

- Published14 January 2012