Janice Nix: The drugs kingpin who joined the Probation Service

- Published

Janice Nix led a life of crime in the 1970s and '80s and spent more than 17 years in prison

Janice Nix used to be a notorious London drug dealer. Known as Mamma J, she drove flash cars and had money to burn.

Her crimes caught up with her though and she spent many years in prison. The suicide of a fellow inmate would lead to Janice to turning her life around, and she went on to become a probation officer.

The 62-year-old, who has released a memoir about her eventful life, has now left the Probation Service but still works voluntarily to help vulnerable women in the capital.

She describes her transformation from drug dealer into Probation Service engagement officer as at one point being "the most talked about thing on Brixton High Road".

People who remembered her dealing and driving fast cars were speechless to meet her again when they walked through the doors of Brixton police station.

Sometimes her past still makes her uncomfortable.

"I am not proud about it," Janice says. "Sometimes I cringe when I think about my criminal history but then I am gentle with myself, because I also understand that without that past I couldn't have what I have in front of me today - [the chance] to teach people, to support women."

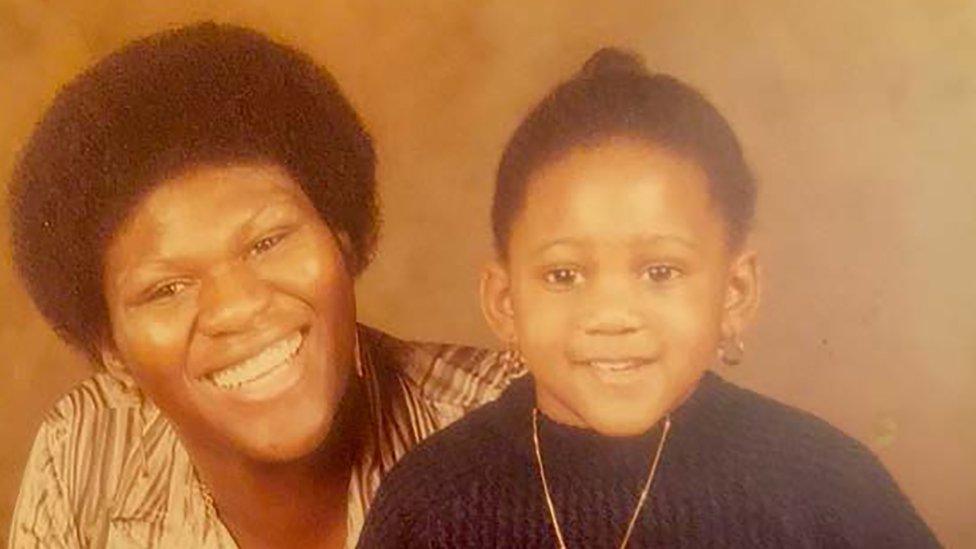

Janice with her daughter Nadia in 1982

She had started out as a shoplifter in the mid-70s, stealing furs from Harrods and dipping into the bags of wealthy shoppers in London's West End.

In the evenings Janice would return home to her sleeping toddler Nadia, who soon learnt to count her mother's earnings and had excuses ready when the police called.

By the 1980s Janice was firmly established as a drug dealer. By the 1990s she was serving a long prison sentence.

Janice had her first legitimate job at Woking Community Hospital

In the 15 years since her release, Janice has worked as a ward clerk in a hospital and supported ex-offenders through the St Giles Trust.

She joined the Probation Service just before the decision in 2014 to part-privatise it.

She describes the policy - since reversed - as "a bad idea", and one that eventually saw her spend more time behind a desk instead of having face-to-face meetings with offenders.

The women she worked to help were often not there through choice, but to avoid custodial sentences, and Janice talks about them with affection.

She says they faced the same problems she did, the same problems so many young women face today: a lack of role models and a sense of isolation magnified by poverty.

Janice Nix, pictured here with her then colleague Emma Parton. left the Probation Service in 2018

Aged 62 she is busier than ever, supporting women struggling to survive under the government's lockdown restrictions.

Janice is used to hearing about troubled lives damaged by domestic abuse, drugs and violence. She thinks the strain put on women by the coronavirus pandemic hasn't been fully appreciated.

"I've had one lady that's locked off completely; I had to go there because her mental health was that bad I felt she would have harmed herself," she says.

Janice says she worries about the single mums the most, cooped up in high-rise flats with young children, struggling to put food on the table.

The idea that someone might injure themselves because she had not done enough to help is something that haunts Janice from her time in prison.

It was there she spent hours trying to console another inmate, a desperate mother whose children were being taken into care.

The woman killed herself the following day.

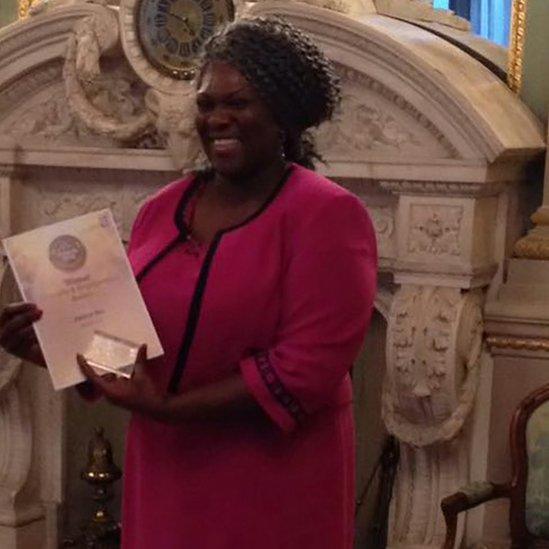

In 2016, Janice received a Diversity and Engagement Award for her work as a probation officer

Janice's father had come to England in 1957, and her mother followed. They set up home in west London. Amid the ever-present atmosphere of racism, Janice remembers sleeping under the bed because her father feared teddy boys in Notting Hill would identify their curtains as those of a black family and throw a petrol bomb through the window.

He was desperate for her and her brother to get a good education, enrolling them in violin and piano lessons, but she says feelings weren't discussed in their home.

When her parents split up, Janice lived in Antigua and then Leicester with her mother before running away to London, where her crimes caused her to become estranged from her family.

Now reconciled with her daughter Nadia, Janice has dedicated her memoir, Breaking Out, to her.

Janice hopes the book will find its way to people looking for help, as well as those curious about her gangster past. Her great sadness is that her father, who died in December, will not see it published.

She cries as she talks about him, the man who once lambasted her for becoming "a blasted thief and drug dealer".

He had refused to visit her during her last prison sentence, but Janice takes comfort in their final parting, saying "his eyes and tears told me he forgave me".