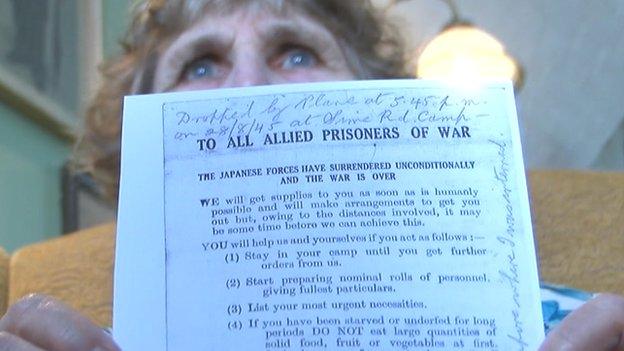

'I celebrated my 10th birthday in Changi PoW camp'

- Published

Olga inspected the quilt she made in 1943 with her fellow child prisoners

The life of a prisoner in a Japanese World War Two camp was a meagre existence, but children in Singapore's notorious Changi prison managed to eke out a semblance of childhood.

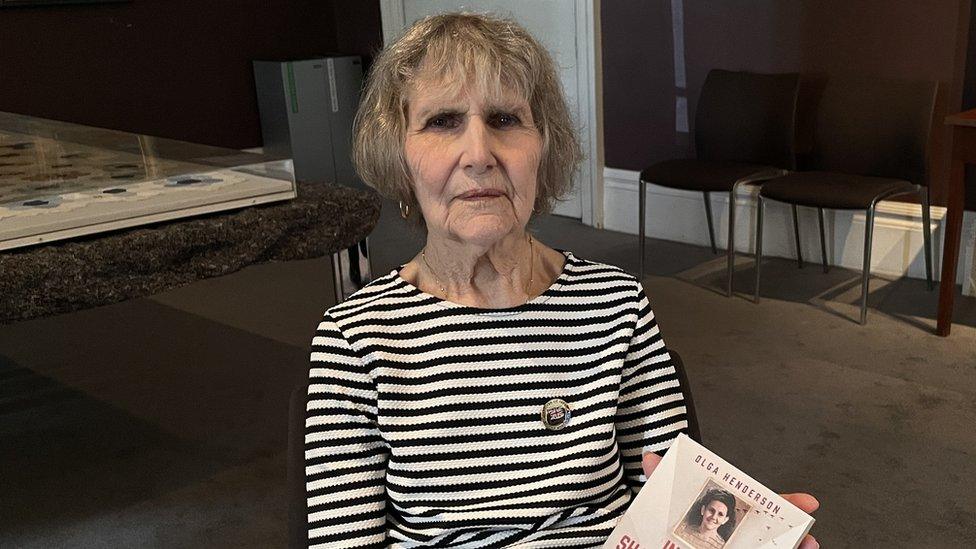

One of those was Olga Henderson, 91, who has been reunited with a quilt she made with her fellow child prisoners.

She was a guest at London's Imperial War Museum, where it is archived.

Mrs Henderson, now an Eastbourne resident, said she was proud to see it to mark VJ Day on Tuesday.

"It really was looking rather tatty when it was sent here," she said. "It's [now] so polished and looked after. I can't believe it."

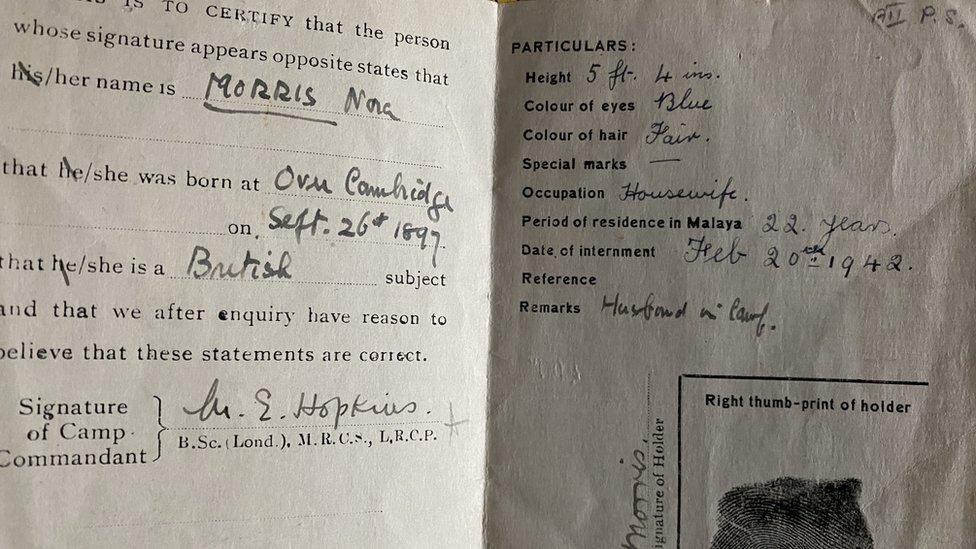

In February 1942, Mrs Henderson lived in Johor Bahru, in British Malaya (modern day Malaysia), with her parents and three siblings when, along with Singapore, it was invaded by the Japanese.

A British Army officer arrived at the family's home to inform them that Japanese soldiers were 10 miles away and they were evacuated onto the island of Singapore.

The family lived in British Malaya, now Malaysia, in the years up to World War Two

However, the island refuge did not last for long as days later British forces there surrendered to Japan.

Nine-year-old Olga Morris - as she was then known - and her family were forced to walk 17 miles without water to the centre of Singapore, then on to Changi and three years in captivity.

While the horrors of Changi were unrelenting, with forced labour, food shortages and inhumane living conditions, the adults tried to establish some sense of normality for the children.

Mrs Henderson told the BBC that one of the adults, Mrs Ennis, had established a Guides group, which had to be kept secret from Japanese guards.

"I don't know how she got away with it," she added.

ID card for Nora Morris issued by Japanese occupiers

The children found space in the likes of the camp's carpenter shop to put on plays.

On Mrs Henderson's 10th birthday, she described how a woman called Mrs Mulvaney managed to get her a piece of blue satin for her dress and fashion a petticoat out of a rice bag.

"Everybody donated a bit of their cooked rice so we made a cake," she recalled.

Olga Henderson, 91, spent part of her childhood in a Japanese prisoner of war camp

Asked what kept her and her family going through their time as inmates, Mrs Henderson said: "We had so much work to do."

Her mother cooked rice for the Japanese soldiers, while Mrs Henderson worked in the match factory and later dug trenches, she said.

Maria Castrillo, from the Imperial War Museum, said: "My job involves connecting people with collections.

"Having this [quilt] is hugely significant. It is an object of huge cultural significance because it was made in very difficult conditions by young people, and it really shows the impact of war and conflict on younger people."

Follow BBC London on Facebook, external, Twitter , externaland Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to hellobbclondon@bbc.co.uk, external

Related topics

- Published15 August 2015