Golborne mining disaster: 'Why was I the only one to survive?'

- Published

Brian Rawsthorne was the only person to survive the explosion

Apprentice electrician Brian Rawsthorne was one of 11 men working deep under the ground in Golborne Colliery's Plodder Seam on 18 March 1979.

The 20-year-old would be the only one of them to live to tell the story of that Sunday shift.

When a build-up of methane in the mine, near Wigan, exploded, it sent a fireball 600ft (182m) up a tunnel.

Brian woke up to find himself bent double over a pipe, having lost his shoes, socks and belt in the blast.

The man with whom Brian was working was killed.

"You tell me why he died, and I didn't?" Brian, now 65, asks, still unable to comprehend how he became the only survivor.

Miner Neal Rigby was one of the first on the scene after the explosion

Neal Rigby, who was also working underground at the colliery, was one of the first on the scene and helped carry Brian to the surface on a stretcher.

"I don't think I was a hero: I was just looking after my mates at the pit," says Neil, now 71.

"In all my life as a pitman, I never had to deal with people like I dealt with them lads.

"Giving mouth to mouth, injecting them, hoping they'd live... and then they didn't."

Hundreds of people worked at the mine run by the National Coal Board

The colliery opened in 1880, and at the time of the explosion about 870 men worked at the site, scooping more than 9,000 tonnes a week from its seams.

On the day of the disaster, Brian was with 10 other men, aged between 23 and 45, who were working in the Plodder Seam, about 1800ft (548m) below ground.

At about 11:15 the explosion tore through the tunnel, killing three of the men.

The other seven would die later in hospital.

It was not long before news of the explosion reached the surface.

Angela Berry heard news of the blast on the radio at her home in Leigh. Her thoughts turned to her 41-year-old dad, John, who worked in the mine.

When she saw a union representative walking solemnly up the garden path, she knew the worst had happened.

"He just shook his head", she says, remembering how her mother collapsed in shock at the news.

"And I just knew from that minute that nothing would ever be the same again."

Brian Rawsthorne with his wife Jane

For several weeks after the tragedy, Brian lay in Withington hospital in Manchester, recovering from his burns.

One of his nurses, Jane Whitworth, would later become Jane Rawsthorne.

"He told me he loved me, and he asked me out," she says. "I said to him, 'When you're not under the influence of an anaesthetic, ask me again'."

Brian persisted, "So I went out with him and it blossomed from there," she says.

Those who died at the mine are remembered on a memorial stone in Golborne

Today, the shadow of the disaster still looms large in the memory.

A memorial stone stands on Kid Glove Road, and this year's annual remembrance service at St Thomas' Church will mark the 45th anniversary of the tragedy at the mine, which closed in 1989.

For those whose lives were touched by the disaster, it is important that the men who died - John Berry, Colin Dallimore, Desmond Edwards, Patrick Grainey, Peter Grainey, Raymond Hill, John McKenna, Walter McPherson, Brian Sherman and Bernard Trumble - are not forgotten.

Angela says it is "extremely important" that people - especially young people - understand the work these men and others like them did, and "how hard the jobs were".

"They lay down for eight hours a day digging coal, it was damp, it was dark, it was dusty.

"There's not an industry now where you would put up with that.

"That the men looked after each other is important to remember as well.

"I'm massively proud of my dad, a hard-working man."

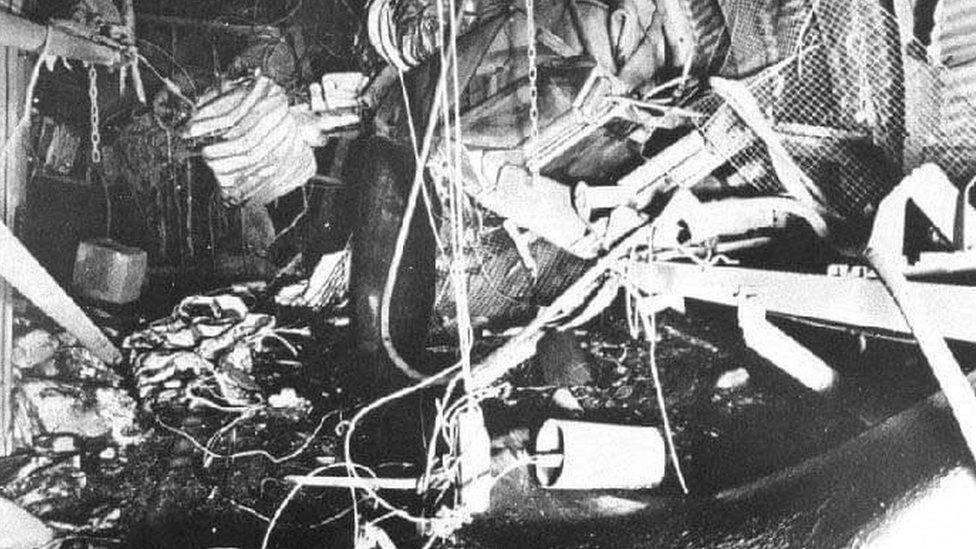

The aftermath of the explosion at the Golborne colliery

Six recommendations followed the inquiry into the disaster, including improvements to underground ventilation and new rules on the testing of electrical equipment in mines.

"I should hold a grudge against people, but I don't," says Brian, who as a member of the Golborne Ex-miners Association visits schools to tell the story of the explosion and the history of mining.

"Ten people died. I could have been number 11, but I wasn't.

"It's important that young people never forget what happened."

Why not follow BBC Manchester on Facebook, external, X, external and Instagram, external? You can also send story ideas to northwest.newsonline@bbc.co.uk