Immunotherapy: Mum responding to cancer 'experiment'

- Published

Liz Sheppard is raising money for her treatment through crowdfunding

A mother-of-three who was given just months to live is responding to cancer treatment after paying privately to "experiment" on herself.

Through fundraising, Liz Sheppard has paid for a relatively new treatment called immunotherapy, which has been described as a "game-changer".

The NHS has not approved its use for treating the very rare type of cancer 36-year-old Mrs Sheppard has.

But a "golf ball-sized" tumour on her neck has already shrunk.

Her medical team may write up her case in a journal, saying it could influence the way other patients are treated.

However, Mrs Sheppard is running out of money for the treatment and is trying to raise more through crowdfunding.

"The treatment has never been tested for my type of cancer, so essentially I've paid to experiment on myself," she said.

"I had a huge tumour on my neck that was like a golf ball sticking out, but I got up one morning and the tumour had just gone.

"I've had a fantastic response to it but the money is running out, and it's a life or death situation."

What is immunotherapy?

James Gallagher, BBC health and science reporter

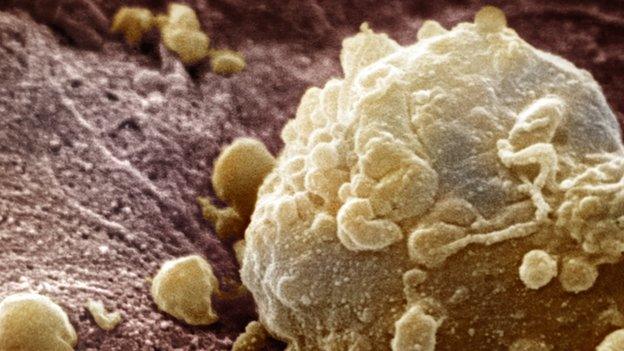

Immunotherapy uses the body's own immune system to fight off cancer.

Our immune system is like a police force, protecting us from diseases.

Normally our immune system spots and destroys faulty cells - like cancer ones - but sometimes these can escape detection and develop into tumours.

Instead of targeting the cancer cells themselves, as many traditional cancer drugs do, immunotherapy reawakens the immune system so it can "remember" the cancer and stop it in its tracks.

A number of immunotherapy treatments are already showing considerable promise.

Mrs Sheppard, who lives in Nottinghamshire, was diagnosed with small cell gastric cancer - a very rare and aggressive type - in November 2015.

She said her first thoughts were for her young daughters, who were aged three, eight and 14 at the time.

She had chemotherapy and radiotherapy on the NHS but started researching other options when she became increasingly ill.

She is now being treated by Leaders in Oncology Care (the LOC), a specialist cancer treatment centre in London.

Before and after immunotherapy

The visible tumour on her neck has shrunk and her quality of life has improved

Jane Lynch, senior lung clinical nurse specialist and respiratory service lead, said Mrs Sheppard was "weeks or short months" away from death when she came to the LOC in October.

"You could see the tumour was growing on her neck and she was really unwell with it; she could barely get out of the chair," said Ms Lynch.

"She was unable to look after her children and she needed help with everyday life.

"She was tearful and she was ready to pack it all in, she felt so unwell. She had no quality of life.

"She had nothing to lose and everything to gain."

She is being treated by Professor Justin Stebbing and has had six courses of the immunotherapy drug - called nivolumab - so far, costing approximately £5,000 to £6,000 every two weeks.

"The difference since she's been on immunotherapy, there's no comparison," said Ms Lynch.

"She has gained energy and the last time I saw her she was like a little firebomb; she could talk for England.

"There is no doubt in our minds that the immunotherapy has had a good clinical effect."

Liz Sheppard was given a terminal diagnosis last year, 17 days before her daughter Olivia was christened in August

Small cell cancer is usually associated with the lungs, and it is very rare to have small cell gastric cancer, like Mrs Sheppard has.

"She's a complete anomaly because we've never treated a gastric small cell cancer patient with immunotherapy before," said Ms Lynch.

"We would consider writing up her case in a medical journal if there is a continued response.

"What goes on here could change our view of how we think of immunotherapy for other unusual or rare cancers."

Liz Sheppard needs to raise more money, as the treatment costs approximately £5,000 to £6,000 every two weeks

However, she stressed not all cancer patients would respond to the drug and it was not a miracle cure.

"We haven't got enough data to say immunotherapy is a cure; we are saying it's a long-term control for certain diseases," she said.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (Nice) issues guidance on whether people should have automatic right to a treatment their doctor says they need.

It has recommended nivolumab for use in some types of cancer, but said it had not been asked to look at nivolumab for small cell gastric cancer.

"Before we issue final guidance local bodies make their own decisions about whether to fund a treatment," Nice said in a statement.

Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust, which has treated Mrs Sheppard locally, said it is "glad to hear" she is doing well.

"Unfortunately the drug she is receiving is not licensed for the exact type of cancer she has, and not studied extensively enough as yet for us to be able to prescribe it," the trust said in a statement.

- Published9 October 2016

- Published16 February 2016

- Published2 July 2015