Concrete to cobbles: Can a city centre go back in time?

- Published

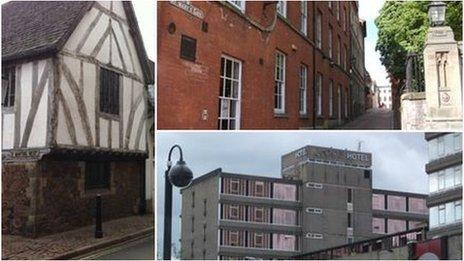

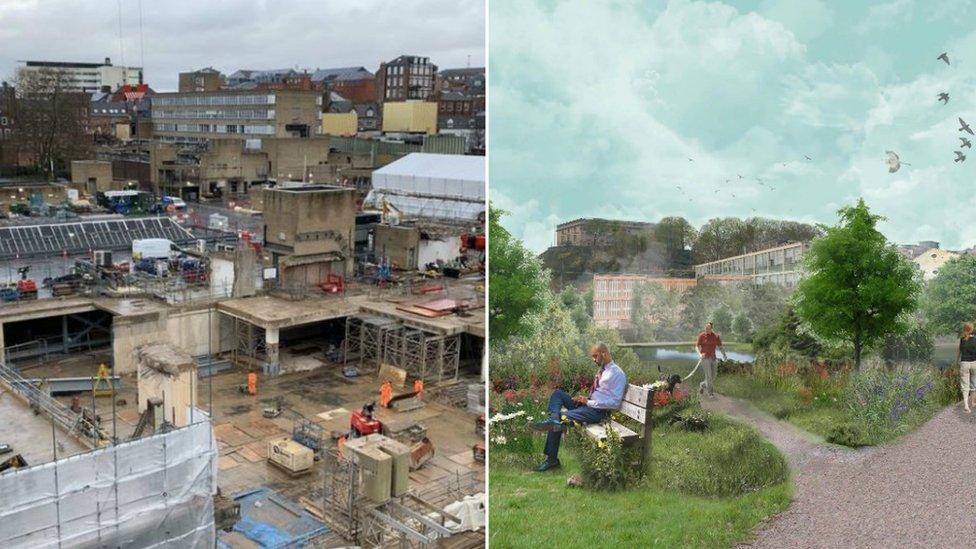

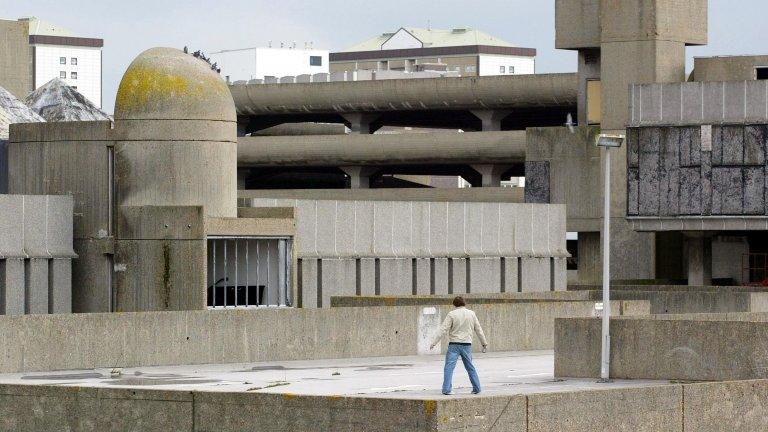

The Broadmarsh has lain derelict for months and will take a year to demolish completely

Have shopping centres had their day? With retail habits changing and the designs of the 1960s thoroughly dated, some centres are struggling to survive - but Nottingham has been offered a radical time-travelling solution to its own urban problem.

"Always unwelcoming, now it's apocalyptic".

It's not a tagline any city would want, but architect Peter Rogan's description neatly sums up the half-demolished hulk of Nottingham's Broadmarsh Centre.

The 1970s concrete and brick monolith has reached this sorry state by lurching from one failed renovation plan to another over the course of 20 years.

Major work finally got under way in 2019 - just months before owners Intu collapsed.

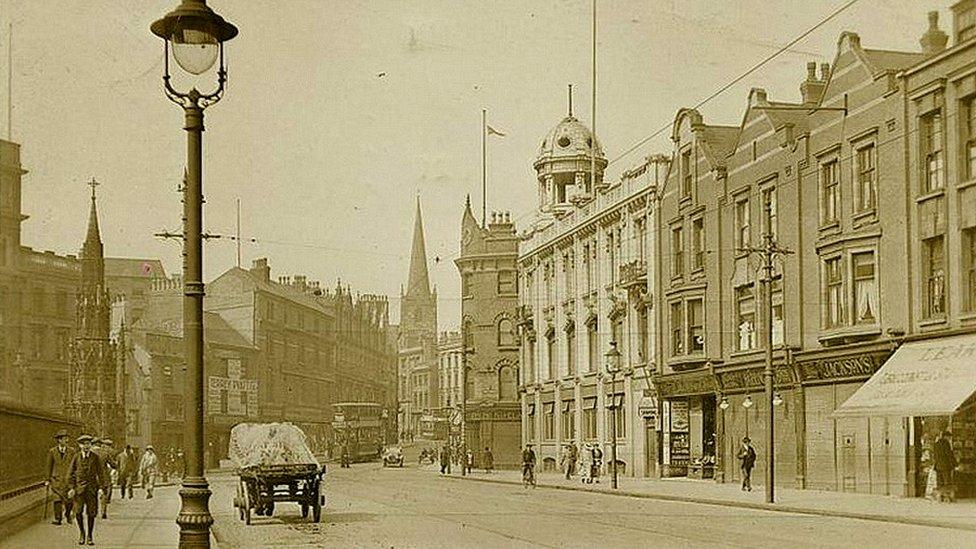

The southern road into Nottingham city centre, taken from almost the same spot as the image above

This left the Broadmarsh a shattered tangle of concrete beams and twisted metal.

Mr Rogan, a Nottingham-based conservation specialist, said: "It's awful. But it also represents an almost unique opportunity - to [look at] a huge swathe of the city centre and think again."

The Broadmarsh was built in the waning days of an architectural fashion - Brutalism - which gripped architects and civic authorities across the UK in the 1960s and 70s.

Buildings as diverse as Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral, National Theatre in London and Park Hill flats in Sheffield were constructed out of geometric, exposed concrete.

Manchester Arndale - the largest of that chain - also saw the demolition of part of the old city centre

But many people's most direct contact with Brutalism and its offshoots was in the city shopping centre - a trend started by Birmingham's Bull Ring - often in the guise of an Arndale.

Simon Allford, president elect of the Royal Institute of Architects, says: "These were inspired by American malls and were seen as symbols of modernity.

"And, at least in terms of footfall, they were successful for a time.

"But the cost was the large-scale developments obliterated streets and sucked the life out of cities and independent retail".

Building the new shopping centre meant sweeping away parts of the old city

All too often the "progress" championed by the planners and architects, from Manchester to Portsmouth, meant destruction for the fabric of the old city.

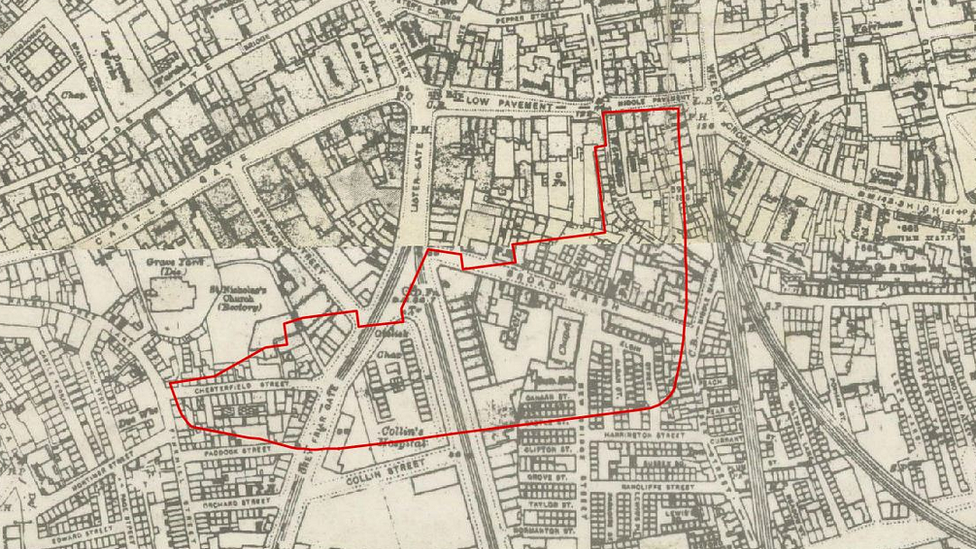

In Nottingham, the Broadmarsh development wiped out the old southern end of the city centre.

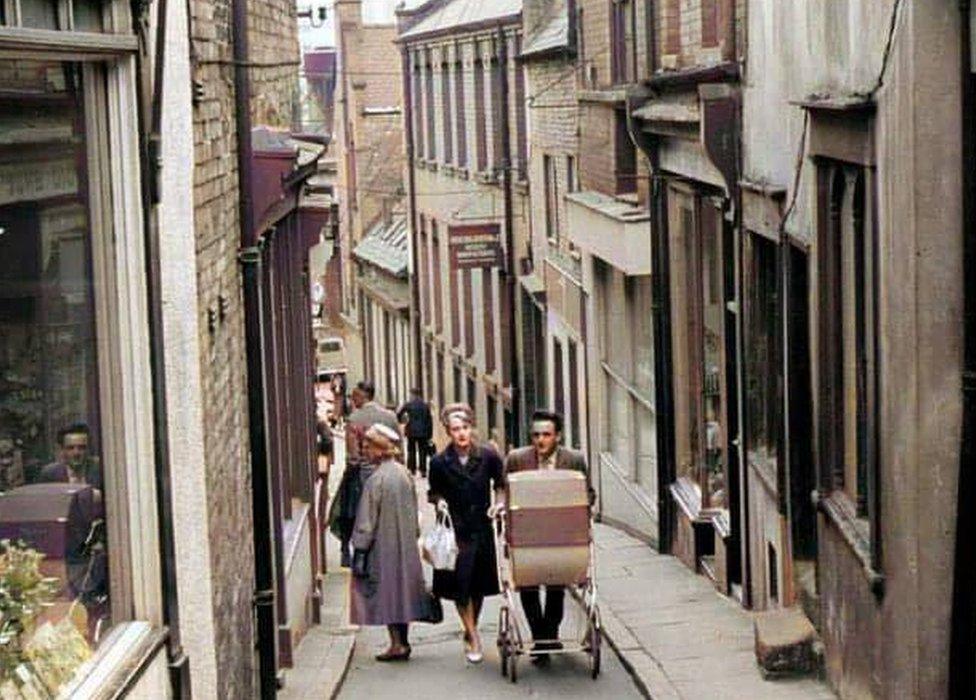

A street pattern which dated back to the Middle Ages, including the quirkily steep and narrow Drury Hill, was swept away.

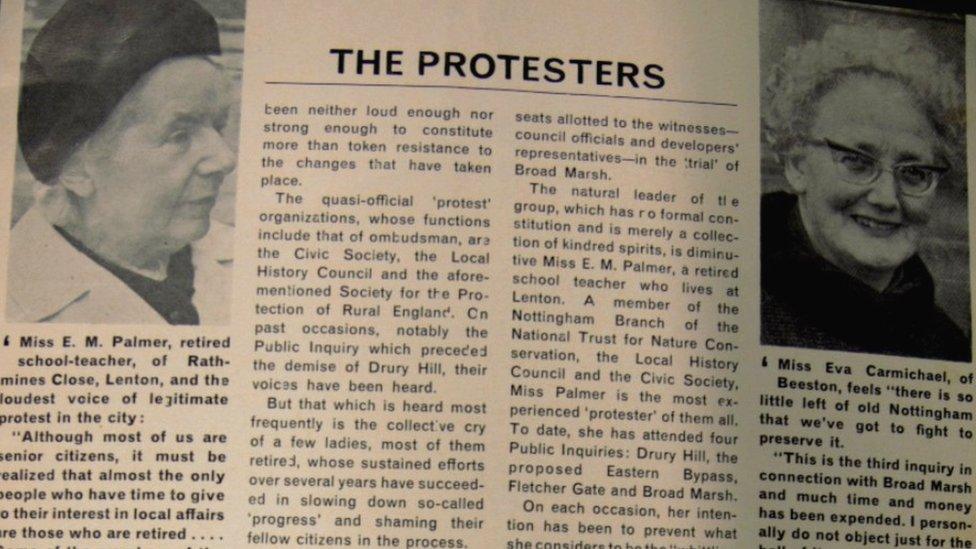

Broadmarsh: Planners v Public

Drury Hill was one of the narrowest shopping streets in England

The council's plan to turn the Broad Marsh area into a shopping centre was deeply unpopular when announced.

The focus was on the destruction of Drury Hill, a steep and narrow medieval road which was popular with locals and tourists alike.

Opposition was led by a group of women who wrote letters to everyone they could, and got local interest groups and the local papers to support their campaign.

Comparisons were made with other cities, such as York, which were said to preserve and celebrate their history - unlike Nottingham which seemed to be in the process of hiding or destroying it.

The Broadmarsh footprint over the old city streets - Drury Hill is the curving road in the top right of the red zone

Would not, they argued, a revitalised medieval street, already popular, attract more tourists and shoppers than a new shopping centre?

They caused enough of a storm that public inquiries were held at various stages of the development, where the protesters and council representatives each had to plead their case.

A representative of the architects, Ian Fraser & Associates boldly claimed: "We believe our professional skill and sensitivity will make the new area just as interesting and attractive as the old."

Documents show a Miss A.M. Mills called the plans "a cheap imitation of an American town".

Opposition was led not by students or radicals but a group of retired ladies

One unnamed official responded to the campaign by saying: "Isn't it ludicrous that a few old ladies should be allowed to spend time and money questioning the decisions of experts?"

Raising the temperature, it emerged the council had given permission for demolition before publicly announcing the scheme.

The planners won, though did make some concessions: some of the city's historical caves were preserved, but Drury Hill would be destroyed and the Broadmarsh Shopping Centre would be built.

A Miss E.M. Palmer said: "The council has robbed citizens of a favourite part of the city."

She reported being criticised by a planner for acting out of "sentiment", to which she responded that he did not live in Nottingham and: "How would he like a favoured part of his garden to be stolen?".

Shortly after being completed, the Broadmarsh was voted the ugliest building in Nottingham.

Source: Nottsflix, YouTube historian

And while shoppers got their chain stores under one roof, the Broadmarsh - along with a neighbouring multi-storey car park and four-lane through road - cut the city in two.

For a while, the Broadmarsh's mix of big, high street outlets, interspaced with burger bars and the occasional local name, drew in customers.

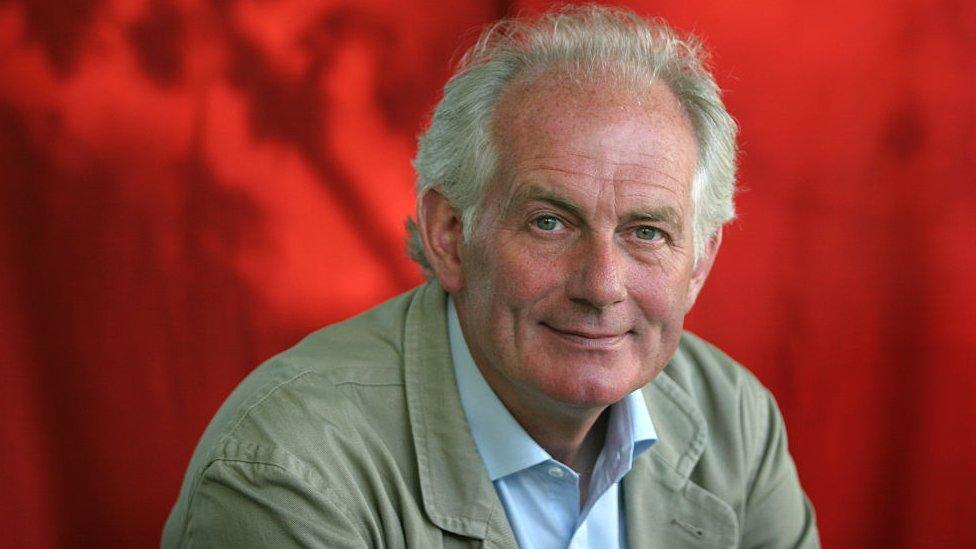

TV presenter Dan Cruikshank warns today's decision-makers must learn from the past

But now, changing retail habits, financial crashes, poor building quality and clumsy designs have left many cities wondering what to do with these behemoths.

Until recently the favoured solution was to remodel the building - a high-profile example was Birmingham's Bullring - but keep its purpose essentially the same: a big box full of shops.

Former owners Intu planned a facelift for the Broadmarsh - but little change in its fundamental use as retail space

How that turned out

But Nottingham has been presented with different challenge - the old building is all but demolished. Could it need a different solution?

The city council cannot be accused of underestimating the importance of the situation.

'Green spaces'

A major consultation attracted more than 3,000 responses and an independent panel has been appointed to consider the site's future.

David Mellen, the authority's leader, said: "The Broadmarsh Centre is one of the largest regeneration areas in any UK city and presents us with a once-in-a-generation opportunity to renew our city centre and our city's character.

"It's no surprise to us that people value a mix of green spaces and other developments, such as retail, housing and offices which, alongside our carbon neutral ambitions, we'd want to see reflected in the site."

The Broadmarsh's interior in the 1970s

He defended the legacy of the original Broadmarsh Centre, saying: "It was convenient for a lot of people; it was bustling in the 1970s.

"But we want to look forward and create something suitable for the future."

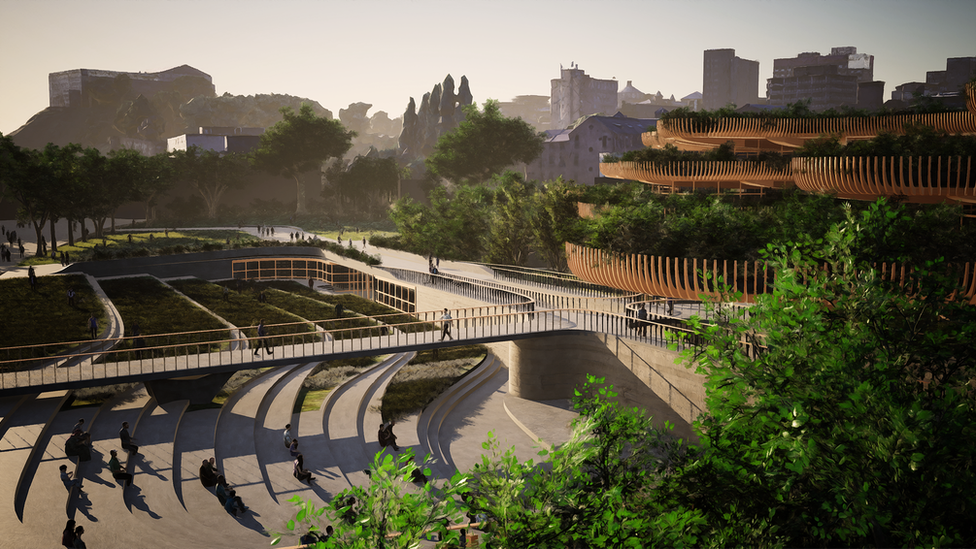

Suggestions have so far been varied - from keeping part of the old shopping centre building but adding a rooftop garden, through performance spaces with vertical farming, to converting the entire area into a nature reserve.

'Golden opportunity'

But can Nottingham do something completely different? Step away from the glass and steel blocks favoured by today's urban developers?

There is one simple solution but it is radically unusual...

Just put the old city back.

Peter Rogan's idea reestablishes old streets alongside a park and existing building projects

Mr Rogan said: "Let's have streets which twist and turn. The old streets were there for centuries, the new pattern is barely 40 years old.

"Rather than huge blocks which make windy canyons and fill them with identikit stores, lets have smaller, individual shops.

"I work with buildings hundreds of years old that, if you look after them, will last and last.

"But I see offices and shops from the last few decades whose leases are longer than their life spans, that are so poorly built they are not worth repairing."

The idea is backed by the city's Civic Society, which called it a "golden opportunity" to deliver "state-of-the-art, energy-efficient, traffic-free, mixed-use community".

What might seem like a (literally) monumental piece of nostalgia has some significant backers - and some examples to follow.

Bath's old Southgate Centre, shown here on a news item about its unpopularity, was built at a similar time to the Broadmarsh

The new Southgate was designed to reflect the Georgian architecture of the rest of the city

Mr Allford says: "Putting back the streets makes a certain amount of sense.

"These are streets which developed over hundreds of years and streets change rarely.

"I always look at the historical grain of a city to see what I can learn about how it works with the topography and how it has connected with the citizens over centuries.

"So looking again at those streets is not nostalgic; it is common sense."

Old Paternoster Square in London was built in Brutalist style right next to St Paul's cathedral

The new square is designed to be more in keeping with the history of the area and more attractive for people

TV presenter and architectural historian Dan Cruikshank has helped highlight the destruction of Britain's historical town centres in the 1960s and 70s.

He said: "Re-establishing old street patterns is a well-established policy and is often very sound.

"Interesting examples of replacing older developments with something more sensitive are Paternoster Square in London and Southgate in Bath."

An obvious issue is the cost of more traditional construction techniques - like those used in listed buildings - can be 30-50% higher than standard ones.

Nottinghamshire Wildlife Trust proposed turning the entire area into a nature reserve

But Mr Cruikshank warns today's decision-makers must learn from the - well-intentioned - mistakes by planners of the 60s and 70s.

"They wanted more humane, more hygienic cities with more light, away from the terraces and factories and overcrowding of the Victorian era.

"The problem was it was often done with a lack of respect for history and tradition.

"Too often it was done on the cheap, then this was compounded by not enough investment for maintenance."

Proposals for the area are many and varied, this one with an open-air performance space

Mr Allford feels whatever scheme is chosen, the city council must be both considered and yet also far-thinking, as demolition and rebuilding every 30 to 50 years is not sustainable.

He says: "The days of 'Brave New World' where we just rebuilt cities and told people to go live in them are long over.

"This needs to be a plan for the long-term. This mustn't just solve the problems of today but be adaptable enough to handle the challenges yet unknown.

"Retail is under a lot of pressure, so high streets may become smaller. Maybe schools and homes will move back in."

Many plans include housing, offices and open space

But Mr Cruikshank says more intangible criteria also play a part.

"Nottingham is a world-famous city with a great reputation for history of the most romantic sort.

"Any project must respect that.

"Individual character is what people remember, what can really define a place and give it a sense of belonging and soul."

Final demolition of the Broadmarsh Centre is due to begin in mid-April and will take 12 months.

The independent panel is expected to present its plans by the end of the summer.

Follow BBC East Midlands on Facebook, external, on Twitter, external, or on Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to eastmidsnews@bbc.co.uk, external.

Related topics

- Published16 February 2021

- Published4 December 2020

- Published27 June 2020

- Published21 June 2020

- Published1 November 2018

- Published2 August 2014

- Published3 October 2013