'Terribly sorry, your blood may be contaminated'

- Published

"It became quite clear this could be fatal and as a single parent that was a real shock," Joan Edgington said

"I received a letter from the transfusion body saying 'I'm terribly sorry but we think the transfusion you had may have been contaminated'."

Joan Edgington underwent surgery in 1991 and received a blood transfusion.

The "extremely fit" mother-of-two from Taunton, Somerset, said she felt things were "not quite right" when she struggled to recover after surgery.

She said: "The harder I pushed myself, I'd develop flu-like symptoms, my glands would swell and my joints ache."

She received the letter in 1994 and spent the next two months in "limbo" waiting for the test results.

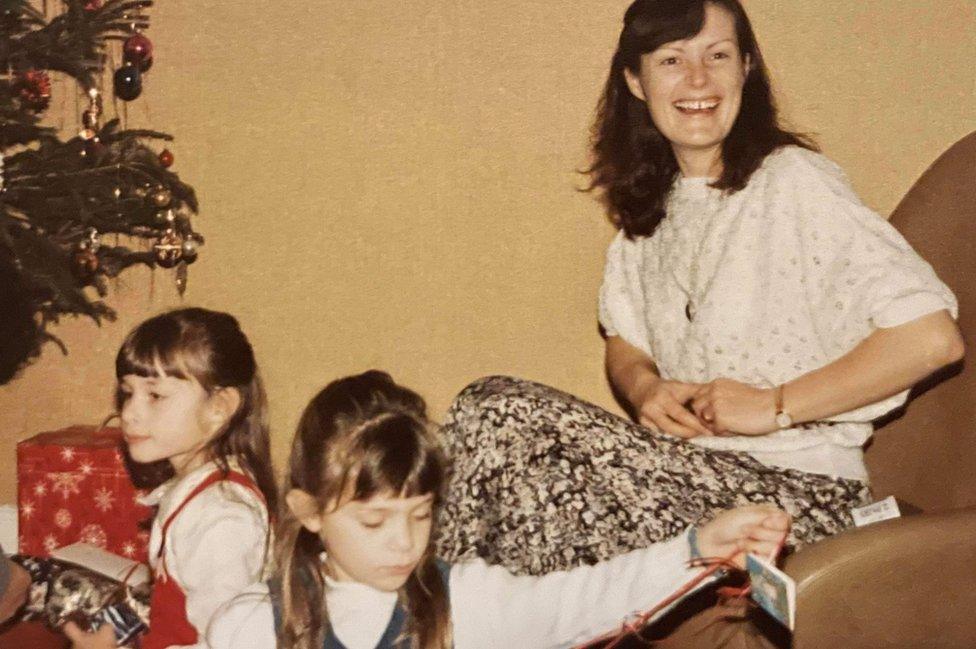

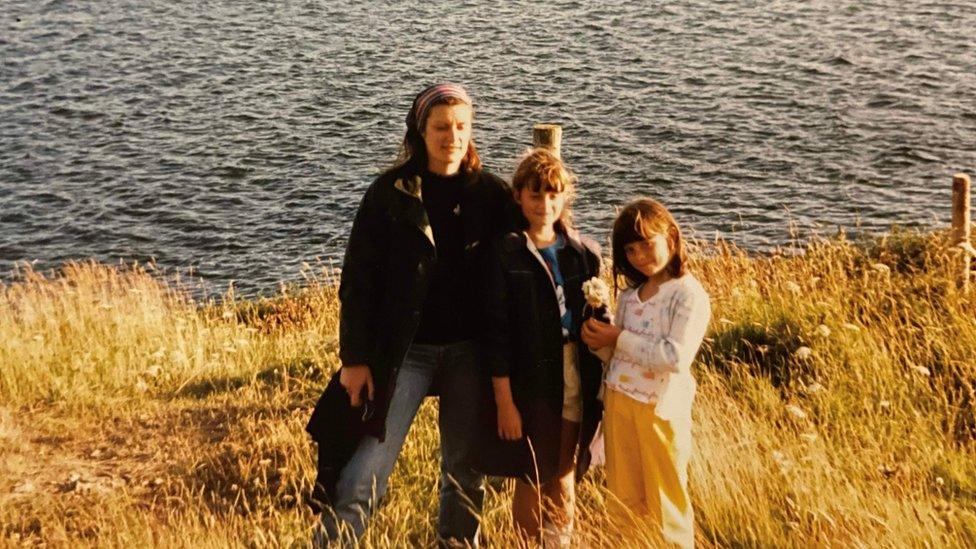

Ms Edgington was a single mother to two girls and was working full time when she was given infected blood

"I went into Musgrove [Hospital] and a very nice gentleman in a white coat took me into a side room - which was much better compared to some people's story who were just told in a corridor...

"And he said 'we can confirm you have Hep C, it is a blood born virus, be careful of any blood spill...' - and for a woman that's tricky - 'so don't share toothbrushes and razors and here's a leaflet'", she added.

Ms Edgington said she went and sat in the car for "a good half an hour" trying to order her thoughts: "What does this mean? Who do I go to? Who do I ask?"

'Could be fatal'

As a youth worker, working in outward bound, she had a very demanding job that started early and often finished late.

"So unlike people who live with Hep C for a long time, I was already aware that things weren't quite right.

"I used to try and describe it to my daughters as like a car that's running and you put your foot on the accelerator and there was just no extra energy…"

After learning about her condition Ms Edgington started trying to research it but it was her GP, who advised her not to look into it alone.

"It became quite clear this could be fatal and as a single parent that was a real shock, and trauma."

Ms Edgington said her daughters are what kept her smiling each day, in spite of her illness

She said her main focus was to get treatment because "I did not want to leave my children".

"Although every day is a struggle... my daughters are what got me up each day and gave me purpose. I felt very blessed to have them."

"Permanent damage"

By 2004-2005, she said her liver was so damaged she was "deemed ill enough" to qualify for a trial.

"They did say it was a new treatment, that there were side effects. At no point did they say there would be permanent damage."

The treatment was "brutal", she said.

Ms Edgington was put on a drug they later learned had been created for cancer in the US but was rejected because of the extreme side effects.

She was left with nerve damage in her fingers and toes, but she said the biggest impact was the damage it caused to her immune system.

After needing three rounds of antibiotics to treat a kidney infection about six years ago, her body went into "overdrive".

She said it was so severe she was put into haematology as doctors thought she had leukaemia.

After being observed for a year, she was two weeks away from beginning chemotherapy for leukaemia, which "I didn't have, because eventually my body settled down", and she said they realised it was not cancer.

Ms Edgington, who was 'extremely fit' before the transfusion, struggled to continue working afterwards

Hepatitis C (HCV) is a virus that infects the liver and is passed via blood-to-blood contact.

Ms Edgington was 37-years-old when she was infected with the virus, in the infected blood scandal, which has been called the biggest treatment disaster in NHS history.

She was one of a group of patients given a contaminated blood transfusion after childbirth, surgery or other medical treatments between 1970 and 1991.

The inquiry estimates between 80 and 100 people were infected with HIV, and about 27,000 patients were infected with Hepatitis C.

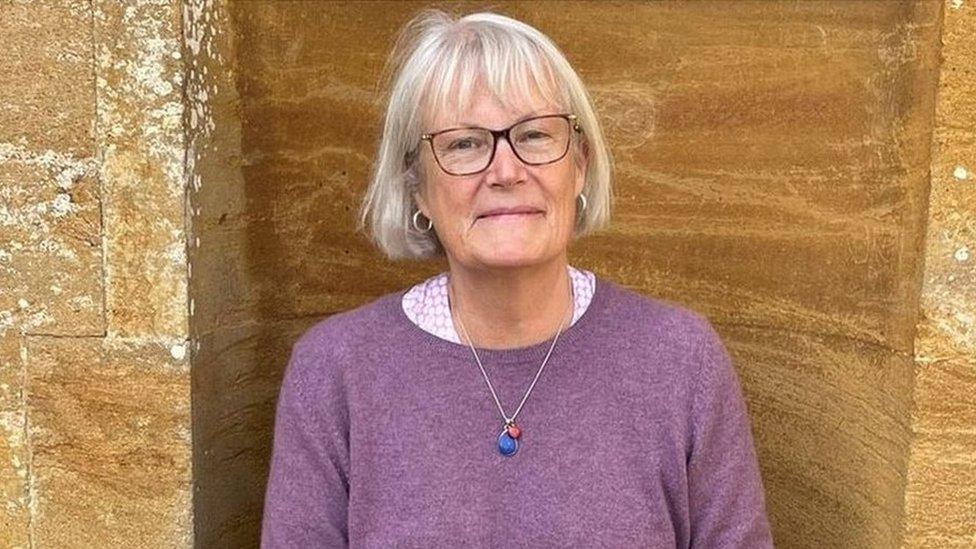

Ms Edgington has given evidence in the inquiry, which began five years ago, calling for "the powers that be" to be held to account.

Read more on the infected blood inquiry

Ms Edgington said finding out she could die was traumatic, particularly as she was a single mother to two daughters at the time

Ms Edgington said the inquiry had been a "fascinating process".

"It was wonderful to be there at the launch when for the first time you were in a room with thousands of people that understood your story.

"Because up until then we were all isolated, dealing with GP's who were kind and supportive - or not - but for them, we were unique.

"They didn't have many patients that had been through that or didn't know they were infected.

"And to be in a room where you're validated, and you're listened to, where other people understand the story was really powerful."

However, she said as the inquiry has gone on, "listening to everybody's story and getting the full extent of the tragedy has been heart-breaking.

'In denial'

"One of the things we've really struggled with is we have to keep telling our story individually".

She said if there was national recognition of common problems and issues, there would be continued healthcare for them and those bereaved, but there was not "because there are a lot of people in the profession in denial".

Ms Edgington said she wanted "the powers that be" to be held to account

"Hundreds have died just over the period of the inquiry. That's why I'm here. There's not many of us left to carry the banner," she added.

Ms Edgington told BBC Somerset that although the government has a cut off point of September 1991 for contaminated blood, which is when they tested from, blood products and blood donations already in the system were not recalled, and she urged anyone who received a transfusion into the mid 90's to get tested "just to be safe".

She said anyone who had received a transfusion abroad should also get checked: "The tests are simple. It's just a blood prick sample and the meds are fine [now]."

She said she hoped victims of the scandal who had not been recognised up until now would be recognised and that "politicians are held to account".

The inquiry will publish its report on 20 May and the government said it would be inappropriate for it to respond until its full findings had been published.

Follow BBC Somerset on Facebook, external and, X, external. Send your story ideas to us on email, external or via WhatsApp on 0800 313 4630, external.

Related topics

- Published22 April 2024

- Published22 April 2024

- Published17 August 2022