Ashok Kumar: Teesside's gentle, tenacious and respected pioneer

- Published

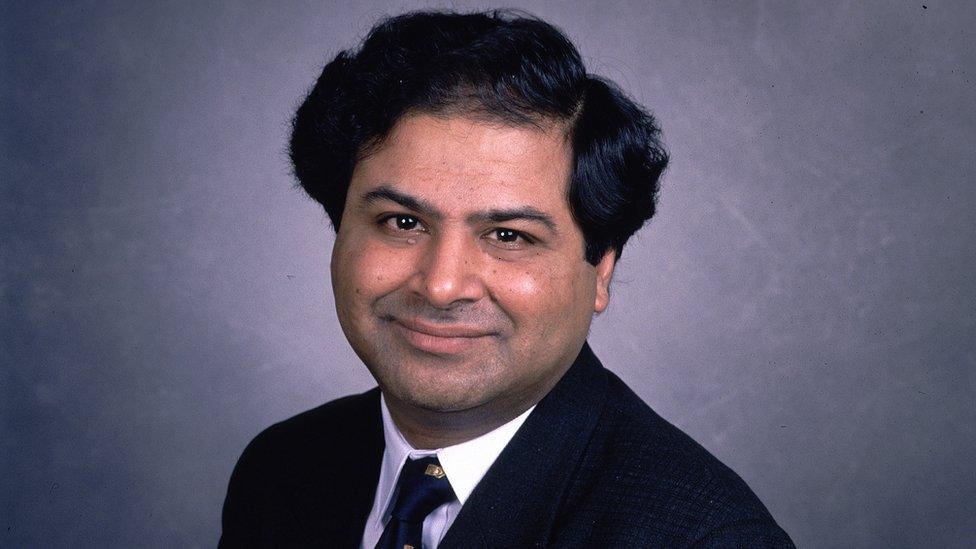

Ashok Kumar, who referred to himself as black throughout his career, was first elected in 1991

Ashok Kumar was the first black MP to represent the north-east of England in Parliament. The Indian-born chemical engineer overcame racism and personal tragedy to become one of Westminster's most respected MPs.

Thirty years after Kumar's by-election win, BBC Politics North editor Michael Wild looks back at his career.

On a bright spring afternoon in March 2010 a coffin is carried through the cobbled streets of a small market town on the edge of the North York Moors.

Knots of people stand in shop doorways, a few clutch shopping bags, others have hankies wrapped tightly into their hands.

In front of the funeral cortege walks an elderly man, slightly stooped with head bowed, flanked by family. Behind is carried the body of his 53-year-old son, the Labour MP Ashok Kumar.

Dozens of mourners paid their respects as Ashok Kumar' funeral cortege passed through Guisborough

At Guisborough's red brick Methodist church, Labour minister Harriet Harman speaks of a "tragic loss at such a young age" while Ravi Kumar describes his brother as "a man who could feel other people's pain". There's a round of respectful applause as the hearse moves off for a private burial close to the family home in Derby.

This was a corner of the North East that had taken Kumar to its heart, but it had been a long and painful journey in which he had to confound the critics and overcome racism.

Kumar had come to England as a young child with his parents and two brothers from Haridwar, then in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh.

His father, a postmaster, struggled to find work. Kumar stuck to his studies, initially at the local secondary modern, then at Aston University where he completed a degree in chemical engineering, followed by a masters degree and then a PhD.

Kumar came to the UK as a child from Haridwar, then in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh

Armed with qualifications, and after three years at Imperial College London, he joined British Steel on Teesside as a research scientist in the mid-1980s. He also had strong political views and, outside work, was a very hands-on community organiser keen to address local issues.

By 1987 he was Middlesbrough's sole Asian councillor.

When the sudden death of Conservative MP Richard Holt in 1991 left the nearby parliamentary seat of Langbaurgh vacant, Kumar's supporters were keen to see him shortlisted to fight the resulting by-election.

He had trade union backing and first-hand knowledge of the local steel industry, yet some older Labour members were worried over how voters would respond to an Indian candidate.

Langbaurgh was just a few miles from the solid Labour seats of Hartlepool, Middlesbrough, Stockton North and Redcar but it was a different world. It encompassed a scattering of industrial towns like Skinningrove and Loftus but more typical were remote farming communities stretched out along the Cleveland Way and the genteel coastal resort of Saltburn.

It was one of the "whitest" parliamentary seats in the country - middle England writ large. Even the name (pronounced Langbarf) could catch out unwary incomers.

Saltburn was a far cry from its more industrial neighbours

There were concerns about Kumar's personality too. With a general election imminent, the seat would be fought for in the national media spotlight. It was not an environment that naturally suited a quietly spoken councillor who would enjoy evenings alone in his study reading political philosophy and listening to jazz.

On occasions, Kumar did join town hall colleagues in the pub where he would nurse a half of bitter through a long evening of political debate. But he was at heart an introvert who remained awkward in social gatherings.

Despite misgivings, he impressed party members with his passion and a deep understanding of the local industries that mattered - chemicals and steel - and was quickly confirmed as the candidate.

But the by-election would prove even more difficult than many imagined.

Each morning on the campaign trail began in much the same way: the candidate on a make-shift podium, flanked by one or two shadow cabinet members, each wearing the obligatory red rose. A long line of political heavyweights from the opposition front bench - Margaret Becket, John Prescott, John Smith, Gordon Brown - headed to the North East. Traditional by-election photo opportunities were arranged at the local maternity unit, ICI training centre and colleges.

The quiet, rather diffident, candidate was happy to leave others to deal with the media inquisition. But on Monday, 19 October - only the third full day of campaigning - reporters arrived to find Kumar's seat at the morning news conference empty.

Harriet Harman made a brief statement explaining that his mother had died suddenly and he had returned to the family home. Surprisingly, no attempt appears to have been made to suspend campaigning and Ms Harman went on to meet voters at Guisborough Hospital as planned.

Whether he was given any choice in the matter or not, Kumar was back on the campaign trail the next day.

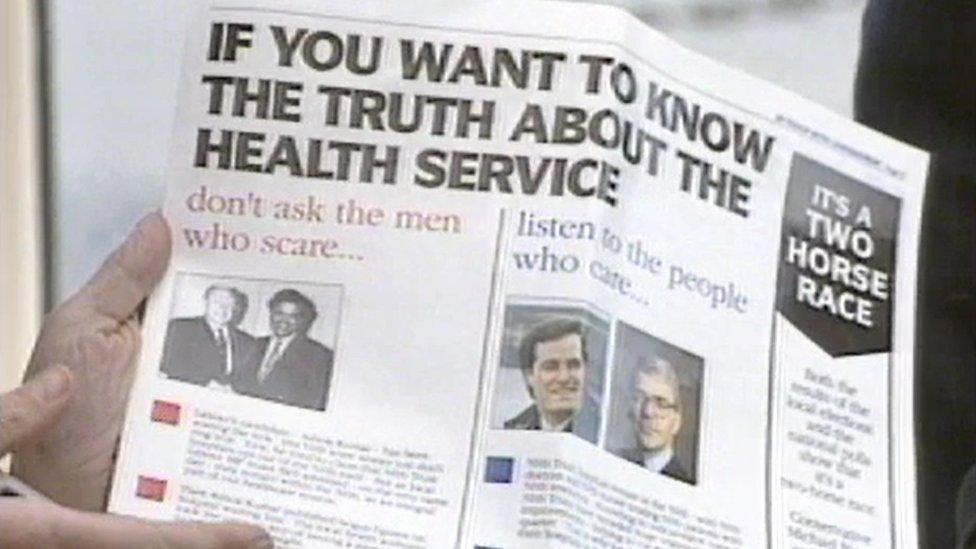

Labour claimed the Tories' use of an opponent's picture in their own election material was designed to draw attention to his Asian heritage

The Conservatives, meanwhile, kept the pressure up on what they saw as a weak candidate. Photographs of Kumar appeared almost as often in their election literature as they did in Labour's - which was regarded as a ploy to focus on his Indian heritage.

Labour also viewed the slogan "Your local Tory - your straight choice" as an unsubtle dig at their man's lack of wife and children - a claim Conservatives flatly rejected.

Unofficial pamphlets were circulated with a more openly hostile and ugly tone. They used explicitly racist language.

By 5 November, two days before the vote, electioneers and media alike were tiring of the lacklustre campaign enlivened only by the appearance of "Miss Whiplash" Lindi St Clair standing on a platform of sexual freedom.

Yet race continued to bubble away under the surface.

Among the candidates was Lindi St Clair - known as Miss Whiplash - standing for the Corrective Party

On the final day of campaigning John Hindmarsh, a consultant at South Cleveland Hospital, wrote an open letter to Kumar accusing him of putting out false statistics about the NHS. It ended with the words: "For Allah's and God's sake, leave us alone".

Hindmarsh was a member of Darlington Conservatives but their candidate Michael (now Lord) Bates immediately disowned the letter. Labour's campaign coordinator Jack Cunningham was outraged and used an appearance in the Commons to denounce what he called "contemptible tactics of gratuitous abuse, innuendo and vilification".

He went on to predict Kumar would make history when the results were finally declared. Labour did win but the margin of victory was hardly historic: a none too convincing majority of 1,975.

Kumar was said to have been a tenacious advocate for his constituents

Labour leader Neil Kinnock said it was to the credit of voters that they had defied Tory prejudice, although Conservative minister David Mellor claimed unfounded allegations of racism were a smokescreen to disguise Labour's poor performance.

As for Kumar, he told reporters it had been a "very painful" campaign and he had been saddened by the personal attacks.

The truth was Kumar's sorrow was far deeper; he had hardly begun to grieve for his mother before he was travelling to Westminster to be paraded as Labour's new MP.

It was to be a short-lived introduction to the green benches because in March 1992, John Mayor called a general election.

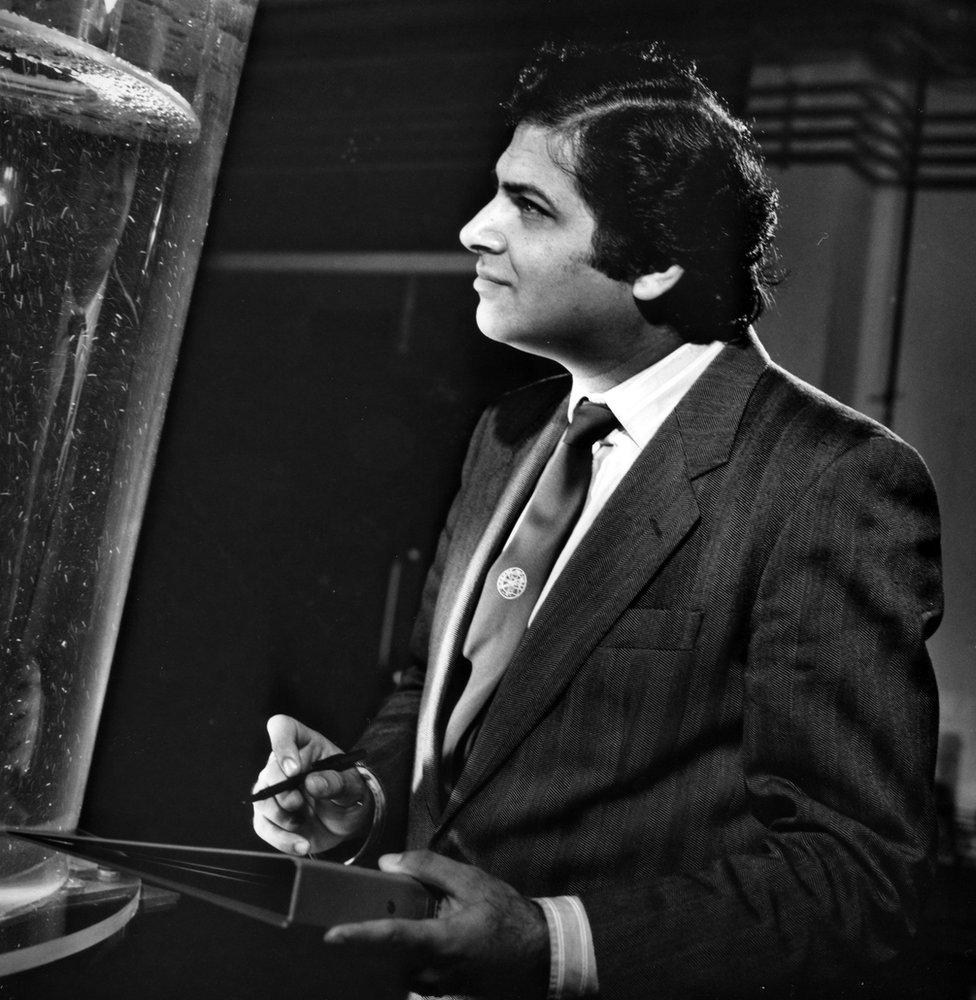

This time Conservative Michael Bates triumphed and Kumar returned to working for British Steel.

Kumar worked at the Materials Processing Institute in 1992, then the British Steel Teesside Technology Centre

By the time Sunderland MP Chris Mullin met Kumar four years later, he had been re-selected to fight for the re-named the Middlesbrough South and East Cleveland constituency.

In his diaries Mullin said he had found Kumar "very gloomy" about his chances of winning. He need not have worried. He re-took the seat in Tony Blair's Labour landslide of 1997 with a majority of more than 10,000.

Black contemporaries in the Commons at that time, such as Bernie Grant and Diane Abbot, were few and mostly represented inner-London constituencies with strongly left-wing electorates. By contrast, Kumar was a political moderate which suited many of his North East constituents just fine.

Although a secularist and member of the British Humanist Association, he did feel the need on occasions to speak up for those who shared his heritage, such as condemning verbal abuse of Hindus after the bombings on 7 July 2005. He faced further racist attacks too, including a death threat in 2004 from a right-wing splinter group.

But his biggest personal struggle was over the Iraq war which he staunchly supported - against the wishes of many members of his own local party. In other contentious areas, like tuition fees, he also remained loyal to New Labour.

In November 1987 Labour Party leader Neil Kinnock celebrated his four new black Labour MPs

Kumar was an MP more likely to be found in the Commons library than the Stranger's Bar and his failure to be clubbable probably counted against him when it came to securing promotion.

He was parliamentary private secretary to Hilary Benn, but never made it beyond the backbenches. Instead, he put his specialist knowledge to good use as a member of the Science and Technology Select Committee and as an advocate for the steel and chemical industries.

His death came in the middle of a fierce campaign to save jobs at the Corus Teesside Cast Products steel plant in Redcar in 2010. He had left Westminster on the Friday night, returning to his home in Marton, where he lived alone. Only when office staff failed to make contact with him on the Monday morning did worries grow.

Kumar had died from a heart attack.

What followed was an outpouring of emotion that went far beyond routine tributes. Blair said, as a neighbouring MP, he had seen Kumar's commitment to the North East at first hand.

Gordon Brown, then prime minister, described him as a "tenacious campaigner and a passionate advocate for the people of Teesside".

"His expertise and wise counsel will be sorely missed at all times in this House," he told MPs.

He was loved in our area, not just for his tenacity and work ethic but for the warmth that emanated from his every pore. He will be a hard act to follow.

But it was in the letters pages of local newspapers and the hundreds of calls to his office that voters and friends paid their respects.

Kumar had been assiduous in his dealings with constituents; relentlessly pursing their problems with the help of a dedicated and experienced backroom team.

Losing the seat months after his first by-election win left him fearful history might repeat itself. So he determined never to take supporters for granted. His level of individual contacts with constituents was among the very highest of any MP.

On the day of his funeral, a reporter asked some of those gathered outside the church for their thoughts. One said Kumar was "there for everybody" regardless of "what culture you were from".

Another feared his efforts to save the steelworks may have cost him his life. "He fought tooth and nail for that place and look where it got him," he said.

Kumar spent the last few weeks of his life trying to find a buyer for the mothballed Corus plant

His agent and close friend David Walsh said Kumar never considered himself part of the Westminster establishment. He felt himself an outsider in the scientific world too.

"People at the high table of science at that time were very white," he said. "His intellectual achievements were great but he felt he was sometimes regarded as just an Indian chemist."

Mullin, who had an office opposite Kumar in the Commons, agrees the MP's unassuming manner allowed his achievements to be overlooked.

"He had to overcome considerable prejudice and it wasn't confined entirely to people from other parties," he said.

"He was in that very real sense a pioneer."

Follow BBC North East & Cumbria on Twitter, external, Facebook, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to northeastandcumbria@bbc.co.uk, external.

Related topics

- Published18 March 2012

- Published2 October 2010