State papers: Clinton's peace envoy plan 'concerned' British

- Published

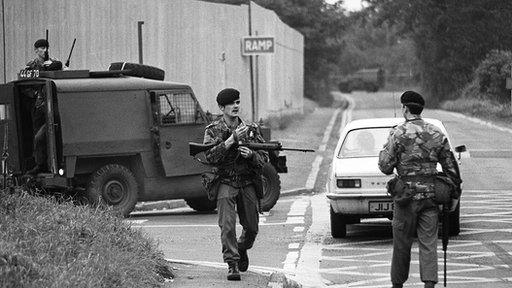

US President Bill Clinton pictured with then SDLP leader John Hume during a visit to Northern Ireland in 1995

Newly released government papers have revealed that a 1992 plan from Bill Clinton to appoint a peace envoy to Northern Ireland caused deep concern among British diplomats and the Northern Ireland Office (NIO).

They also show that early in the peace process, Martin McGuinness sent letters to leading Conservative politicians.

The documents were released on Friday by the Public Record Office (PRONI).

The files give a behind-the-scenes insight to the early 1990s.

'Very adverse reaction'

As a US Presidential candidate, Bill Clinton wanted to appoint a peace envoy to Northern Ireland, however the reports show how much the government opposed the idea.

He had been urged by several high profile Irish Americans to appoint such a special representative.

After his presidential victory, in a telegram to the British Embassy in Washington in December 1992, the British Ambassador to Washington, Robin Renwick, told the Northern Ireland Secretary, Sir Patrick Mayhew the idea "caused a lot of concern and produced a very adverse press reaction in Britain."

Eventually, in 1994, George Mitchell was appointed and would later go on to chair the talks that led to the Good Friday Agreement.

Martin McGuinness sent letters to leading Conservative politicians

The papers have also revealed that in the last years of the Troubles, Martin McGuinness wrote a number of personal letters to Conservative politicians.

The letters, which were an attempt to initiate discussions, were sent to the then Secretary of State for Northern Ireland Peter Brooke and the former Prime Minister Sir Edward Heath.

In 1992 Mr McGuinness wrote: "Dear Mr Brooke, I found it interesting that in a BBC interview shortly after you left office as secretary of state you expressed your regret at never having met the Sinn Féin President, Gerry Adams during your time in Stormont."

He added that while "difficulties may still exist to prevent you undertaking such an initiative," he would still like to "explore the possibility that a meeting between yourself and other members of the Conservative Party with representatives of Sinn Féin could take place at some time in the future".

In a memo to Sir Patrick Mayhew, John Chilcot, head of the NIO, said the secretary of state had endorsed his advice that Mr Brooke should not "say anything in reply to Mr McGuinness other than what will be, no doubt, a polite refusal".

'Catholic majority?'

The files also contain correspondence between civil servants in the NIO about the possibility of a united Ireland, with one official writing that strategies should be in place in preparation for such a scenario.

In a 1991 note to officials, D A Hill from the NIO said there was "an underlying assumption that, at some point, the Catholic population would become a majority".

He asked population expert, Edward Jardine, if and when Catholics would become a majority in Northern Ireland.

As a result of this report, Mr Hill said that while in the late 1970s and early 1980s it was projected there would be a Catholic voting majority by 2036, there had recently been a decline in the Catholic birth rate with the Protestant birth rate remaining stable.

"The recent dramatic collapse of the birth rate in the Republic made a Catholic majority in the north less likely," he added.

'If you cannot beat them, join them'

However another official, Ms Pat Ransford said various factors could "tip the balance" towards a higher Catholic majority and subsequent support for a united Ireland.

Although she also said: "One hypothesis might be that Catholic support for unionism is partly explicable as adaptative survival behaviour - crudely put, "if you cannot beat them, join them".

She concluded that it seemed worthwhile having "strategies that do not suppose that a possible majority for constitutional change early next century is totally remote as a possibility".

- Published3 January 2014

- Published1 August 2013