Armistice message to Ulster Division found a century on

- Published

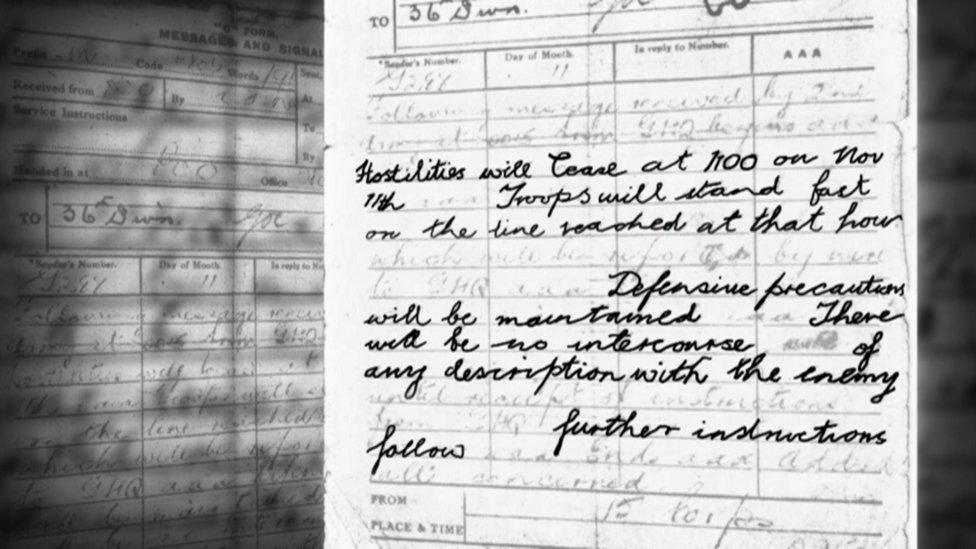

The Armistice message ordered that all hostilities would cease at 11:00 on November 11 1918

It was one of the most important messages to be sent in the past 100 years.

It was carried by a Dublin man serving as a despatch rider with the 36th Ulster Division during World War One.

It was the signal from Army headquarters to the commanding officer of the Ulster Division to cease hostilities on 11 November 1918.

The message effectively brought to an end four long years of carnage and slaughter in northern Europe.

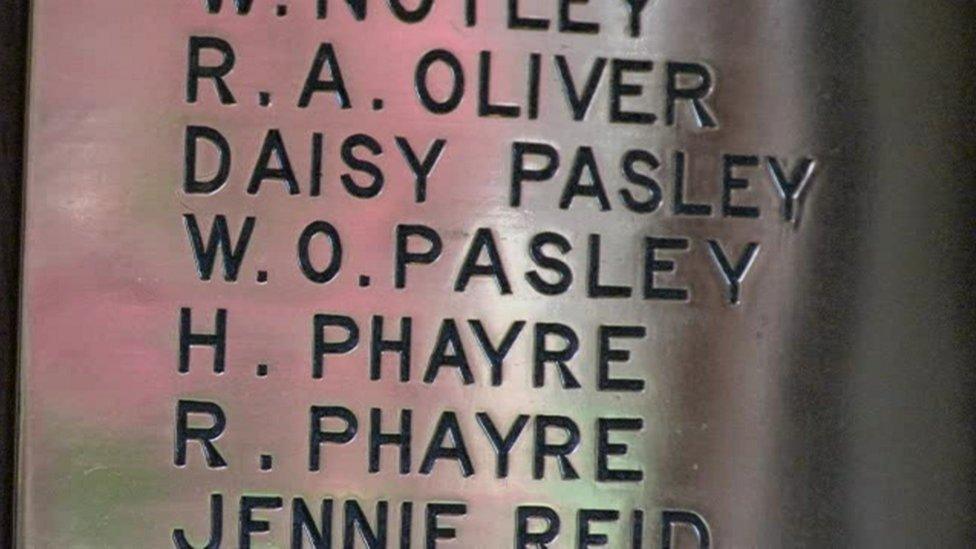

At Methodist Centenary Church in a leafy suburb of south Dublin, the name Ormsby Pasley is etched, along with many others, on the brass plate of the war memorial plaque in the porch.

Ormsby Pasley is commemorated on a plaque in Methodist Centenary Church

Ormsby was a despatch rider with the Royal Irish Rifles and, on that fateful morning nearly 100 years ago, he was handed a signal and told to deliver it to Major General Coffin who commanded the 36th Ulster Division.

It was the news they had all been waiting for.

'Didn't speak about the war'

The orders were that at "11:00 all hostilities should cease" and the soldiers should "stand fast" at whatever point on the front line they had reached.

It also instructed that "defensive precautions will be maintained" and warned the troops that "there will be no intercourse of any description with the enemy".

The message ended: "Further instructions will follow."

Ormsby Pasley, recognising the significance of the order, kept a copy, which he stuffed in his pocket and brought back to Ireland with him more than a year after the Great War ended.

It hung in a frame on a wall in his home for many years and, although faded by sunlight, is still legible today.

Ruth Warren said her grandfather "didn't talk much" about his experiences in World War One

"He was delivering the telegram to say the war was over and he kept a framed copy," his granddaughter Ruth Warren explained.

"He didn't talk much about the war, according to my parents. However, it must have been great news (that) it was all going to be over."

'A gotcha moment'

Robert Simpson, who is married to Ormsby's granddaughter, has been involved in pulling the family jigsaw pieces together to tell his story in time for the Armistice Centenary.

"A few months ago we were cleaning out my parents-in-law's house and we came across the framed note of the armistice. It was a real 'gotcha' moment," said Robert.

"I can see why Ormsby kept it because is was so important."

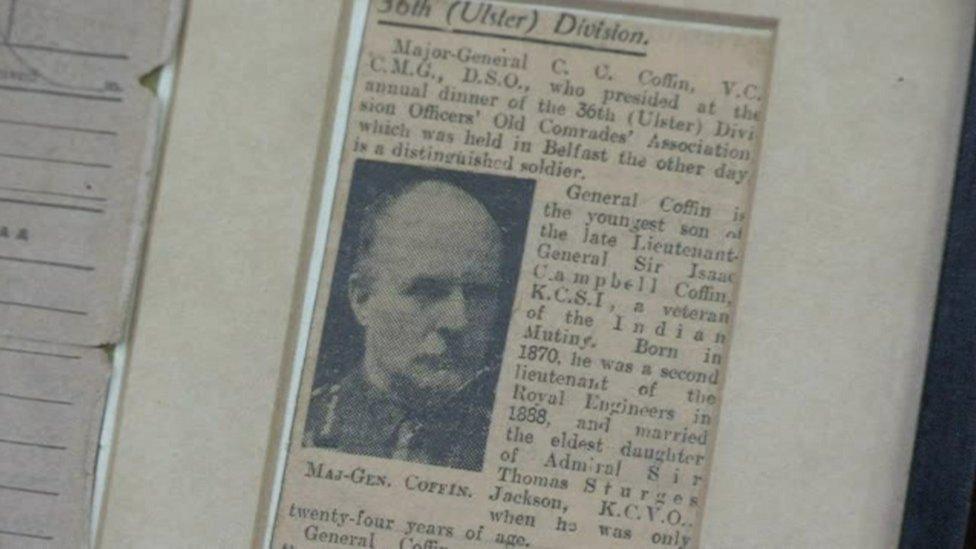

The note was passed to General Clifford Coffin, who was head of the 36th Ulster Division

He added: "But what puzzled us was that he framed it beside a photograph of General Clifford Coffin and we had no idea what that was about.

"We did a bit of research and discovered that he was the officer commanding the 36th Ulster Division at that time. So Ormsby would have handed him the note at around 7.50am that morning."

While it has faded over time, the words when enhanced are no less powerful, despite the decades exposed to sunlight.

The Armistice 100 years on

Long read: The forgotten female soldier on the forgotten frontline

Video: War footage brought alive in colour

Living history: Enniskillen first to hear about the Armistice

When he returned home to Ireland after the Armistice, Ormsby Pasley rode a motorcycle just like the one he used on the battlefields of Europe.

But like many other servicemen, he didn't talk much about the war.

'He was brave'

It's only in recent months, in the run-up to the centenary of Armistice Day, that the family has started piecing together his story.

"Each family had a different little piece of the story and we're only now putting it all together," said Ruth Warren.

Ormsby Pasley's great-grandson, 12-year-old Oscar, said he was "brave to do what he did"

"Everyone seems to have a relative connected with this war, which Ormsby was lucky to have survived.

"A girl I work with has a similar story about her great uncle who served in the army during the Great War. So it goes on."

Another relative with his own views on the carnage is 12-year-old Oscar, Ormsby's youngest great grandson.

"I'd have been really scared, I probably wouldn't have come out of the trenches at all. I didn't know much about my great-grandfather but I think he was sort of brave to do what he did."

About 100,000 soldiers returned to Ireland after the Armistice to "a country changed... changed utterly", in the words of the poet William Butler Yeats.

In more recent years, that has changed again both politically and socially when it comes to remembering the dead of the Great War.

- Published9 November 2018

- Published5 November 2018

- Published4 November 2018