David Sterling: No ministers could become 'new normal'

- Published

- comments

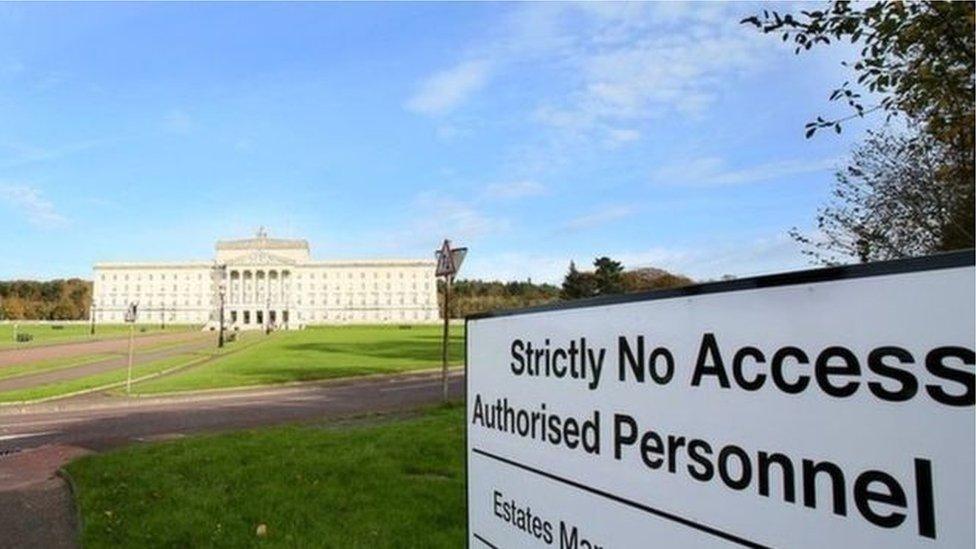

David Sterling, the head of the NI Civil Service, made the warning in a BBC documentary

The head of the Northern Ireland Civil Service has said he is concerned the absence of elected ministers could become "the new normal".

Civil servants have been in effect running departments since the executive collapsed two years ago.

However, because they are not elected, they are unable to make major policy decisions.

David Sterling told the BBC there had been a "slow decay and stagnation" in public services.

The top civil servant at Stormont, Mr Sterling said that there had not yet been a "cliff edge moment", where the workings of government departments had collapsed, but noted that there had been a deterioration in areas.

He made the comments during an interview for the BBC Radio Four documentary "Who Needs Politicians Anyway?", which examined the impact of the political deadlock on Northern Ireland.

Mr Sterling pointed to particular challenges regarding healthcare, education and criminal justice.

He has previously warned that urgent reforms are being held up by the impasse. and that some social housing may have to be "mothballed" if ministers do not return, with a maintenance backlog in the state's housing stock, and housing provision needing to be "reconfigured."

Mr Sterling said: "There are big issues which need to be addressed by ministers, and in the absence of that there is a real risk that we might actually have to mothball some of our social housing."

The power-sharing Executive at Stormont collapsed in January 2017

The long Stormont stalemate began in January 2017, when the power-sharing partnership of the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) and Sinn Féin fell apart.

The final row between them was over a botched green energy scheme, the Renewable Heat Incentive.

When the late Martin McGuinness resigned as deputy First Minister, the rules of mandatory coalition meant DUP leader Arlene Foster was automatically put out of her job as First Minister.

Several rounds of talks since have failed to restore the devolved government.

There have been no substantive negotiations between the parties since February 2018.

'We're talking a generation - perhaps two'

The only executive minister who was not in one of the two main parties was Claire Sugden - an independent unionist who was in charge of the Department of Justice.

Former minister Claire Sugden has said the political system will take a "generation - perhaps two" to fix

She highlighted the stalling of legislation on domestic violence - which she had initiated - as a particularly disappointing result of the political deadlock.

Ms Sugden acknowledged that if the executive returned "the problems that exist today are not going to go away tomorrow".

"The system is broken and to fix that, we're talking a generation - perhaps two," she said.

"The problem we have now is that we don't even have anyone starting that process because there are no ministers."

The word "limbo" is often mentioned by politicians, public service workers and others to describe the very unusual state of governance in Northern Ireland.

The biggest problem is the lack of medium-to-long-term strategic planning.

The day-to-day effect of the administrative autopilot may not be obvious to many citizens.

'Safety net'

That has led the political scientist Professor Matt Flinders to muse: "One of the great risks of Northern Ireland is that allowing life to go on might add another layer to the argument of 'why do we need politicians?'"

The academic from Sheffield University is concerned about the widespread cynicism in relation to politics across much of the world.

He has warned that the symbolic value of politicians is significant as well as their function as legislators.

"Politicians act as a lightning rod for social pressures, and frustrations, and antagonisms," he said.

Cancer patient Melanie Kennedy has lobbied ministers and civil servants to bring about changes to the process for funding drugs

"By doing that, they are really providing a very important safety net. It's only when that disappears that things can get very scary, very quickly."

Melanie Kennedy, from Bangor, is more acutely aware than most of the difficulties caused by the empty Stormont benches.

Five years ago, she was diagnosed with breast cancer - and raised money to pay for a drug which is only available privately in Northern Ireland.

She lobbied ministers, then civil servants, for the drugs funding process in Northern Ireland to be brought into line with the rest of the UK.

In September 2018, the NI Department of Health announced the changes Melanie had been campaigning for.

The department said the decision was "clearly in the public interest" - one of the tests which civil servants must apply to any decision to assess if it is lawful in the absence of the executive.

Ms Kennedy runs the Northern Ireland Cancer Advocacy movement, which supports patients with the disease.

She has given civil servants credit for listening to her - but wants to see devolved government restored.

"The longer this goes on, the more people are suffering," she said.

"If it hasn't affected you, you're very lucky - because I'm seeing it across the board."

- Published9 January 2019

- Published30 November 2018

- Published7 August 2019

- Published14 May 2018