Contaminated blood inquiry: Extra money 'a matter for the assembly'

- Published

Messages left in memory of those affected by contaminated blood product at the Infected Blood inquiry in Belfast

Any decision over more financial aid for victims of the contaminated blood scandal should be a matter for the assembly, an inquiry has heard.

The Infected Blood Inquiry is looking into what has been called "the worst treatment scandal" in NHS history.

Some 4,800 people with haemophilia were infected with hepatitis C or HIV in the 1970s and 1980s.

A letter from Northern Ireland Secretary Karen Bradley about financial support was read out on Thursday.

She was responding to an email from an anonymous witness to the inquiry.

There have been complaints that victims of the contaminated blood scandal in England and Scotland are receiving more financial help than those in Wales and Northern Ireland.

Witness I asked Mrs Bradley about the extra money which has been received by victims in England, and asked if Northern Ireland could follow suit.

The witness told the inquiry he had received a response on Thursday.

Mrs Bradley said: "It is only right that those whose lives have been blighted should receive the care and assistance they need.

"Of course the best means of supporting victims in Northern Ireland is via a functioning assembly in which locally elected ministers can speak up and act on their behalf.

"That is why securing a successful outcome to the talks process is my absolute priority."

'Held back'

Responding, Witness I said: "We're just stalled again and we will just be held back and used to try to get politicians with no relevance to this inquiry back around a table.

"I don't think Stormont has anything to do with this. I think the fact the scheme is already in place, it just takes a civil servant or herself [Mrs Bradley] to sign a page and uplift it [the financial assistance] to mirror England."

In a statement, the Department of Health said: "Payments to beneficiaries in Northern Ireland were at similar levels to England's scheme until the recent announcement regarding an uplift for English beneficiaries on the 30 April 2019.

"There were no extra resources for Northern Ireland as a result of the English announcement.

"The department is considering the Northern Ireland position in light of these recent developments and will participate in discussions with the other UK regions in forthcoming weeks."

Northern Ireland has been without a devolved power-sharing government for more than two-and-a-half years, after the DUP and Sinn Féin split in a bitter row.

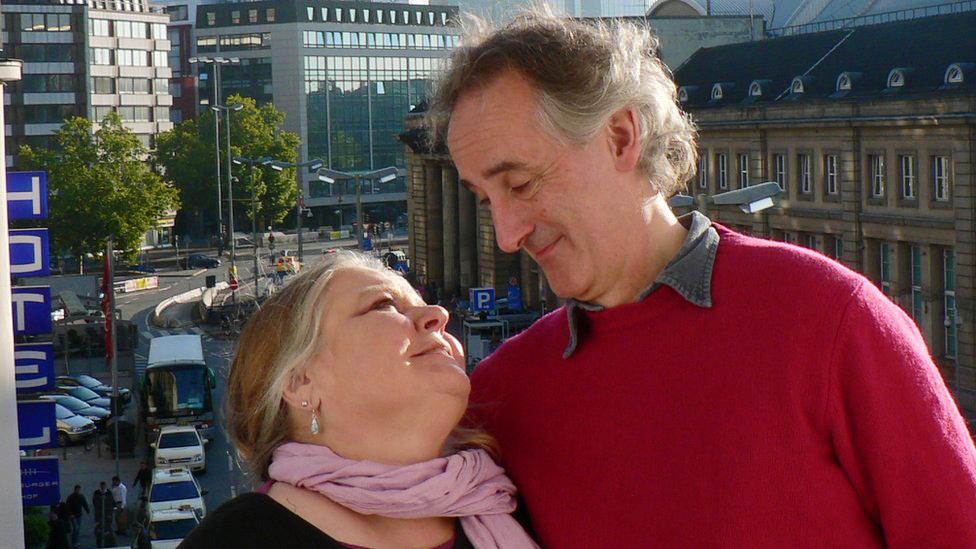

Nigel and Simon Hamilton, who are twin brothers, have given evidence at the infected blood inquiry in Belfast this week

The inquiry is looking at why thousands of people with haemophilia were infected with hepatitis C or HIV in the 1970s and 1980s.

With allegations of a cover-up, no-one in government or the NHS has been held to account.

Some people have waited 30 years for a full public inquiry.

Earlier on Thursday, a man told the inquiry he has "gone through a process of hell" as a result of receiving contaminated blood.

Nigel Hamilton, 58, gave evidence a day after his twin brother, Simon.

Both men have haemophilia and contracted hepatitis C as a result of receiving contaminated blood products.

Nigel Hamilton received contaminated blood during an operation in the Royal Victoria Hospital in Belfast in the 1970s.

He said he was often starved of information and was only told he had contracted the virus during a routine visit to a hospital in England, despite the Belfast Health Trust knowing about the diagnosis some 12 months previously.

"As you can imagine the very first experience of hearing this left me in total shock," he said.

He said sufferers across the UK need closure.

Witnesses from Northern Ireland are speaking at the inquiry this week

In his testimony he recounted a life which has experienced two marriage breakdowns, cancer and the loss of his career.

He told the inquiry his life had been "destroyed" and referred to the blood scandal as a "national disaster".

While he said he does not expect to get justice, he hoped the inquiry would help him and thousands of others to find "closure".

Addressing the inquiry chairman, Sir Brian Langstaff, he said: "We will never get justice. Through you sir, and your good judgement, we will get closure."

His brother, Simon, gave evidence on Wednesday and said he felt like he was the "last to know" about his own case.

What is the scandal about?

About 5,000 people with haemophilia and other bleeding disorders are believed to have been infected with HIV and hepatitis viruses over a period of more than 20 years.

That was because they were injected with blood products used to help their blood clot.

It was a treatment introduced in the early 1970s - before then, patients faced lengthy stays in hospital to have transfusions, even for minor injuries.

The UK was struggling to keep up with demand for the treatment - known as clotting agent Factor VIII - and so supplies were imported from the US.

But much of the human blood plasma used to make the product came from donors such as prison inmates, who sold their blood.

Factor VIII was imported from the US in the 1970s and 1980s

The blood products were made by pooling plasma from up to 40,000 donors and concentrating it.

People who had blood transfusions after an operation or childbirth were also exposed to the contaminated blood - as many as 30,000 people may have been infected.

By the mid-1980s, the products started to be heat treated to kill the viruses.

But questions remain about how much was known before that and why some contaminated products remained in circulation.

Screening of blood products began in 1991.

By the late 1990s, synthetic treatments for haemophilia became available, removing the infection risk.

- Published22 May 2019

- Published21 May 2019

- Published20 May 2019

- Published30 April 2019

- Published24 September 2018

- Published30 April 2019