Spanish flu: How Belfast newspapers reported 1918 pandemic

- Published

The Spanish flu pandemic of 1918 is believed to have infected about a third of the world's population

Just over a century ago, a highly-infectious disease swept around the world causing major public health problems in many countries, including Ireland.

Spanish flu was a pandemic that peaked in 1918, heaping more death and misery on populations already devastated by World War One.

It is believed to have infected about a third of the global population and caused about 50 million deaths worldwide.

That final death toll is disputed and very difficult to verify, but in Ireland alone Spanish flu is estimated to have caused or contributed to 23,000 deaths.

Despite its name, Spanish flu did not originate in Spain. The label stuck because Spanish newspapers were the first to report the outbreak.

Spain was a neutral nation during World War One, so its journalists did not face the same censorship as those working in countries involved in the conflict.

The deadly flu hit pre-partition Ireland in three waves, according to historian and author Ida Milne who has spent years researching the impact of Spanish flu across the island.

Belfast was hardest hit in the first wave in May 1918, she explained, whereas the flu peaked in many southern areas in the autumn.

So how did Belfast newspapers report what turned out to be the worst pandemic of the 20th Century?

Belfast City Hall in 1917 - a year before Spanish flu almost brought the city's tram system to a halt

With the benefit of 20/20 hindsight, given what we now know about the devastating impact of Spanish flu, it received relatively sparse coverage in Belfast's dailies in 1918.

It should be pointed out that in the dying days of World War One, editors were rarely, if ever, stuck for dramatic headlines.

As the Allies advanced to victory, Belfast's newspapers were filled day after day with incredibly detailed reports from battlefields in France, Germany, Italy, Palestine and further afield.

The first substantial mention of a problem developing on their own doorstep was on 11 June 1918.

The Belfast Evening Telegraph and the News Letter each devote just a few column inches to an "influenza epidemic" in Belfast.

The News Letter reported that about a dozen schools were closed and several businesses were affected due to the number of workers who had fallen ill.

But editors were clearly concerned about being accused of scaremongering.

"There is no reason for the general public to become unduly alarmed, and the rumours currently in the city may be accepted with the proverbial grain of salt," the Telegraph advised.

Keen to keep things in perspective, the paper stated the general view from the medical profession was "against the outbreak being any serious disease".

Ms Milne, who lectures on European history at Carlow College, is not surprised that the specific threat was not immediately obvious in 1918.

'So used to death'

Death from a range of infectious diseases like tuberculosis, bronchitis, measles or scarlet fever were a common occurrence at the time, she explained.

"TB was a massive killer... and at those stages they had no antibiotics to counter bacterial pneumonia, so there were thousands of deaths on the island from that," she said.

"The background level of disease was so high that I think in some ways Spanish flu wasn't recognised within communities for what it was - with the same lens that we look back today and see that it was a big disease event - because they were so used to death within families."

Inside a week however, the Telegraph declared that "Berlin has Belfast's epidemic" and stated the disease has become known as "Spanish influenza".

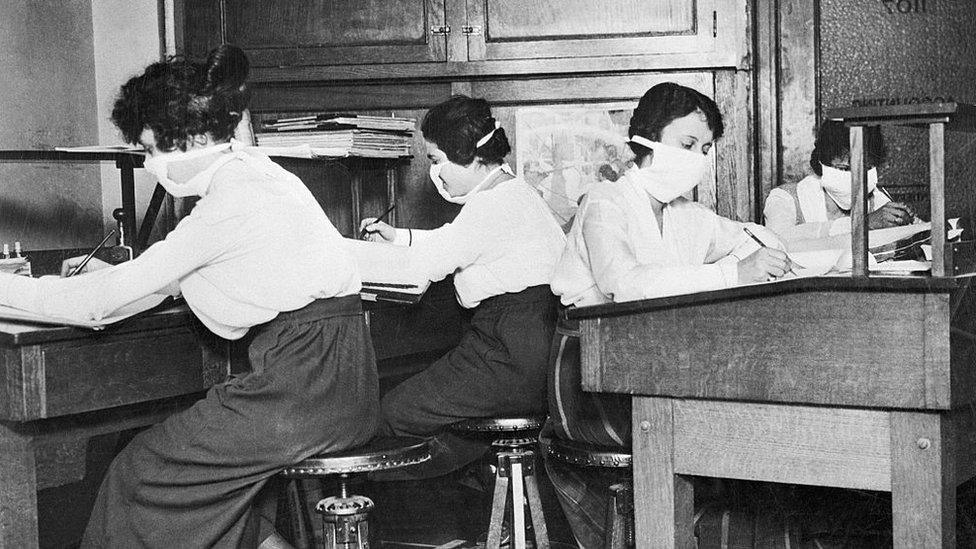

Spanish flu affected up to 40% of the US Army and Navy, many of whom were sent to Ireland during WW1 (Colorado hospital)

By late June, the Irish News reported that thousands of Belfast's workers are laid up with flu, affecting the operation of the city's shipyards and trams.

The paper said chemist shops were being "literally besieged" and called on the public health authorities to issue instructions on how to deal with the illness.

Notably, the Irish News kept a close track on the monthly mortality rate from all causes across major Irish cities, and is clearly surprised when deaths are higher in Belfast than Dublin.

"It is a most remarkable fact that no less than 40 deaths from pneumonia occurred in Belfast. From the same cause in Dublin there were only six," the paper observed.

When the second wave of Spanish flu hit in autumn 1918, editors arguably had a better idea of what they were dealing with.

The Telegraph reported epidemics in Capetown, London and Dublin, describing the London death rate as "alarming" and warning that Dublin's hospitals were so congested there was no space for accident victims.

There were 50 burials in Dublin's Glasnevin Cemetery on 8 November alone, described as a "record" number in one day.

Spanish flu struck Dublin while the city was still trying rebuild after the 1916 Easter Rising

Spanish flu was particularly unusual because it claimed the lives of so many young adults who are not normally in categories considered vulnerable to flu.

A few examples of such cases appear intermittently in Belfast's papers - the deaths of a trainee nurse at the city's Union Workhouse and a new mother from Larne who "dropped dead" three weeks after giving birth.

The "sudden demise" of a Carrickfergus bank official is also reported - the Telegraph noted he was at his desk on Tuesday but had succumbed to flu by the following Saturday.

By early November, all schools in Belfast were closed and public entertainment was cancelled in a bid to stop the flu spreading.

These emergency measures were announced not in a headline, but via newspaper notices from the Public Heath Office.

To be fair, though, the measures were introduced days before the Armistice on 11 November, when the only story in town was the end of World War One.

Armistice celebrations were held in many towns and cities, including this one in England in November 1918

But then large public gatherings to celebrate victory exacerbated the flu outbreak.

"About a week to a fortnight later, there is a spike in flu and pneumonia deaths because of this movement of people," said Ms Milne.

Given its relative lack of prominence in Belfast news reports, the impact of Spanish flu on everyday life was often more obvious from adverts and public notices.

Bizarre and sometimes comical claims about flu prevention and so-called cures are regularly featured.

Belfast's Alhambra Theatre paid for an ad to reassure patrons it had been sprayed and disinfected. It clamed the theatre was now "influenza-proof".

The Picture House on Royal Avenue declared itself the "healthiest place in town" after spending thousands of pounds on a new ventilation system.

Veno's Lightning Cough Cure boasted it was not only a remedy for Spanish flu but also for those suffering from gas - not digestive gas but the chemical weapon used by the German army.

In the current coronavirus pandemic, stocks of hand sanitiser and face masks were the first to run low, but a century ago the must-have health protection item was beef tea.

Bovril was in such short supply in 1918 that the firm took out large adverts to apologise, explaining bottles could not be manufactured fast enough to meet demand.

The deadliest flu pandemic in modern history undoubtedly left its mark on the citizens of Belfast.

But, overshadowed by the drama and suffering of Great War, it rarely made headline news.

- Published24 November 2018