Tory leadership: Who gets to choose the UK's next prime minister?

- Published

Who are the Conservative Party members?

Conservative MPs may have whittled the contenders in the leadership race down to the final two - but it will not be politicians who will decide who gets to be the next prime minister.

Instead it will be the party's grassroots members who will decide which of Jeremy Hunt and Boris Johnson gets to succeed Theresa May.

They will do so in a postal ballot, with the winner announced in the week beginning 22 July.

In other words, it is members of the public - those who pay £25 a year to join the Conservative Party - who get the final say on who leads the country.

There will not be a general election because the party is already in power.

So, who are the Conservative Party's members and what do they think on key issues, not least, of course, Brexit?

The Conservative Party membership is currently thought to be around 160,000, external - a rise of more than 30,000 in the past 12 months.

The last time official figures were released was in March 2018, when they put the figure at 124,000.

That is way down on the peak of nearly 3 million that the party boasted in the early 1950s.

The Tories have far fewer members than the Labour Party.

Even if we assume that Labour's membership has fallen from the late 2017 peak of more than 550,000, it still has a huge advantage over the Conservatives when it comes to campaigning on the ground.

Right now, however, none of that matters as much as the fact that those 160,000 or so rank-and-file members of the Conservative Party have a crucial role.

They are going to be choosing the next prime minister of a country of over 65 million people - something which has never happened before.

From studies of the 124,000 members that the party had in 2018, we know quite a lot about who they are and their beliefs.

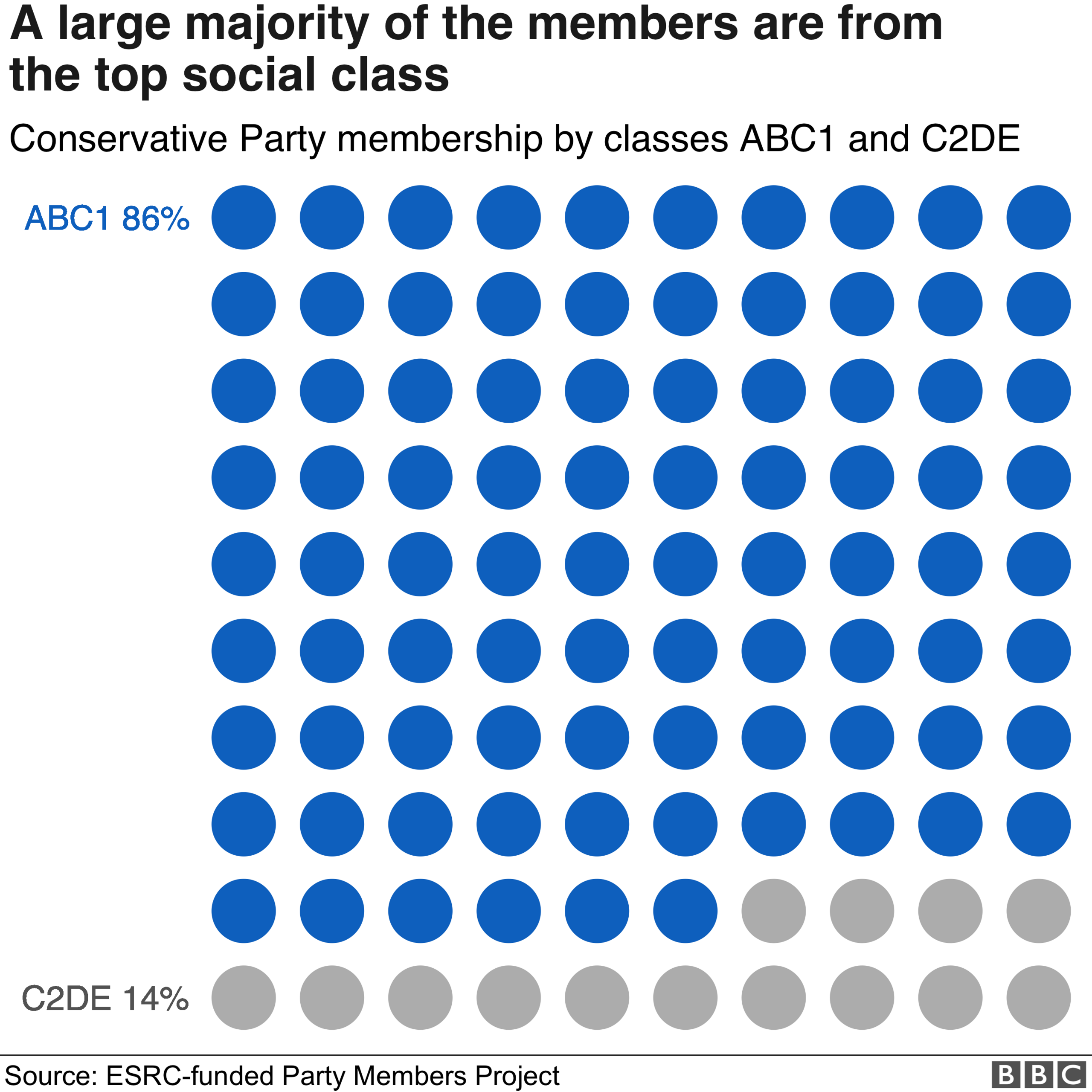

Most members of most parties in the UK are pretty middle-class.

But Conservative Party members are the most middle-class of all: some 86% of them fall into the ABC1 category used by market researchers to describe the top social grade.

Around a quarter of them are, or were, self-employed and nearly half of them work, or used to, in the private sector.

Nearly four out of 10 put their annual income at over £30,000, and one in 20 put it at over £100,000. As such, Tory members are considerably better-off than most voters and, indeed, the members of other parties.

On the other hand, the fact that 97% of Conservative Party members are white doesn't do much to distinguish them from their counterparts in other parties.

It does inevitably mean, however, that ethnic minorities, who make up well over 10% of British people, are heavily under-represented in the Tory rank and file.

So, too, are women. Other parties - notably Labour and the Greens, but also the SNP - now come close to gender balance, but seven out of 10 Conservative members are male.

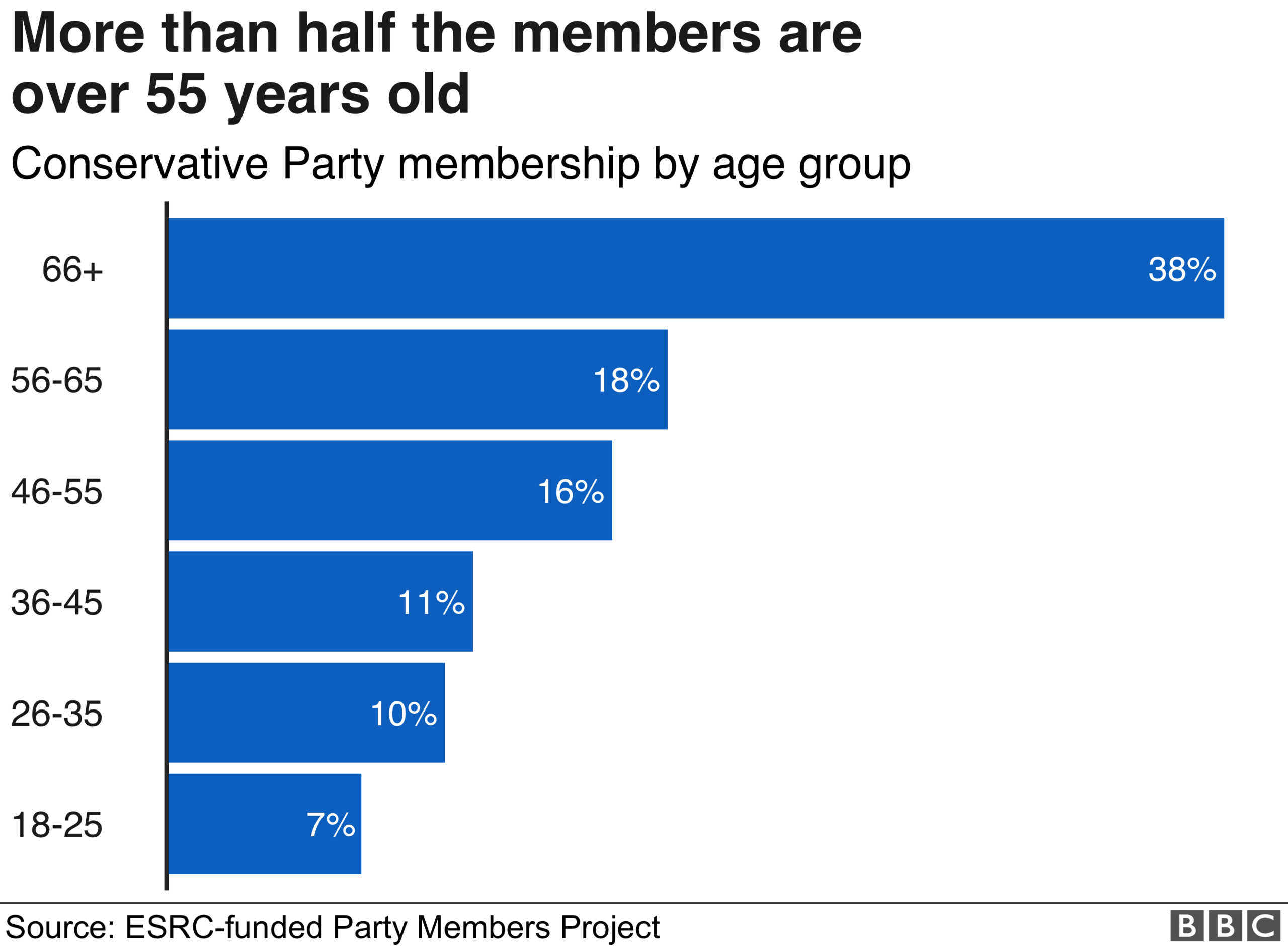

Tory members are also older than the members of most other parties. True, their average age may "only" be 57, but this disguises the fact that four out of 10 are over 65.

They are concentrated in the southern half of England. Nearly 60% of Tory members live in London, the east, south-east and south-west.

So much for demography and geography. What about ideology?

Well, not surprisingly, Tory Party members are more right-wing than the population as a whole.

On a scale where zero represents very left-wing and 10 very right-wing, the average voter places themselves at the centre point. The average Conservative Party member places themselves at 7.6.

Certainly, grassroots Tories are socially conservative.

Three-quarters of them believe, for instance, that young people today don't have enough respect for traditional values. Nearly six out of 10 support the death penalty.

They are also conventionally right-wing on some aspects of economic policy.

For example, only 15% of them believe that government should redistribute income from the better-off to those who are less well-off.

But on other issues they hold views that may be more unexpected.

A third of Tory rank-and-file members believe that ordinary working people do not get their fair share of the nation's wealth and that there is one law for the rich and one for the poor.

About half believe that big business takes advantage of ordinary people.

Interestingly, they have also cooled on austerity. In the summer of 2015, some 55% said government spending cuts hadn't gone far enough, but two years later that had fallen to 28%.

Commons leader Andrea Leadsom quit amid a backlash against Brexit plans

What Tory members haven't cooled on, however, is Brexit.

Indeed, since we started tracking them in 2015, they've hardened their position.

It is clear that they are not supporters of the deal negotiated by Theresa May.

In fact, it is now the case that fully two-thirds of them back a no-deal Brexit - an outcome supported by only a quarter of voters as a whole.

Nor are they in the least bit keen on the idea of letting the public have another say on the UK's EU membership.

Some 84% of them oppose the idea of a new referendum on the issue.

In short, the grassroots aren't simply sceptical on Europe; they can't wait to leave, whatever that might take.

Furthermore, a breakdown of YouGov polling data suggests that the 30,000 or so members who have joined in the past year are even more likely to be pro-Brexit.

This, then, is the Conservative Party electorate.

And those MPs hoping to succeed Mrs May will need to pitch their promises accordingly.

About this piece

This analysis piece was commissioned by the BBC from experts working for an outside organisation.

Tim Bale is Professor of Politics at Queen Mary University of London, external.

Edited by Duncan Walker

- Published20 June 2019

- Published23 July 2019