Hong Kong protests: Jeremy Hunt 'keeping options open' over China

- Published

- comments

The UK foreign secretary has continued to warn China it could face "serious consequences" over its treatment of protesters in Hong Kong.

Jeremy Hunt told the BBC he was keeping his options open over how the UK could respond, and refused to rule out sanctions.

A group of activists occupied Hong Kong's parliament on Monday over a controversial extradition bill.

China warned the UK not to "interfere in its domestic affairs".

Mr Hunt said he would not discuss any potential consequences "because you don't want to provoke the very situation you are trying to avoid".

"Of course you keep your options open," he added, insisting the UK would not just "gulp and move on" if China cracks down on protesters in the former British colony.

Mr Hunt said he "condemned all violence" but warned the Chinese government not to respond to the protests "by repression".

Hong Kong was a British colony for more than 150 years, but it was returned to China in 1997 after a treaty was signed by the two countries.

The 1984 treaty guaranteed a level of economic autonomy and personal freedoms not permitted on the mainland.

Demonstrators argue that a piece of legislation introduced by the city's pro-Beijing leader would make it easier to transfer people to face trial in China.

Mr Hunt reiterated that China must honour Hong Kong's high level of autonomy from Beijing.

"The heart of people's concerns has been that very precious thing that Hong Kong has had, which is an independent judicial system," Mr Hunt told Radio 4's Today programme.

"The United Kingdom views this situation very, very seriously," he added.

China's ambassador was summoned to the Foreign Office on Wednesday following "unacceptable and inaccurate" remarks.

Liu Xiaoming said relations between China and the UK had been "damaged" by comments by Mr Hunt and others backing the demonstrators' actions.

He said those who illegally occupied the Legislative Council building and raised the colonial-era British flag should be "condemned as law breakers".

A protester covered a Hong Kong emblem with a British colonial flag in a government building on Monday

He added that it was "hypocritical" of UK politicians to criticise the lack of democracy and civil rights in Hong Kong when, under British rule, there had been no elections nor right to protest.

Analysis: Will the war of words endanger relations?

By James Landale, BBC diplomatic correspondent

Britain's relations with China are at a low ebb. The question now is whether the damage is lasting.

China appears determined to use the Hong Kong protests as an opportunity to push back against what it sees as Britain's illegitimate interference in its former colony.

But equally Britain seems determined not to be bullied by China.

Mr Hunt says the UK has every right to defend a treaty it signed with China in 1984 guaranteeing Hong Kong's freedoms and relative autonomy.

The foreign secretary had no option but to summon the Chinese ambassador to London for a diplomatic dressing down.

The danger is that this war of words infects the wider relationship and endangers Britain's strategic trading interest with China, something that will only become more important after Brexit.

So Mr Hunt threatens "serious consequences" if China fails to honour the so-called Joint Declaration treaty.

But he remains tight-lipped about what that might mean, not just because the UK has few diplomatic or economic cards it might wish to play, but also because he does not want to provoke a subsequent clash that might damage Sino-British relations even further.

In response to accusations he had sided with the protesters, Mr Hunt said: "I was not supporting the violence, what I was saying is the way to deal with that violence is not by repression."

"It is by understanding the root causes of the concerns of the demonstrators - that freedoms that they have had for their whole life could be about to be undermined by this new extradition law," he added.

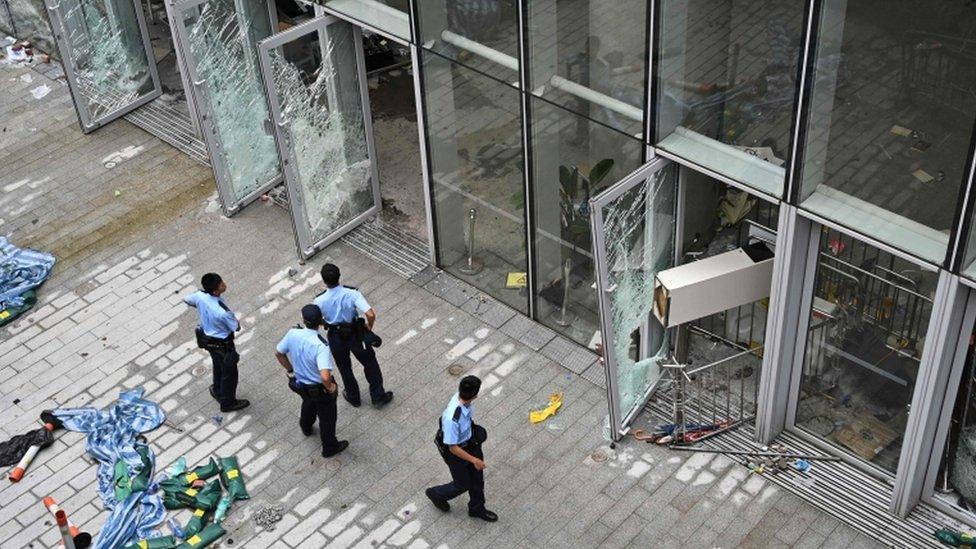

Masked protesters stormed the Legislative Council building in Hong Kong on Monday

Victor Gao, vice-president of the Centre for China and Globalisation in Beijing, called Monday's occupation of parliament "anarchism", adding "this is to be protested and to be condemned by any government leader with any level of conscience".

Mr Gao urged the UK to condemn the violence. He said the "crux of the matter" was "the UK no longer has a say in [how] Hong Kong should be run and managed".

In 1984, the Joint Declaration, signed by Margaret Thatcher and the then Chinese Premier Zhao Ziyang, set out how the rights of Hong Kong citizens should be protected in the territory's Basic Law under Chinese rule.

Hong Kong has its own legal system, and rights such as freedom of assembly and free speech are protected

Since 1997, Hong Kong has been run by China under the principle of "one country, two systems".

Mr Hunt said: "It is very important that the 'one country, two systems' approach is honoured."

The foreign secretary would not detail what consequences China might face if it did not honour the treaty, but said the UK had "always defended the values we believe in".

- Published21 May 2020

- Published20 July 2020