Analysis: Steel and the EU referendum

- Published

The EU referendum is coming along at the same time as the British steel industry is at a crossroads.

The process for the sale of Tata Steel UK's operations is under way and inevitably the role of the European Union in the industry's future has been an issue for both sides in the campaign.

STEEL AND EUROPE - A LONG HISTORY

British industry was not part of the original European steel community in the 1950s

Steel has been at the heart of the European project since it was first conceived more than 60 years ago.

The European Coal and Steel Community had six members - France, West Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg, while Britain decided against joining.

Its aim was to prevent another European war but from the beginning there was always a drive for closer integration and the common market was established six years later.

That developed into the European Union and both sides of the EU referendum argument have been highlighting its current role in the UK's steel crisis.

The EU wants to avoid 'subsidy races' between nations

STATE AID

The EU Commission has what it calls "strict safeguards" against state aid to rescue and restructure steel companies in trouble.

It wants to avoid "harmful subsidy races" between countries - if state aid is uncontrolled in one EU country it argues it can put jobs at risk in others.

State aid rules have certainly prevented the UK and Welsh Governments from helping the steel industry with business rates.

But the rules do allow governments to support environmental research or relieve energy costs of steel companies.

The outgoing Welsh Business Minister Edwina Hart admitted last month the rules were "rather inflexible" and had "driven me mad".

She said she believed there needed to be more flexibility "because the steel industry, since the rules were set up, has changed dramatically across the globe, and particularly in Europe."

However, successive UK governments have supported state aid rules in principle because they prevent other EU nations from subsidising their industries and damaging companies and jobs in the UK.

Supporters of state aid rules argue it is not an efficient use of taxpayers' money to subsidise industries that would not otherwise survive.

Such rules were swept away to support banks during the financial crisis.

TARIFFS

Steel pipes in south western China

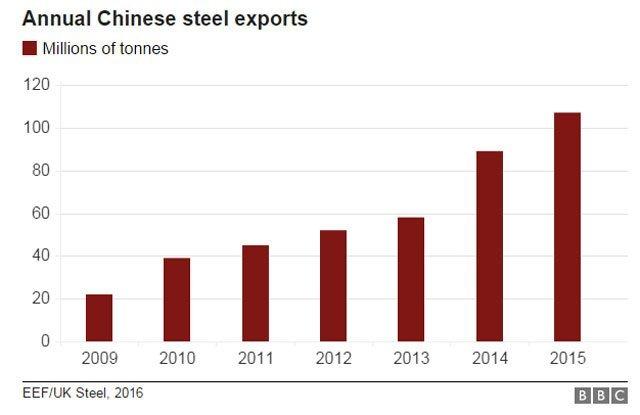

Unions and steel makers in the UK have been raising concerns for years that cheap steel from China has been flooding into Europe.

They have been calling for the EU to impose tariffs on Chinese steel which they claim is being sold below the cost of producing it, also known as "dumping".

The European Commission has already taken action against some products but has been accused of acting too slowly.

The tariffs imposed have also been criticised as being too low, particularly in comparison to those the United States has put on Chinese steel of up to 266%.

Steelworkers from south Wales called for a level playing field while Jyrki Katainen, European Commission vice president, said quite a lot was being done to help

For those who want to leave the EU this is evidence that slow action by the European Commission has made the UK's steel crisis worse.

However, the UK government has been accused of being the "ringleader" in efforts to keep tariffs at a lower level - the so-called lesser-duty rule.

Ministers have denied this, but have also warned that getting into a trade dispute with China, including tit-for-tat tariffs, could harm other industries like the automotive sector.

There have been fears this could lead to protectionism in Europe , externaland instead there needs to be a balance.

An argument for remaining is that, as a bigger trading block, the EU has more influence with China than the UK would have if outside.

When George Bush imposed tariffs on steel in 2002, it was the threat to escalate it to other products, including Florida oranges, by the European Union that led to them being abolished.

CHINA AND THE MARKET ECONOMY

Energy Minister Andrea Leadsom was questioned by Welsh MPs last week

There is currently a debate about whether Europe should now recognise China as a market economy - as part of its place in world trade.

It is argued one of the consequences of this is it could make it much more difficult for the EU to impose tariffs on Chinese companies for dumping.

It was brought up again at the Commons' Welsh Affairs Committee inquiry into the steel industry on Monday.

Energy Minister Andrea Leadsom said it was "absolute rubbish" to suggest that the UK government had prioritised China's interests in terms of steel.

She had been responding to a question from Welsh MP Liz Saville Roberts about Conservative MEPs voting in favour of giving China market economy status.

ENVIRONMENTAL TAXES

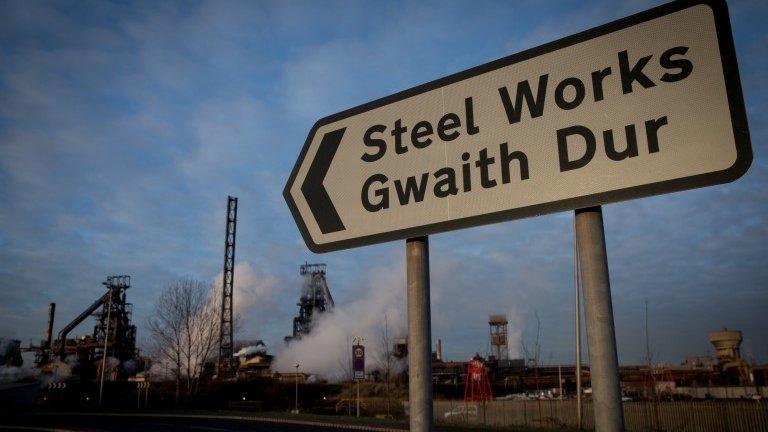

Port Talbot steelworks uses as much energy as all the homes and businesses in the city of Swansea along the coast

Long before UK steelmakers and unions were objecting to Chinese imports, they were raising concerns about the high energy costs here making production uncompetitive with some other EU countries.

They called for a level playing field.

The coalition government went to the EU to get an agreement to help with the costs of high energy using industries including steel.

This took some negotiation and has only recently come into force.

Critics of the EU say this shows the length of time it takes to get a decision and how powers are in the hands of the Commission rather than UK ministers.

Supporters would argue it was the UK government which introduced these environmental taxes in the first place, making businesses bills higher than in some other parts of the EU.

- Published30 December 2020

- Published9 March 2016

- Published18 May 2016

- Published3 March 2016

- Published25 April 2016

- Published19 May 2016

- Published26 April 2016

- Published30 March 2016

- Published19 January 2016

- Published10 August 2012

- Published4 April 2016