The patients getting hospital treatment at home

- Published

Cecilia Liddel, pictured with her daughter, did not want to return to hospital after an infection and said being treated at home was the "best thing"

A service that brings hospital-level treatment to patients in their own homes is gradually being rolled out across Scotland.

Hospital at Home sees teams of specialists travel to patients who would otherwise receive inpatient care.

At a time of hospital bed shortages, the scheme taps into an "endless number of beds" available in patients' homes.

But it does not solve the problem of shortages of clinicians within the NHS.

Scotland is one of many countries developing these alternatives to inpatient care for an aging population.

There are currently 310 of these "virtual beds" across the country, the equivalent capacity of a hospital such as St John's in Livingston or University Hospital Ayr.

Multidisciplinary teams of healthcare professionals provide the same care they would give in hospital for short acute illness and provide the same urgent access to diagnostics people would have as in-patients.

Midlothian was one of the health boards to pioneer the service almost a decade ago and now has capacity for 60 patients each month.

Cecilia Liddel from Dalkeith, pictured above, is one of them.

The 84-year-old was offered Hospital at Home after an infection she contracted at the start of the year left her hardly able to walk or speak.

She had no appetite and having lost a stone (6.4kg) in weight, it looked likely she would end up back on a ward.

She told BBC Scotland that Hospital at Home was "the best thing" for elderly people like herself, adding: "It was a big deal because I didn't like the hospital."

Her daughter Cecilia Howarth said: "At that age, I think there is that fear that you are just not going to come back out.

"That brings on a lot of anxiety and with the illness it was just too much."

Easing pressure on hospitals

Last May, when there were an estimated 275 beds provided by Hospital at Home services, the Scottish government announced an extra £3.6m in funding with the as-yet unfulfilled ambition of doubling the number of virtual beds, external by the end of 2022.

While the services are funded by health boards, direct government funding has been used to initially develop or expand the schemes.

Most health boards now have Hospital at Home capacity, with NHS Highland and NHS Borders launching pilots in the past couple of months.

According to Healthcare Improvement Scotland, external, NHS Dumfries and Galloway and NHS Shetland are the only health boards currently without the service.

Eligible patients include those with conditions such as pneumonia, urinary sepsis and pulmonary embolism.

It is designed to be a short-term intervention, with most patients treated for five to six days. Doctors say that similar treatment in hospital could be expected to result in an average stay of 20 to 40 days.

It is hoped the service will help ease pressure on hospitals that are already stretched.

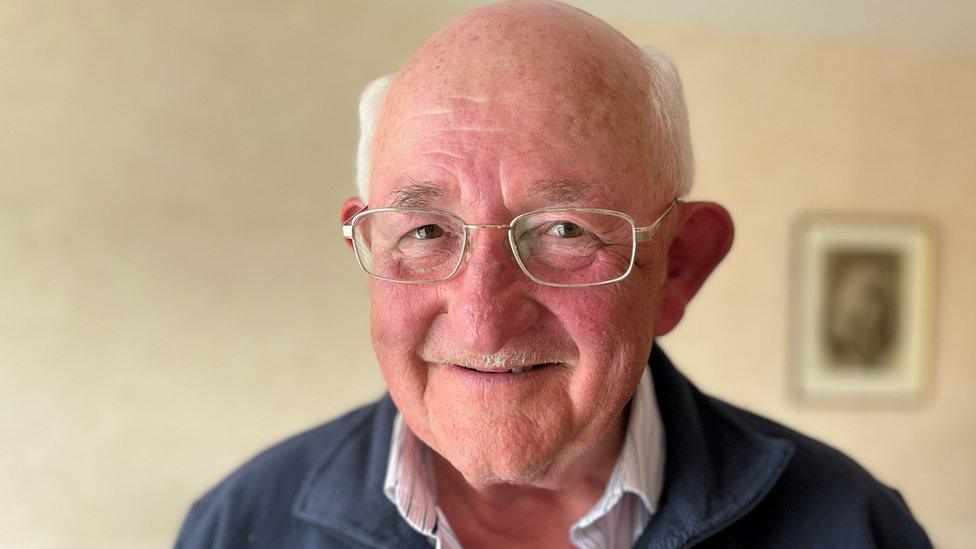

Former shepherd Malcolm Hutchison said being at home to recuperate from Covid was giving him "a lift each day"

Malcolm Hutchison, 91, from Roslin in Midlothian, lived a healthy life working as a shepherd with very little time spent in hospital until he got Covid.

He said he did not expect to survive the virus.

"Who knows when I would've got out of hospital," he said. "A week? A month? But being home is giving me a lift each day."

The service is not just about home comforts - longer stays in hospital can lead to increased frailty in older patients.

By avoiding a hospital stay, vulnerable patients can also keep existing agreements for carers visiting their home to help with essential needs such as washing, eating and taking medication.

Losing their care package can lead to delays getting home while new arrangements are put in place.

Cost of community care

In the final few months of last year, the number of patients delayed in hospital reached a record high.

Almost one in six of Scotland's hospital beds were occupied by patients who could be discharged if other care could be provided at home or in a care home.

The numbers became extremely high following the Covid pandemic and hospitals are struggling to get the numbers down.

The latest figures from Public Health Scotland show that in March an average of 1,743 beds were taken each day, external by patients who no longer had a clinical need to remain in hospital.

Grace Cowan, who is the head of primary care and older people's services at Midlothian Health and Social Care Partnership, said providing more care in the community came at a cost.

"In the current climate that's not something we've got - an abundance of money - we don't have a pot of gold somewhere," she said.

"So we have to look at how we best deliver our services in different ways to build that capacity and build that virtual capacity in the community."

In Midlothian, where Hospital at Home capacity recently doubled to about 60 monthly patients, most of Dr Lizzi Boyce's patients manage to avoid hospital, with only about 10% to 15% needing to be admitted.

Dr Lizzi Boyce said longer-term financial commitment was needed to recruit the staff needed for Hospital at Home

The team's clinical lead said: "It's not right for everybody and I think it's really important to recognise that Hospital at Home is one of many services that work in the community to provide support.

"Patients will still need hospital level care at times."

But Dr Boyce added: "If we are seeing 60 patients within a month, that is 60 patients who haven't turned up at the front door and haven't been stuck in A&E."

She welcomed the short-term funding from the Scottish government in recent years but said a longer-term financial commitment was needed so they can employ permanent members of staff and not just offer short-term contracts.

"Ultimately it's about more staff because there's an endless number of beds available out there in patients' homes," she said.

"But we do need the staff with the skills to be able to deliver those services."

'Yearning to get home'

Colin McIsaac said a busy hospital ward was not a good environment to get better

Colin McIsaac, 73, was relieved to be treated at home. He has had a number of overnight stays in hospital in the past and not found it a pleasant experience.

He said: "There were people with problems in the middle of the night. It's a constant go. To me, it is not a good environment to try and get better.

"I think most people who are in hospital are probably yearning to get home."

Sharon Dempsey, an advanced nurse practitioner, is one member of the team that treated Mr McIsaac.

Advanced nurse practitioner Sharon Dempsey provides hospital-level care in patients' homes

"Colin is quite typical of our patients, usually someone with breathlessness, heart failure, infections, exacerbations," she said.

"If we couldn't deliver the care Colin needs, he would have to be in hospital."

Related topics

- Published19 January 2023

- Published16 January 2023

- Published9 January 2023

- Published1 November 2022