Duke of Cumberland's Stone: The rock with a hard place in history

- Published

After Culloden, the Duke of Cumberland's Stone, a relic of the last Ice Age, became forever linked to the battle's bogeyman. But is it deserving of the association and the abuse it has taken over many years?

On 16 April 1746, William Augustus Hanover, the Duke of Cumberland, defeated Bonnie Prince Charlie and his Jacobite army at Culloden.

Cumberland's victory was followed by a campaign to crush further Jacobite opposition to the government and the Crown.

Jacobite supporters were executed, others were imprisoned and the homes of sympathisers in the Highlands were ransacked and burned.

The actions led to the duke being nicknamed the Butcher.

While Cumberland is long gone, a more permanent feature of the battlefield landscape continues to be a target for outpourings of anger by some at what happened 267 years ago.

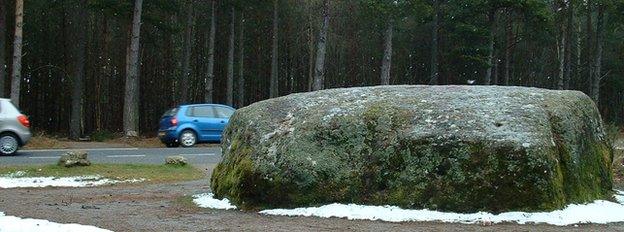

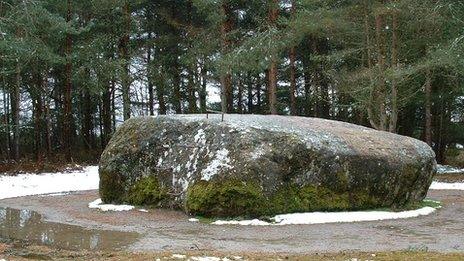

Sitting just off the B9006 Culloden to Nairn road lies Cumberland's Stone, a big smooth lump of rock.

The boulder is covered in moss and blue-green lichen. It sits in a little clearing on the edge of a small conifer plantation. In a corner of the site, a discarded juice bottle and snacks wrappers float in a muddy puddle.

Stories tell of the Duke of Cumberland having breakfast, or his lunch, on the table-flat top of the boulder on the day of the battle. It has also been said that he stood on the stone to better survey the course of the fighting.

The words "Cumberland's Stone" are thought to have been carved into the rock in 1881, and at some point four metal rungs were hammered into it so people could more easily climb up on to it.

In more recent times the boulder has been sprayed with graffiti and a fire was even set against it in a supposed attempt to cause damage to it.

But is the stone deserving of the abuse?

Pudding stone

If it was not for the last Ice Age, the boulder would not be there in the first place.

The boulder is a glacial feature known as an erratic, meaning it is of a rock type that is different from the bedrock on which it sits.

Members of the Inverness Scientific Society and Field Club made a visit to Cumberland's Stone in the 1870s.

They determined the boulder to be a large block of conglomerate, also known as pudding stone. The bedrock beneath it is also conglomerate, but of a different type.

Society members suggested Cumberland's Stone matched the geology of Stratherrick, external, which lies almost 20 miles (32km) south of Inverness.

The rock was torn from the ground at Stratherrick as a huge ice sheet crept out of the west towards the Moray Firth coast.

The rock's jagged edges were smoothed as the stone slowly rolled and shifted within the ice. It was plonked at Culloden 16,000 years ago when the ice eventually melted.

The stone is a clue to the Highlands' Ice Age past

Prof Colin Ballantyne, of University of St Andrews' School of Geography and Geosciences, said erratic rocks such as Cumberland's Stone help scientists to understand glacial geology.

He said: "Erratic boulders like Cumberland's Stone are used by geomorphologists to trace the former directions of movement of the last ice sheet.

"This ice sheet reached its maximum dimensions about 22,000 years ago. At that time the ice sheet covered all of Scotland, including the highest mountain summits, extended eastwards to join the Scandinavian Ice Sheet in the North Sea basin and extended westwards to the edge of the Continental shelf, about 50km west of St Kilda."

Prof Ballantyne added: "Cumberland's Stone was carried a few tens of kilometres as part of a fast-moving body of ice within the last ice sheet known as the Moray Firth Ice Stream.

"Some erratics have travelled much farther. Erratics from Ailsa Craig in the Firth of Clyde, for example, have been recovered from glacial deposits in Wales."

Paul Lang, a living history re-enactor who has had interest in Culloden since working at the battlefield as a teenager, believes the Culloden stone's notoriety is undeserving.

He recalls how in 1996, on the 250th anniversary of the battle, it was spray painted and a small fire was set against leaving scorch marks on the stone.

"To me the Cumberland connection is a myth," he said.

"Cumberland at the time was not the most mobile man. He was carrying injuries. The idea of him climbing up on to the stone to have his lunch seems crazy."

Mr Lang said the duke was recorded to have been on horseback during the battle and took up a position between the first and second lines of his regiments.

"That's a good 400 to 500 metres from the frontline," he said, adding: "The stone is too far away for Cumberland to have been able to see what was going on during the battle."

'Party guy'

Mr Lang said the stone's reputation could be rehabilitated by an older story about its part in bringing together early 18th Century high society lovers Duncan Forbes and Mary Rose, a baron's daughter.

"Duncan Forbes had a reputation for being a boozer and a party guy and the baron was not happy about his daughter seeing him," said Mr Lang.

"The couple are said to have met at a large stone on the edge of Culloden Estate not far from the road to Nairn. Today's road is not far from where the old one ran and the only big stone close by - and on the edge of the estate - is Cumberland's Stone."

After training in law, Forbes married his sweetheart. Mr Lang said: "Duncan Forbes' attitude changed. He became focused on law and was dedicated to his wife, who died 10 years later."

Forbes was law lord at the time of the 1745 Jacobite Rising, holding the title of Lord President. He supported the government and made efforts to convince some clan chiefs not to risk ruin by siding with Bonnie Prince Charlie.

Mr Lang said: "After Culloden, Forbes was saddened by what happened to his fellow Highlanders. He died the following year, some say of a broken heart."

- Published10 April 2013

- Published23 November 2012

- Published24 October 2012

- Published22 April 2011