Post-indyref Scotland: Two years in a changing nation

- Published

Independence supporters are marking the second anniversary of the referendum

Exactly two years have passed since the Scottish independence referendum. What has happened since and how did the 2014 poll help shape future events?

"The UK that Scotland voted to remain within in 2014 does not exist anymore."

It's been one of Nicola Sturgeon's favoured phrases in recent months - inspired by a different referendum, but one with a similarly disappointing overall result for Scotland's first minister.

The SNP leader paints the UK's vote to leave the European Union as the key "material change" which could spark a second independence vote, but it is far from the only thing which has altered in the past two years.

And while some of these changes might have boosted Ms Sturgeon's hopes for an independent Scotland, others may have done quite the opposite.

The SNP surge

The SNP almost wiped their rivals off the map entirely in 2015

They may have lost the independence referendum, but the SNP have gone from strength to electoral strength since.

Scots have spent an inordinate amount of time in polling booths of late, making five trips there across the past three years; and a lot of the time they've been voting SNP.

The Nationalists saw a massive bounce in support through the tail end of 2014, with Yes campaigners swallowing the disappointment of the referendum and signing up as SNP members in their thousands. Following the Brexit vote in June this year, the SNP's membership surpassed 120,000.

Perhaps crucially, the party immediately made a clean break after the referendum by replacing leader and first minister Alex Salmond with his deputy, Nicola Sturgeon.

Nicola Sturgeon went on a stadium tour after becoming SNP leader

Keen to push forward rather than dwell on the result, Ms Sturgeon embarked on a sold-out stadium tour, reflecting popularity more reminiscent of a pop star than a politician.

Her party already had a fairly dominant position in Scottish politics, having secured an unprecedented majority at Holyrood in 2011. But it paled in comparison to the thumping win secured in the 2015 general election.

The SNP won 56 seats; all of the other parties put together won three. Political correspondents desperately thumbed through thesauruses seeking a stronger word than "landslide".

They were already the biggest fish in the pond, but with Ms Sturgeon at the helm the party became an absolute leviathan.

The stadium tour was just the beginning; party conferences and speeches became increasingly slick and frankly presidential, buoyed by a flood of new membership fees.

And while they may have lost that unlikely Holyrood majority in 2016, the SNP were still a country mile ahead of the opposition.

Labour collapse - Tory revival

Ruth Davidson's Tories had a very good night at the Holyrood elections in May

Where did all of those new SNP voters come from? Well, maybe some were former non-voters inspired by the Yes movement. But an awful lot of them were people who used to vote Labour.

In the 2015 election, where Labour lost 40 seats in Scotland, their share of the vote fell by 18%. The Lib Dems also took a battering, their share dropping by 11% with a loss of 10 seats, all hoovered up by the SNP.

But while the SNP trounced the traditional parties of the left, what had long seemed an unlikely revival was beginning on the right.

In the 2016 Holyrood election in particular, Ruth Davidson's Scottish Conservatives sought to characterise the enduring Scottish political debate as Yes vs No, unionists vs nationalists. And it worked.

The Tory strategy played on the idea that people hadn't really moved on from 2014, targeting the 55% of the electorate who voted No by positioning themselves as the hard unionist party, making Labour look relatively soft.

The red share of the vote and subsequent seat count plummeted, while the blue share soared. One or two polls had tentatively suggested the Tories might just pip Labour into second place - in the end they thumped them.

The indyref effect wasn't confined to these parties either. Willie Rennie won raucous applause at a TV election debate with an impassioned plea to "move on" from constitutional matters - only to see his Lib Dems win only five seats.

Meanwhile the independence-backing Greens bounced up from two seats to six - benefiting from a friendly swing from the SNP on the regional list vote.

Leadership

Fortunes have panned out better for some than for others since the referendum

Think of the party and campaign leaders of 2014; Alex Salmond, David Cameron, Ed Miliband, Jim Murphy, Alistair Darling, Nick Clegg. All consigned to history.

Mr Salmond was replaced by Ms Sturgeon, taking himself off to Westminster and a promising career as a radio host.

David Cameron eventually made way for Theresa May, courtesy of that other referendum. Mrs May has pledged to "listen to options" about Scotland's future, but has one or two other things on her plate to worry about.

Ed Miliband was replaced by Jeremy Corbyn, who continues to fight for his position at the head of a UK Labour party which seems hopelessly divided and doomed to perpetual infighting.

Jim Murphy was succeeded by Kezia Dugdale, with Scottish Labour seeming to change bosses more often than a struggling Premiership football team.

Better Together boss Alistair Darling decided against contesting his Edinburgh seat in 2015, which was subsequently swept away in the SNP tide. Nick Clegg walked away from the Lib Dem leadership after guiding them from 57 seats to just eight at that same election.

One may have noticed, of course, that these are largely players from the unionist team; another field where victory in 2014 was no guarantee of future success.

Meanwhile many stars of the defeated Yes campaign prospered, beyond the obvious example of Ms Sturgeon; think of Mhairi Black taking Douglas Alexander's Westminster seat, or Jeane Freeman winning a place at Holyrood and immediately becoming a minister.

Brexit

Several pro-EU rallies were held at Holyrood in the aftermath of the Brexit vote

It's probable that without the impact of the EU referendum, this anniversary would have passed off as a far more low-key affair. But the Brexit vote made a mockery of many assumptions, and has given fresh life to the independence movement.

The majority of Scots who turned out voted to Remain, while UK-wide it was Leave who were triumphant.

Potentially crucially, the SNP's 2016 manifesto had cited this exact scenario as a "significant and material change" which would entitle them to pursue indyref2 - although of course the SNP did fail to win a majority with that manifesto.

Underneath the headline numbers were some significant sub-plots. Turnout slid to 67.2%, meaning Remain's healthy 62% majority was won with only 1.6m votes - very close to the minority who voted Yes in 2014.

And there were plenty of SNP supporters among the million Leave voters north of the border - a not inconsiderable tally given that only UKIP, which won a measly 2% of the Holyrood vote seven weeks earlier, had formally backed Brexit.

Jean-Claude Juncker was among the EU officials and MEPs to meet Ms Sturgeon on a visit to Brussels after the Brexit vote

In the immediate aftermath of June's vote, Ms Sturgeon said a second independence referendum was "highly likely".

She pointed out that one of the promises of the Better Together side in 2014 had been that an independent Scotland might not be allowed into the EU, and that voting No would protect Scotland's place in the club.

The first minister jetted off around Europe to meet various continental statesmen, and would have been very pleased to see Guy Verhofstadt, a former Belgian PM who had said it would be "wrong" for Scotland to be "taken out" of the EU, given a key negotiating role.

The Brexit vote creates uncertainty about the UK's future, which is both good and bad for Ms Sturgeon.

On the one hand she can use the differing results north and south of the border to paint a picture of two countries heading in different directions. But equally, nobody knows yet what Brexit will look like - so it's hard for Yessers to say what in independent Scotland would be leaving, or indeed going to.

The economy

Tens of thousands of jobs have been lost in Aberdeen since the oil price slump began

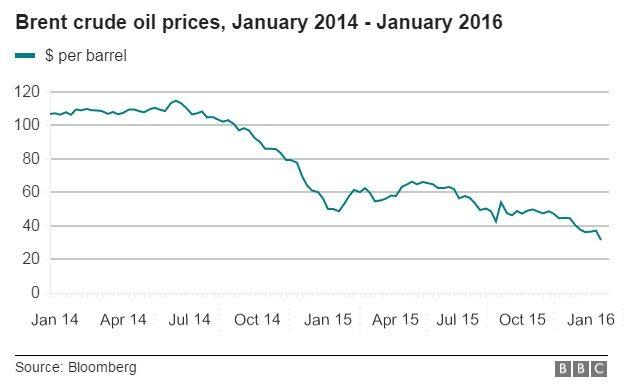

In September 2014, if so inclined you could buy a barrel of crude oil for about $95. Today, that same barrel would cost you closer to $45.

The economic foundation of Alex Salmond's White Paper on independence was a sunny optimism regarding the price of oil. That optimism has now dissipated utterly.

Plunging oil prices, felt most sharply in Aberdeen where tens of thousands of jobs have simply disappeared, have seen Scotland's share of North Sea revenues fall 97% in the past year.

The latest set of GERS figures illustrated a near £15bn gap in Scotland's finances, at 9.5% of GDP more than double that of the UK as a whole. Grim reading for Ms Sturgeon and her government, although she has insisted that the "foundations of the Scottish economy remain strong".

There have been further tremors in the wake of the EU vote, with the pound palpitating - and Ms Sturgeon has pointed out that Brexit hasn't even happened yet, warning of a "lost decade" of economic turmoil.

Talking of the pound, currency was another indyref sticking point - and another one which remains unresolved for any future campaign.

If a future indyref2 were based around the idea of EU membership, the Euro will have to at least come into the conversation.

In 2014 then-chancellor George Osborne threatened to cut an independent Scotland off from the pound, and a series of figures including Mr Salmond and Nobel-prize winning economist Joseph Stiglitz have accepted that the argument did not go well for the Yes side.

Electoral dominance aside, the SNP have a lot of work to do to rebuild an economic case for independence.

The electorate

Voter fatigue may be setting in after a whirlwind of elections and referendums in Scotland

Despite everything listed above, it seems that one critical thing has not changed that much in Scotland over the past two years - the feeling towards independence.

The Brexit vote prompted a flurry of new polls on the subject, somewhat ironic given the failure of pollsters to forecast the outcome of the EU vote.

The Yes vote saw an immediate bounce - but not quite of the margin Ms Sturgeon would have wanted or perhaps expected. And since then the indications are that support for independence has fallen back to roughly the level it was at in September 2014, with Brexit hardly making a dent.

Polling guru John Curtice crunched the numbers and found "little or no evidence of a swing in favour of independence".

Additionally, there is evidence that voter fatigue is starting to set in; from that record high in 2014, turnout has been slipping at each successive election.

So looking back, it appears that Nicola Sturgeon is quite right to say that we live in rather markedly different times compared with September 2014.

Her party has done very well over that time, but she hasn't had it all her own way - and she still has quite a few questions to answer before she will consider taking Scotland back to the polls for a rerun of 2014.

- Published12 September 2016

- Published7 September 2016

- Published2 September 2016