What to look out for in the Scottish Budget

- Published

Mr Swinney has some tough decisions to make as the country grapples with a cost of living crisis and soaring inflation

It was quite the autumn for budgets. Who could forget Kwasi Kwarteng's spectacular tax-slashing experiment without figuring out what it would cost and how it would be paid for?

His successor threw that into reverse. Jeremy Hunt presented a package of tax increases, some measures to help the economy through recession, and then a fierce spending squeeze in the years to follow.

As the new Chancellor, he was not focussed so much on next financial year, starting in April 2023. His was a five-year outlook. His budget for 2023-24 is to be set out early next year.

In September and then November, John Swinney, as stand-in Holyrood finance secretary during Kate Forbes' maternity leave, set out emergency budget revisions for the current year, and he may not yet be finished with that.

There have been higher public sector pay bills than expected when the budget was set last year, and underspent programmes took a hit as a consequence.

Mr Swinney said inflation cost the current year's budget £1.7bn. Experts at the Fraser of Allander Institute point out the minister's calculation uses consumer price inflation, but the government's price inflation is not as high. They reckon the gap is closer to £1bn. It's still a lot.

This week, with the economic dashboard registering chilly wintry territory, Mr Swinney sets out his draft budget for 2023-24, for consideration by MSPs over the next two months.

Moving parts

Jeremy Hunt outlined plans for tax rises and spending squeezes in his recent Autumn statement

Mr Swinney has said there has never been more uncertainty around budget planning, though some of that was removed by Jeremy Hunt's autumn statement on 17 November.

The Scottish administration now has a better idea of what's likely to be in next year's Westminster budget, and can plan on the larger part of a £1.5bn uplift in budget over the next two years. That is reckoned to mean that the budget rises roughly in line with the rising cost of government, meaning this is not set to be the toughest of budgets over this decade.

What is less certain is the trajectory of prices, with inflation high, a cost of living crisis eating deep into a wide spectrum of household and business spending, and the Bank of England base interest rate likely to continue its rise less than three hours before the Holyrood budget is presented.

Growth is uncertain, though there's a strong expectation of recession during this winter and well into next year. A downturn sets back revenue from tax, and puts more pressure on governments to respond. Most governments do that by borrowing, but Holyrood's powers to borrow are limited.

The inflation and growth rates in the economy and in revenue with which Mr Swinney has to juggle are set for him by the Scottish Fiscal Commission (SFC). An independent body, just like the Office for Budget Responsibility, it gets to see options for his budget over the preceding two months.

And as the deputy first minister ends his statement on Thursday, the SFC will publish its findings on growth or contraction in the Scottish economy, on the path of inflation and unemployment, on tax revenue, on the likely cost of welfare benefits controlled at Holyrood, and on economic consequences of the budget.

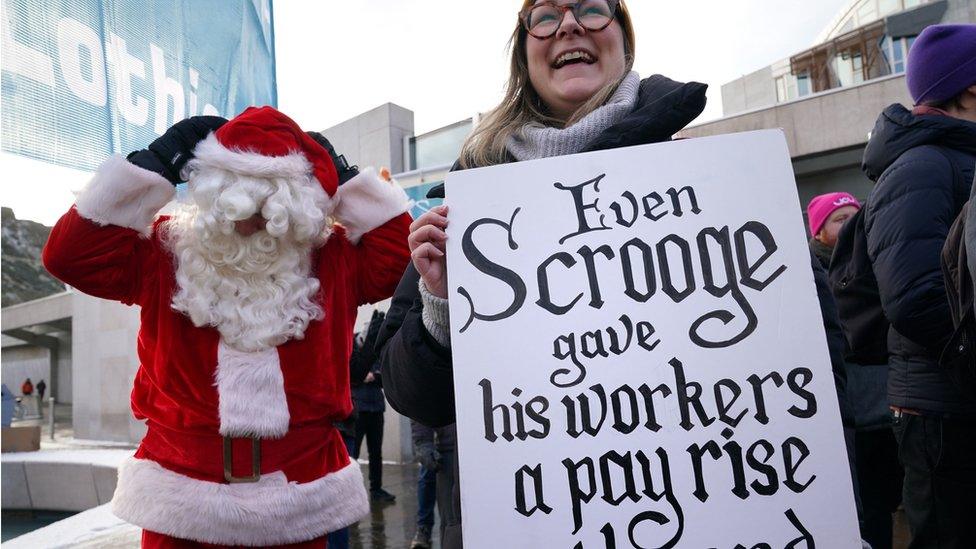

Pay claims

Scottish teachers have been out on strike

Among the most difficult and important calls to be made in this budget will be the public sector pay policy.

The Office for National Statistics said on Tuesday that the gap between public and private sector pay across the UK is very wide - 2.7% to 6.9% in the year to October. That's in cash terms. From that, subtract 9% consumer price inflation in the preceding 12 months, and you can see the scale of falling real incomes and spending power.

Government services have many more trade union members than private firms. Those factors help explain why there are so many strikes and threats of strikes in pursuit of pay claims that seek to match price inflation but which are mostly falling far short.

Within the pay policy in this week's budget, Mr Swinney could offer pay rises if there is a cut in headcount. There's already an effective recruitment freeze across much of the public sector, and that cut in the workforce was set as a target last May.

The finance secretary could also tie pay to reform of contractual conditions, though the SNP has avoided doing much of that in the past, and looks unlikely to provoke unions while they are so active.

Most of budget day, however, is about how much money is available, how it's raised, and how it will be spent.

Income

Much of the budget for Holyrood comes from the block grant allocated by the Treasury. The size of it flows from the 44-year old Barnett Formula, but with big adjustments.

Where it allocates more to health in England, a fixed share of that comes to Scotland, as well as shares to Wales and Northern Ireland. The same is true of English schooling, which is getting an uplift.

But if there are cuts in English spending on items that are devolved, that will also be reflected in the grants to devolved administrations.

The Treasury deducts the amount it would have raised if it were still collecting income tax in Scotland.

It adds the amount it would be paying out in Scotland on those welfare benefits that have been devolved to Holyrood. But if Holyrood wants to pay more in benefits, it has to find the funds elsewhere.

What, then, can John Swinney do to make up the other third or so of his budget. The biggest share of that is in Scottish income tax. That has diverged from Westminster income tax rates and thresholds, but with the exception of the level at which people start to pay higher rate tax at 41%, there isn't much divergence.

There will be a lot of focus on what Mr Swinney chooses to do with income tax rates in Scotland

At Westminster, Jeremy Hunt is freezing thresholds for tax rates while holding the rates steady. That is a substantial stealth tax on earners as their pay goes through these thresholds, and with inflation, many people are doing just that.

Not to freeze thresholds in Scotland would be a tax giveaway, relative to England at least. It would be difficult financially not to follow the Chancellor in doing that, and politically it would be odd not to take that more progressive approach.

Mr Hunt also reduced the threshold at which additional rate is paid at 45p for each extra pound earned. That is coming down from £150,000, which is the level it has been at for more than a decade, to just over £125,000. Again, it would be odd for the SNP, which levies that tax at a rate of 46p in the pound, not to do something similar.

For higher earners, Scotland already has a higher tax rate than the rest of the UK, by 1p in the pound. Mr Swinney could choose to raise that further. But higher tax, while household budgets are being squeezed by inflation, could harm efforts to return the economy to growth.

Other important decisions include council tax. Will Mr Swinney constrain the ability of councils to raise their tax bills, as he did for several years as finance secretary? While Green MSPs are pressing for major reform of council tax, there's a lot more talking before that happens.

Will the cabinet secretary respond to lobbying from Scottish business, not to impose higher business rates bills on them, and to close a gap with the rates paid in England?

And will he at least acknowledge pressure from the left, including the STUC trade union body, to fund public sector pay with a sharp increase in taxes on those earning over about £40,000, and then to tax wealth?

How much the Scottish government wishes to alter tax, and possibly raise more, is closely linked to how much it wants or needs to spend.

Spending

Last year's Budget was dominated by the costs of Covid. That continues to cast a long shadow. Many public services are struggling with numerous backlogs, from health procedures to court cases. Staff vacancies are high as retention of workers proves difficult.

Mr Swinney has no shortage of demands on his money. But the Fraser of Allander Institute economists say much of that is committed to the priorities already set out. The NHS gets a protected status, though it may not get either enough, or the same level of increase that has been seen in Whitehall. Scottish ministers may judge, for instance, that the health service's problems are not only financial but need other solutions.

Social care is a priority for this five-year term of office, with the creation of the National Care Service. The cost of it ranges between unclear and astronomic. But just setting up is likely to cost a lot, while raising expectations of what it will deliver. One of the high costs is its intended role of ensuring higher pay for care workers.

Welfare benefits are the newish element in Holyrood's budget, gradually being devolved. The biggest tranche of money being shifted from the Department of Work and Pensions came last year. With it came expectations that Scotland would have a more generous welfare system.

That generosity is proving to be expensive, and spending watchdogs have warned of other budgets being squeezed in order to meet the commitments to new benefits, such as the Scottish Child Payment. There is also concern in Scottish government at the high cost of the commitment to support Ukrainian refugees.

Indications from the five-year Holyrood spending outlook, set out last May, are of some very tight budgets for other departments, local government grants down 7% in real terms between this year and 2026. Enterprise agencies are down 16% in that period. Universities, colleges and student grant, plus police, prisons, fire and rescue and legal aid were told to plan for real terms reductions of 8% over four years.

Things have changed since then, including higher inflation and likely recession, and some of that plan has already been altered.

Political cost of living

The Budget is not just about finance and economics. It's also about politics.

When an administration lacks a majority of MSP votes, the draft version is subject to negotiation with opposition parties to ensure the Finance Bill can pass. That is not the case while Green MSPs share power with the SNP. The negotiations have already taken place behind the scenes. A majority is assured.

While John Swinney therefore does not have to find more money over winter to ease that process, that does not mean he won't find some, to reflect concerns about the cost of living.

Responding to that public and business anxiety about prices is going to be one of the main tasks of this budget. But Holyrood lacks Westminster's flexibility with borrowing, allowing the Treasury to help with energy and other bills on a very large scale.

The Deputy First Minister won't miss the opportunity to complain about that state of constitutional affairs. But as things stand, there is less he can do.