Frongoch: The University of Revolution

- Published

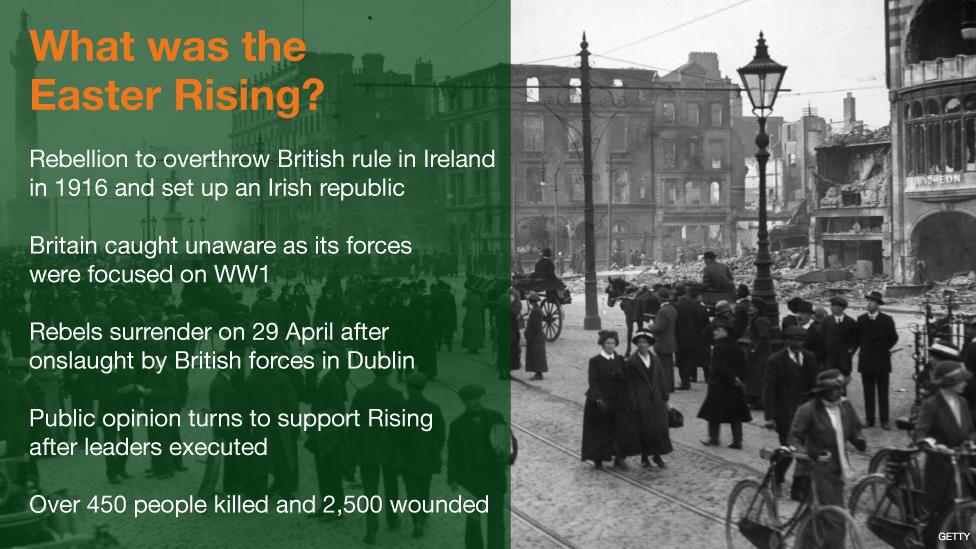

In ruins - Dublin's General Post Office in 1916

A ceremony to commemorate those killed in Ireland's Easter Rising a century ago is being held in a Welsh village that became pivotal in shaping the Republic's future.

It comes as wreaths are laid across Ireland on Easter Monday to mark the loss of more than 450 lives in the week of battles between British troops and rebel fighters in Dublin in 1916.

In the aftermath, the British authorities rounded up anyone suspected of taking part in the insurrection.

For 1,800 of those arrested it meant imprisonment without trial in the rolling hills of Snowdonia.

They were defeated, imprisoned and their leaders executed. It should have been the end of Ireland's independence rebellion.

Yet just five years after the failed Easter Rising in 1916, some of those very same rebels had secured a deal establishing the Irish Free State.

There are plenty of reasons why - personalities, politics and places.

And one place in particular played its role - but it was not in Ireland.

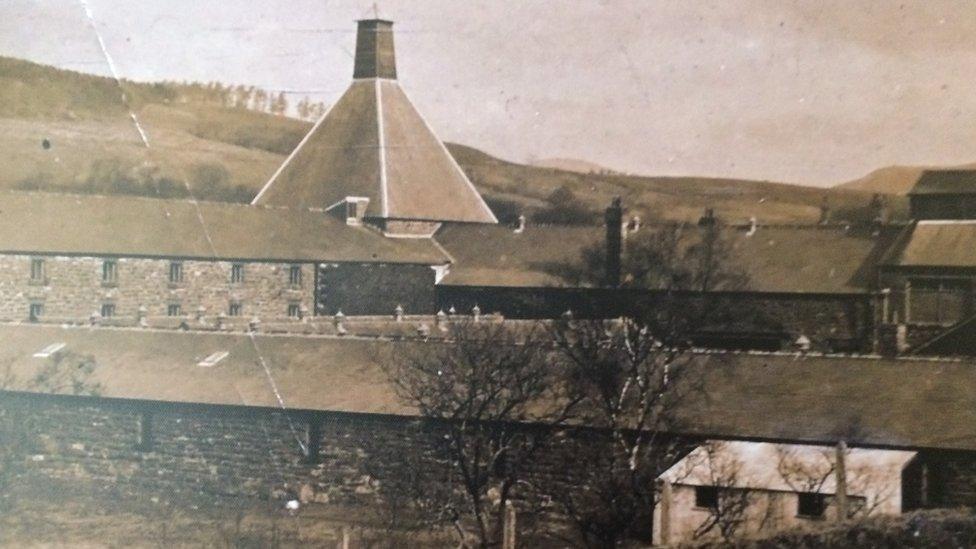

It was a disused Welsh whiskey distillery on the eastern edge of what is now the Snowdonia National Park - Frongoch.

To those who have been marking the centenary of 1916 on the Easter weekend, it is Ollscoil na Réabhlóide- the University of Revolution.

Its graduates included Michael Collins - a bit-part player in the events that unfolded at the General Post Office in Dublin, where the Irish tricolour was unfurled on Easter Monday as the armed uprising began.

But Frongoch changed Collins. From the cauldron of incarceration he emerged as a leader, a strategist, a guerrilla fighter, a financier and a manipulator.

Michael Collins - a photograph taken on his release from Frongoch. His hand rests on his knee, covering a hole in his trousers

"He was relatively insignificant when he went to Frongoch," argued Prof Michael Laffan, of University College Dublin, in a special BBC Radio Wales documentary to mark the Easter Rising.

"But there in the prisoner of war camp, he showed his organising abilities. He revealed his skill in manipulating, in charming, in dominating people. He was a bully - he was highly efficient.

"He emerged as a leader, and when he went back along with all the others who had been interned, to Ireland at Christmas 1916, he went back as a man with a reputation.

"He was the one who emerged from Frongoch and became, undoubtedly, the most important figure in the Irish Revolution."

Along with the founder of Sinn Féin Arthur Griffith, Collins became one of the men who would lead negotiations in London in 1921 to establish the Irish Free State.

In total, at least 30 men held at the camp went on to become MPs in the new Irish parliament in Dublin.

Camp life

The first of the 1,800 men to be held at Frongoch began arriving at the camp in June 1916, taken by train from prisons across England.

It had already been used to house German PoWs captured in the ongoing World War One conflict.

Collins himself noted in letters home that the camp was "situated most picturesquely on rising ground amid pretty Welsh hills".

But he added: "Up to the present it hasn't presented any good points to me, for it rained all the time... so that all the ground around and between the huts is a mass of slippery, shifting mud."

The camp was divided into two parts, with men crowded into cold wooden huts in the north section, while in south camp prisoners were forced to endure a hothouse environment in the old distillery buildings.

The rear of the distillery buildings in south camp at Frongoch

Along with the rain and mud, the inmates had other problems to occupy them - food and rats.

The whole camp was infested with rodents, earning it the nickname Francach - a pun on the Irish word for rat.

The daily complaints about the camp diet ended with the issue being raised in the House of Commons on several occasions.

One incident included the camp doctor condemning a delivery of meat as unfit for human consumption, after the prisoners were told to wash it in vinegar to remove the stench of rotting flesh.

"Reference has been made to the treatment of political prisoners at Frongoch, and denials were made by ministers as to their treatment as far as food and other matters are concerned," stated the Tullamore MP Edward Graham in October 1916.

"I have no faith whatever in replies given by right honourable gentlemen on the Treasury Bench as regards these unfortunate prisoners."

Over the summer months, the numbers of those interned dwindled rapidly as many were allowed to return to Ireland, satisfying British officials that they had little to do with the uprising.

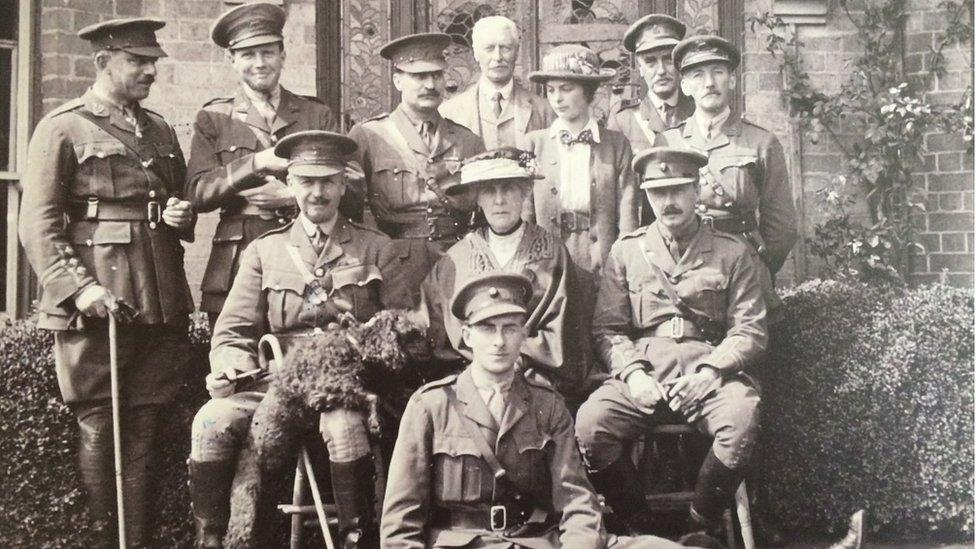

Camp officials at Frongoch - the house is one of the few buildings that remains intact today.

Fighting on

For those that remained - some 600 men - camp life was organised around sporting events, such as Gaelic football on a field that is still known today as Croke Park in the village, and of course, the burning question of Ireland's future.

It led to lessons in the tactics of guerrilla warfare and intelligence networks, focused around the secret Irish Republican Brotherhood society, over which Collins would later preside.

"They learned different ways of fighting against the British, because they found out that holding buildings during the Rising in Dublin just didn't work," explained Alwyn Jones, who lives in a house on the foundations of the old whiskey distillery at Frongoch.

"We are talking definitely about guerrilla warfare - hit and run mostly."

The retired farmer is one of those who helps organise commemorations in the village, including a planned parade in June to mark 100 years since the first prisoners arrived in Wales.

"Some of those at Frongoch were hardcore revolutionaries and it made them even harder really," he added.

"It gave them resolve to fight on."

Frongoch today - farming fields and homes

As the months dragged on in the camp, tempers frayed over attempts to discover if any of the inmates were eligible for conscription into the British Army for the war in France and over demands to carry out work - including clearing soldiers' rooms.

There was a three-day hunger strike and incidents of prisoners refusing to dress or answer roll call.

The accounts of camp life were finally made public in newspaper articles, including the then influential Manchester Guardian, and on 21 December 1916 an amnesty for those interned was announced.

Huge crowds gathered in Dublin to witness the return of the Frongoch men at Christmas - proclaimed as heroes of Ireland.

The Irish nationalist MP and lawyer Timothy Healy summed up his feelings about Frongoch in a stinging attack on the then Home Secretary Herbert Samuel in the early days of the camp regime.

"He has started a Sinn Féin academy, a Sinn Féin university at Frongoch in Wales, where he has brought together some 2,000 men, guilty and innocent.

"Instead of these men being left at home in their little farms and cottages, scattered and dispersed as they were from one end of Ireland to another, he has congregated them together - Ulstermen, Munstermen, Connaughtmen, Leinstermen, men who have never met - and has enabled them to exchange ideas.

"I regard the right honourable gentleman the Home Secretary as the father of the Sinn Féin movement."

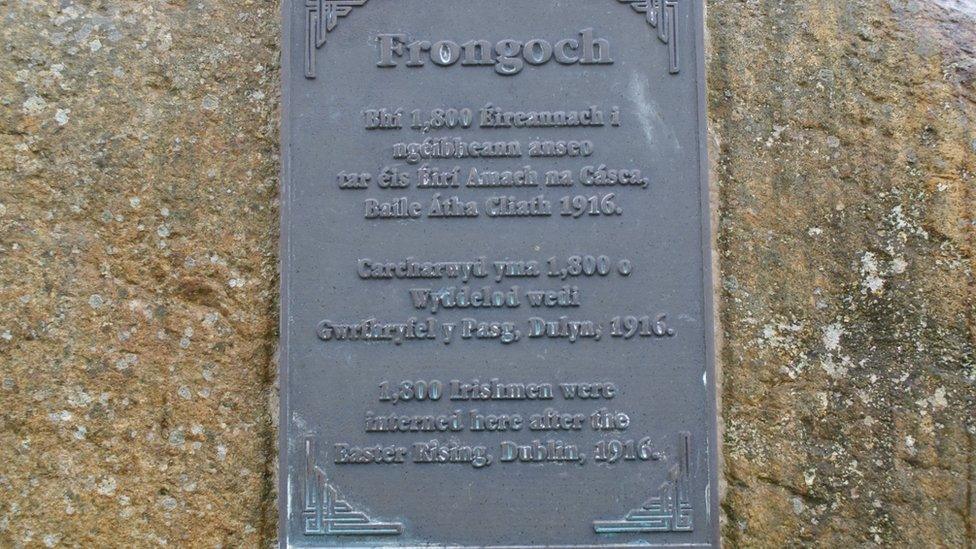

A plaque in the village to mark the camp - inscribed in Irish, Welsh and English

In 1918, Sinn Féin won a landslide victory in the General Election in Ireland and in January 1919 formed a breakaway government.

That in turn sparked the Irish War of Independence, the guerrilla conflict that eventually led to the treaty establishing the Irish Free State, and later what is today's independent Republic of Ireland.

- Published25 March 2016

- Published25 March 2016

- Published24 March 2016