Does Swansea deserve to be UK City of Culture 2021?

- Published

Swansea's Millennium Bridge is a landmark feature in the city

It's the birthplace of poet Dylan Thomas and Catherine Zeta-Jones; it grew wealthy in the 19th Century as "the copper capital of the world"; it's next door to the Gower Peninsula, Britain's first area of outstanding natural beauty.

And now it's one of five places bidding to be the UK's City of Culture in 2021, after Derry/Londonderry in 2013 and this year's holder of the title, Hull.

Like its rivals — Paisley, Sunderland, Stoke-on-Trent and Coventry — Swansea's the sort of place where the locals are apt to look baffled when you talk about culture, and disbelieving when you tell their home town wants to be city of culture (a message that's failed to reach many of its inhabitants, to judge by the random sample we stopped outside Swansea's enormous market).

Does Paisley deserve to be City of Culture?

Is Sunderland about to have an artistic renaissance?

Could Stoke be City of Culture?

Is Coventry about to have a moment of glory?

But it turns out that, beneath its sometimes drab exterior, Swansea has plenty of culture.

Rob Stewart, leader of Swansea council, calls the place "the cultural capital of Wales", a claim they might dispute in Cardiff, just up the coast.

But when he rattles off a list of its qualifications you take his point. Yes there's Dylan Thomas, and the magnificent Swansea Bay, stretching from the old docks at one end to the lighthouse and lifeboat station at The Mumbles at the other.

But there's also the Glynn Vivian art gallery, recently refurbished and extended and a regional partner of the Tate. There's the National Waterfront Museum, dedicated to the city's industrial heritage. And soon there'll be a waterfront "digital arena", with a 3,500 capacity for shows, concerts and exhibitions equipped with all the latest technology, on which construction is due to start early next year.

This is the second time Swansea has bid to be city of culture. Last time it lost out to Hull.

Unlike last time, Mr Stewart says, on this occasion the city council is driving the bid and the Welsh Government is supporting it. Even so Swansea was a late entrant to this year's race - it only declared at the start of this year, whereas its rivals have been up and running, drumming up local support, since 2015.

The rules say heritage must be a key part of any bid — and there's £3m on offer from the Heritage Lottery Fund to the winning city. Swansea's problem, shared with some of the other bidders, is that so much of its heritage has disappeared.

Mr Stewart and I talked in Swansea Museum's warehouse store, surrounded by old sailing boats, vintage vehicles and a typical museum storehouse collage of, well, junk. It's next to a park-and-ride and just across the road from Swansea City FC's Liberty Stadium (Swansea has the only Premier League team in Wales, as I was repeatedly reminded).

This whole area, down by the River Tawe, was once the heart of the local copper industry, one long line of foundries, massive slag heaps and the most appalling pollution.

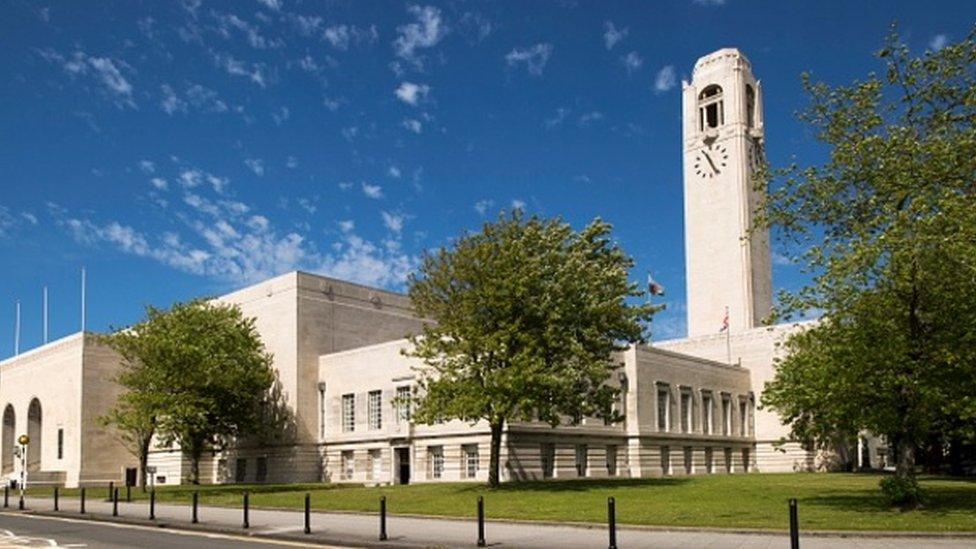

Swansea's Guildhall has been used as a backdrop in several films including Their Finest

Now all that remains are the ruins of the Hafod Morfa Copperworks next door to the museum store. The works finally closed in 1980. There are plans to convert part of the site into a visitor centre for Wales' only whisky distillery. Meanwhile schoolchildren are given tours of the ruins, to learn about an often grim industrial past even their parents are too young to remember.

Using heritage, tourism and culture as a tool of regeneration is nothing new in Swansea. Not so long ago many of the properties in the dilapidated High Street were derelict. Now many have been refurbished, redeveloped or brought back into use by a housing association, Coastal Housing, with a policy of letting space cheaply to arts organisations.

Half way down is The Hyst, a bar and music venue run by musician and broadcaster Mal Pope — he presents the early morning show on BBC Radio Wales from a Swansea studio.

He sees the cultural and creative industries as key to Swansea's continuing recovery. "I've been a musician since I was 13," he told me. "My parents were always worried. They wanted me to be a teacher so I had something to fall back on. But teachers are leaving the profession. If you worked in steel it wasn't a job for life. Creating... that's a job for life. It's up to you to create your own work."

Swansea people already think that way, he says - becoming city of culture would give the process a boost and give the city a new found confidence.

Across the road from The Hyst is Volcano, a community theatre organisation housed in a former department store. Paul Davies, its director, is equally keen on the city of culture bid, though wary of what it might become.

There are £500m plans to regenerate Swansea city centre

"It can only work if the culture isn't coming from the south east to us," he says. It can't be what he calls "just another road programme" imposed from elsewhere. "It needs to be culture from the bottom up. It needs to be an organic, community-led cultural vision and practice, otherwise it's not going to feed into the wider debate about real economic change."

And upstairs and round the back of Volcano is the remarkable Elysium Studios, with three sites in the city centre, which between them provide space for almost a hundred artists.

To walk round Elysium, with its artists each toiling away and showcasing their work in open booths, is to see creativity made manifest: painters, sculptors, conceptual artists, print-makers, illustrators, photographers.

Stephen Rew at work in Elysium Studios

Stephen Rew is busily creating images of sea and surf by pouring coloured resins onto hardboard and attacking them with a blowtorch.

Kate Bell spent 30 years as an art teacher before turning to painting full time.

Kathryn Trussler makes work out of discarded polystyrene which she describes as belonging in "a post-apocalyptic zen garden". A graduate of Swansea College of Art, now part of the University of Wales Trinity St David, she had to head back to her parents in Hereford until a space came free at Elysium, enabling her to return to Swansea.

Jonathan Powell, a working painter himself who also runs Elysium, says in the past many young artists ended up leaving the city. Now there's a reason for them to stay, somewhere that offers cheap studio space and a community of like-minded folk with whom to gossip, bounce ideas off or collaborate.

My suspicion is that Swansea, late as it was in entering the race, is still playing catch up. But when TV producer and writer Phil Redmond and his colleagues on the panel deciding who will win this competition visit the city on Monday, it's clear they'll find plenty to chew on.

They'll make their final decision in December. It'll be announced in Hull at the close of the year.

- Published28 September 2017

- Published15 July 2017

- Published14 July 2017