How World War One heralded social reforms

- Published

David Lloyd George speaking to a crowd at Lampeter, Ceredigion, in 1919

Even before the guns fell silent on the Western Front, the long-term social consequences of World War One were being felt back home.

Women had a stronger voice, education, health and housing appeared on the government's radar, and the old politics were swept away.

Historical debate still continues as to whether these changes would have occurred even without the war.

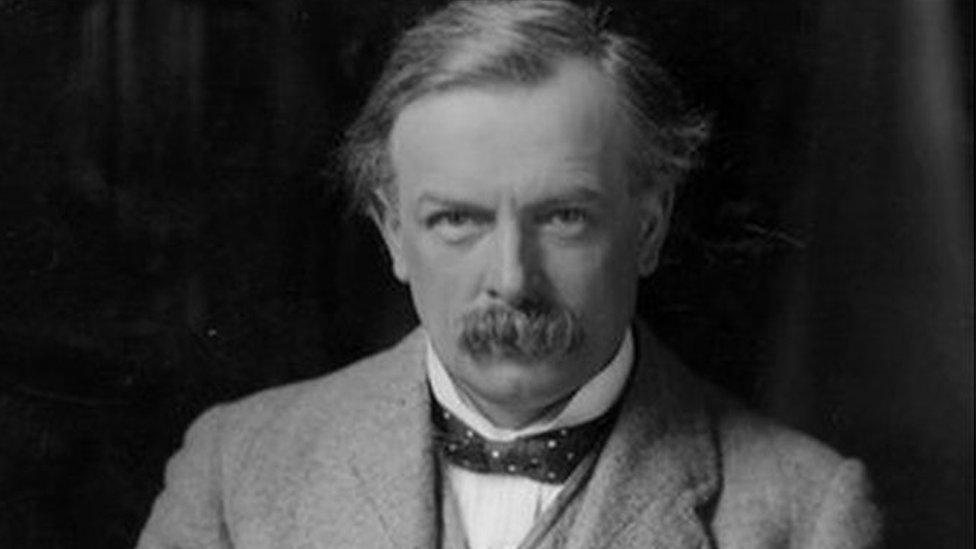

Dr Gerry Oram, director of Swansea University's war and society programme, believes Welsh Prime Minister David Lloyd George was probably the driving force behind these changes.

"Right from the very start of the war and certainly from 1915, Lloyd George, as munitions minister, was adopting a more interventionist form of government, with state control of labour, weapons production, Dora (Defence of The Realm Act) and all the ancillary services which made this total war possible," he said.

"It was a necessary departure from the laissez-faire 'old liberal' politics, but it continued into the post-war era.

"I don't think you can say it can all be entirely attributed to the war.

"Even before 1914 there had been some attempts at education and pension reform, but it took a combination of an event as massive as World War One, and someone with the radical north Wales nonconformist background of Lloyd George, to shake up conventional political wisdom."

The most obvious sign of social change was the altered status of women.

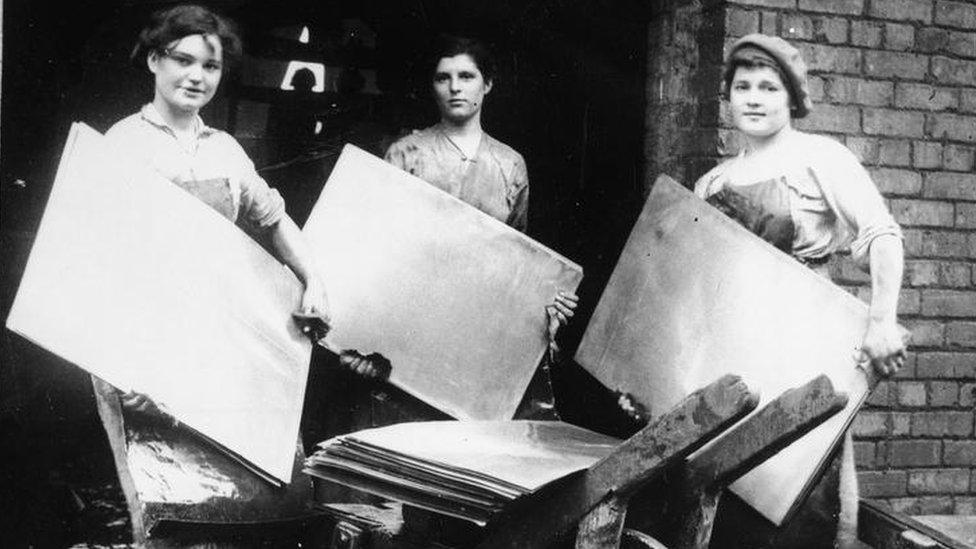

Group of female workers employed at a brickworks in south Wales during WW1

The Representation of the People Act 1918 granted the vote to all men over the age of 21, and 8.5m women over 30 who were householders or who owned property.

This was further bolstered by The Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act of 1919, which made it illegal to exclude women from jobs because of their gender.

"There was little point in pretending any more, women had proved they could take on the roles vacated by men, and they'd played an enormous part in winning the war," said Dr Oram.

He said in Wales in particular there was something of a disconnect between the theory and practice of the new legislation.

"In theory women had legal protection, but given the post-war collapse of heavy industry in Wales, there were even fewer jobs to go around here than elsewhere," he said.

"Add to that the amount of seriously wounded men coming home who required constant care, and in many instances women's lots were actually considerably worse after 1918.

"The Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act was at odds with other legislation which promised servicemen their pre-war jobs back when they returned, and there remained a marriage bar in some areas of employment, including teaching.

"In fact, in Wales women had comprised 27% of the labour force in 1911, but that actually fell to 21% by 1931."

Female sheet metal workers transporting tin plates from the pickling room at Beaufort Tin Plate Works in Morriston during WW1

Other areas to receive a radical post-war rethink were education, health and housing.

The Education Act 1918, external enforced a compulsory school-leaving age of 14 for the first time, special educational needs were recognised, and school meals and regular health-checks were introduced.

The Ministry of Health Act 1919, external made citizens' health a government responsibility by establishing the first ever minister for health.

The wartime National Health Insurance Scheme was gradually expanded so that by the post war period it covered all workers, and by the mid 1920s similar insurance schemes for unemployment and old age had also been introduced.

Meanwhile, the Housing and Town Planning Act of 1919, external was meant to provide subsidies for local authorities to build 500,000 new houses within three years.

But were these truly altruistic and progressive policies?

Dr Oram said: "I don't think it's particularly helpful to view the debate in terms of, at one extreme, a new era of progressive politics, or at the other, a cynical attempt to ensure Britain was better placed to fight another total war.

"Certainly it's true to say that World War One had shown up the lamentable health and education of some conscripts, and the government had to act to remedy that.

"Equally, it's probably true that without wholesale government intervention, private industry would not have been able or willing to mobilise itself on a total war footing.

"However, the government was responding to a national sense that, after four years of war, the people ought to have something to show for it.

"The threat of Bolshevism following the Russian revolution, and the suffragette movement at home both demanded a fairer social deal if domestic conflict was to be avoided.

"I believe you can see the reforms as typically Lloyd George: combining idealism and pragmatism."

David Lloyd George, born in Manchester on 17 January 1863, spent most of his childhood in Llanystumdwy in Gwynedd

Nowhere was that combination of idealism and pragmatism better demonstrated than in Lloyd George's unprecedented hike in death-duty.

In 1917 he raised the rate for all mobilised men to 12%, the estates of Cambridge students were taxed 18%, and the families of those from Oxford University and members of the peerage faced a bill of 19%.

Lloyd George publically spun it as a progressive redistribution of wealth, though many suspected him of using the disproportionate death rate of wealthy officers on the Western Front as a cash cow to boost a sorely stretched exchequer.

When addressing the causes of the post-war decline of the nobility in his book Deluge, Arthur Marwick succinctly put it down to "duty, death, death-duty". So what was the enduring legacy of the post-war reforms?

Dr Oram said that, as in the case of female suffrage, not all of the benefits were immediately apparent.

"In some ways the reality of swingeing post-war austerity meant that many of the projects were pared back.

"Lloyd George had promised 'Homes Fit for Heroes', though in reality less than 50% of the planned half a million houses were ever built.

"Perhaps more than the actual physical results, the true legacy of the post-war reforms was to change political thinking, and set out a blueprint for future governments.

"The expansion of the health insurance scheme is arguably laying the groundwork for the NHS, whilst pension and unemployment provision form the foundations on which the Beveridge reforms were built a quarter of a century later."

- Published7 November 2018

- Published6 November 2018