Contaminated blood inquiry: Doctor withheld HIV diagnosis

- Published

'I feel guilt that we allowed it to happen'

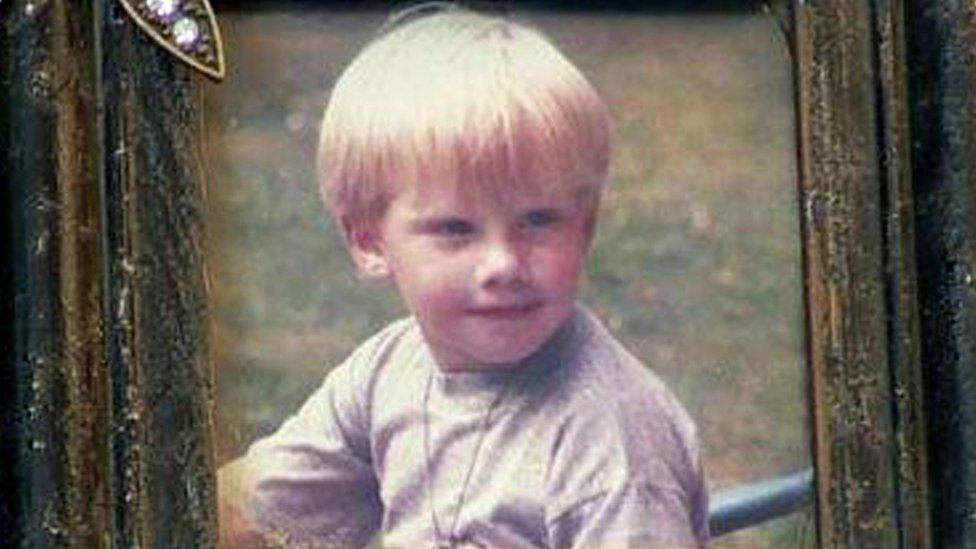

Paul Summers was five when he was diagnosed with the blood disorder haemophilia in 1969. His parents Pat and Tony were shocked, but also relieved.

They had spent their son's early years ferrying him from their home in Llantwit Major to Bridgend hospital with unexplained bruises and bleeding problems.

A knock or cut could see the active little boy in hospital for weeks.

When a revolutionary new treatment called Factor VIII was proposed by doctors in the late 1970s, a teenage Paul was thrilled he could inject himself at home, freed of regular trips to the haemophiliac unit at Cardiff's Royal Infirmary for blood transfusions.

Tony drew the line at contact sports such as rugby, but Paul "could lead a full life, go on school trips, play sport and go on skiing holidays".

Looking back, they now believe doctors were screening their school-age son for HIV without their knowledge - and he was eventually infected at the age of 18.

They want answers about their son's treatment and have taken part in the Cardiff leg of inquiry into the contaminated blood scandal.

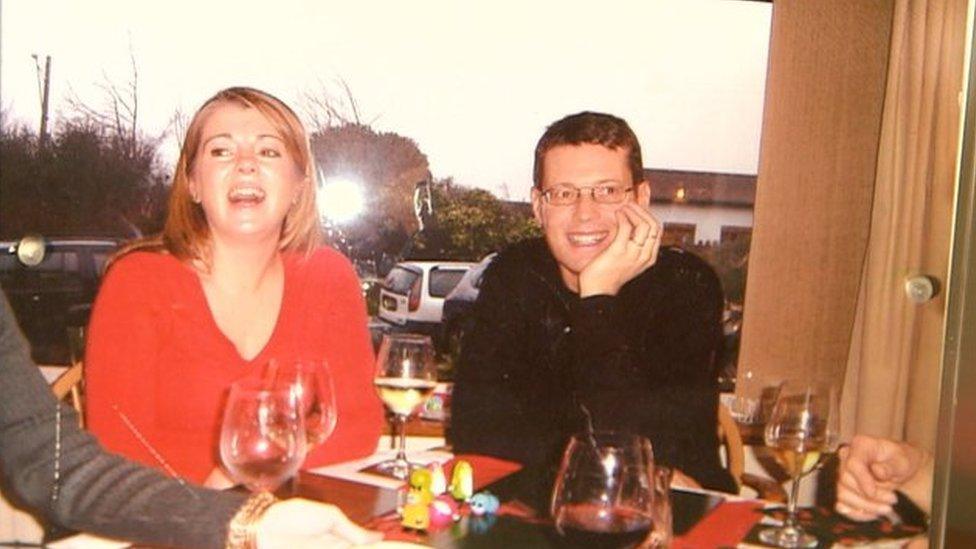

Paul with his sister Bethan - the family were afraid to reveal his HIV diagnosis to the wider world

About 40 years ago, Paul and his younger sister Bethan were busy growing up, but Tony and Pat began to hear about stories in American newspapers suggesting there were problems with Factor VIII, which was derived from thousands of pooled blood donations, including, it eventually transpired, prisoners and drug addicts.

Tony recalled: "I kept asking at the hospital. They said there's no problem, everything is fine. We continued believing it.

"Why should I doubt them? These were professional people caring for my son."

Retired teacher Pat and former businessman Tony look back with pride at their son's drive, stoicism and "wicked sense of humour" in the face of his haemophilia.

After initially studying in Bristol, Paul started an architecture degree in Plymouth in 1986 and his medical notes were transferred to Derriford Hospital.

The doctors there called him in for a series of blood tests to verify what was written in his Cardiff records - it had been confirmed he was HIV positive at least a year earlier. He had not been told.

Paul graduated from university in Plymouth, where doctors told him he was HIV positive

Tony was with Paul when doctors in Plymouth broke the news. They quietly told Tony his son, then 22, was unlikely to reach his 50th birthday.

"He was extraordinary how he took it. We stood outside the hospital saying 'what do we do now?' and his reaction was 'well, I could do with a couple of new pairs of jeans', and then he wouldn't mind taking me for a steak and we'd talk about it," said Tony.

It was 1986 - the year the UK government launched the controversial AIDS "tombstone" campaign, telling the public "don't die of ignorance" of a virus that could be sexually transmitted.

Decades later, when Paul's full notes were eventually released to the family, it emerged Prof Arthur Bloom - a consultant haematologist - told his GP in 1985 to keep the positive test "confidential".

Mother Pat recalls not being able to talk publicly about her son's declining health

Paul's HIV diagnosis was the beginning of years of secrecy, as the family were fearful of the extreme stigma around those carrying the virus.

Somehow Paul was his "usual self", and met his future wife Monica.

"His life changed because of her support and that was absolutely amazing for him," said Tony.

"Only on one occasion did I feel it had got to him when he discovered he had got hepatitis C as well, in the early 1990s. He said to me, I think the clock's ticking. From that point on, gradually there was a decline in his health."

Pat added: "Friends would say to me, 'is Paul alright? Is he taking the right stuff?' I would poo-poo it and say 'yes it's fine'."

Paul's American wife Monica supported him and is flying to the UK to give evidence to the inquiry

Paul carved a career as a successful architect in Bristol and Cardiff, designing the Huggard homeless hostel among other projects, and he and Monica adopted a daughter in 2006.

Two years later, the hepatitis caused liver cancer and Paul needed a transplant. The operation in Birmingham was successful but he never regained consciousness.

After enduring years of medication for haemophilia, HIV and hepatitis, his heart failed and just before Christmas, a week after the surgery, he died aged 44.

"Nothing can prepare you for watching your son die," said Tony.

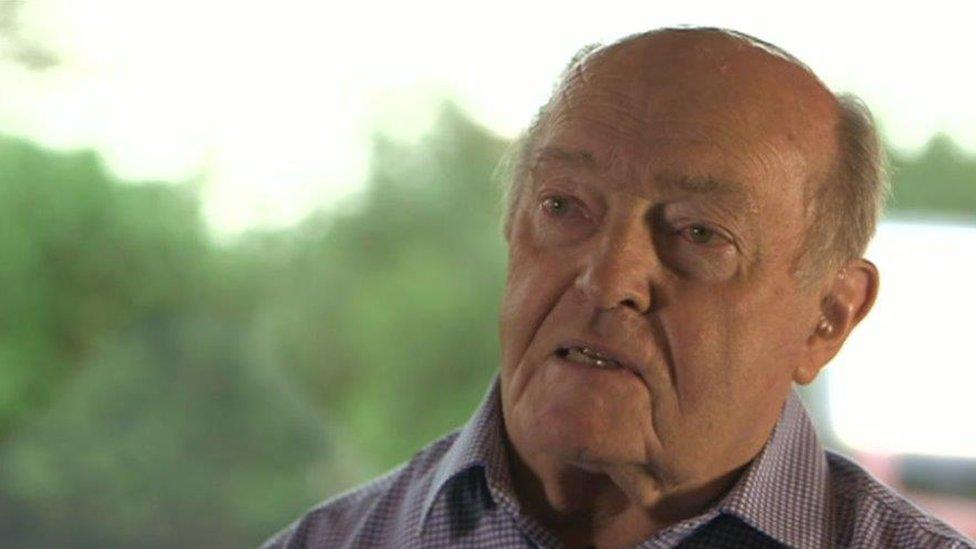

Paul's father Tony says he now wants the truth about his treatment and who was responsible

Paul's family have spent decades investigating what happened, travelling to Westminster to campaign for consistent care for victims, and for the inquiry to which Tony and Monica gave evidence in Cardiff.

They have many unanswered questions, among them whether Paul and others were unknowingly part of a clinical trial, who ultimately decided to keep an HIV positive diagnosis "confidential" from a young man embarking on adulthood and why the family was told for years his medical notes were not available - until they suddenly reappeared.

"Going through those documents, it made me so angry... They had been told 'don't tell him, don't tell anybody'," said Tony, who is now 83.

"The irresponsibility of whole thing from top to bottom, from government, through the NHS, possibly the blood transfusion service... Please tell me the truth. What went wrong?"

- Published22 July 2019

- Published24 July 2019

- Published15 February 2018