Falklands war anniversary: Soldiers' last days at war

- Published

Although the war had ended, some of the veterans found the celebrations back at home difficult

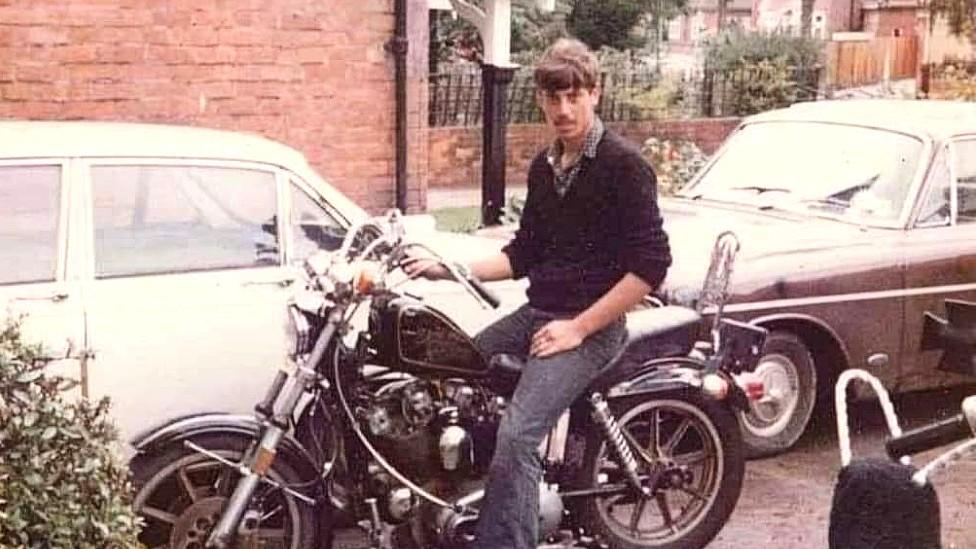

Christopher "Bowser" Thomas was "a bit of a wild character", in the words of his sister, Bernie Mills.

The Cardiff-born soldier had a passion for motorbikes, getting his first one at 16, then having to get rid of it, before getting another at 17 and joining the Hell's Angels when he moved away to Poole in Dorset.

Then came a surprise turn. "He went from being a Hell's Angel to a soldier. It does seem a bit incongruous, but no, he fitted in both very well," said Bernie.

"Nobody in the family can really remember why he decided he was going to be a Welsh Guard. But there was no stopping him, he'd decided and that was it."

Chris "Bowser" Thomas had a love of motorbikes that stayed with him into his army career

Chris joined the Welsh Guards and was a lance corporal when Argentina invaded the Falkland Islands in April 1982, sending thousands of troops to the remote South Atlantic British-held territory.

In keeping with his love of motorbikes, he acted as a dispatch rider once on the islands.

"They actually redistributed some supplies to the different outposts, as well as just messages," explained Bernie.

"Sometimes it's not their stuff that they're redistributing, shall we say, they get around. There's only a few of them. I think what they saw was quite horrific, and what they did was quite horrific."

On 13 June, just one day before the Argentine surrender, Chris was riding with his partner Eric when disaster struck.

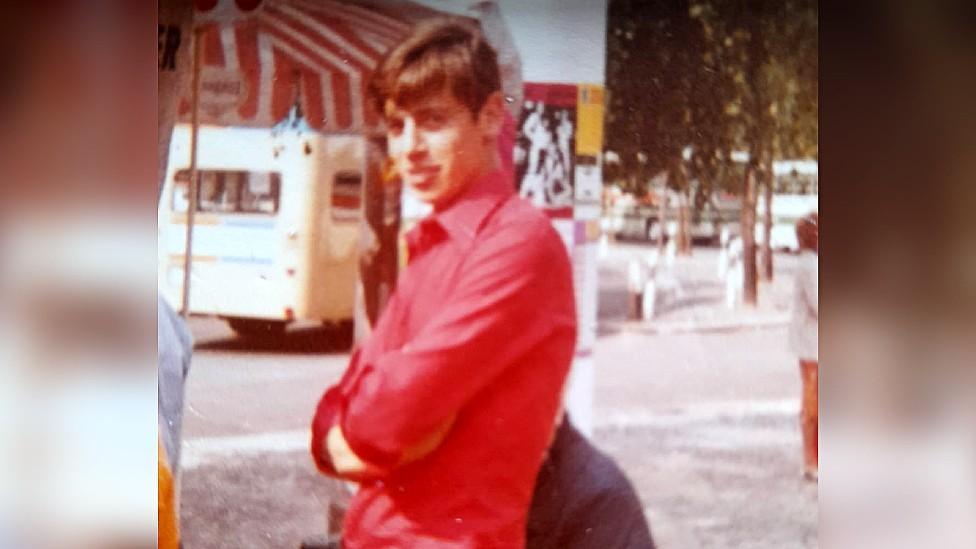

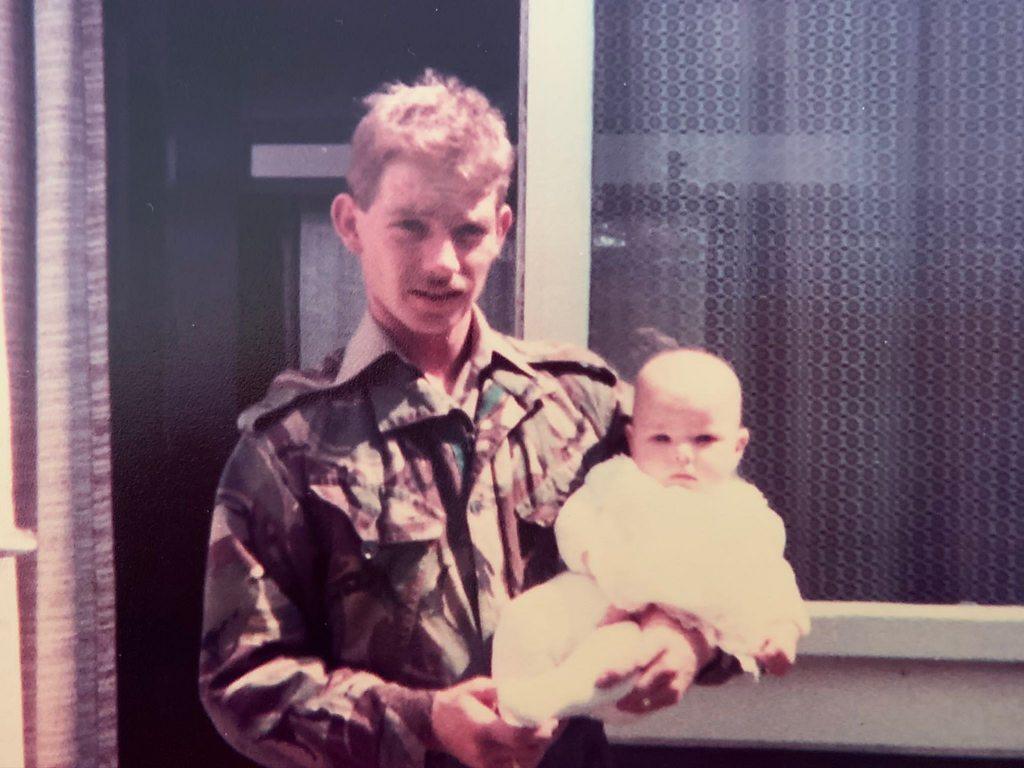

Chris Thomas aged 18 when he signed up for the Welsh Guards

"He was on his bike as part of [regimental sergeant major] Tony's team, and he actually went over a landmine. There was a hole in a road.

"I say road, it wasn't a road, it was a trackway, and Eric went one way and Chris went the other. Eric's OK, Chris isn't."

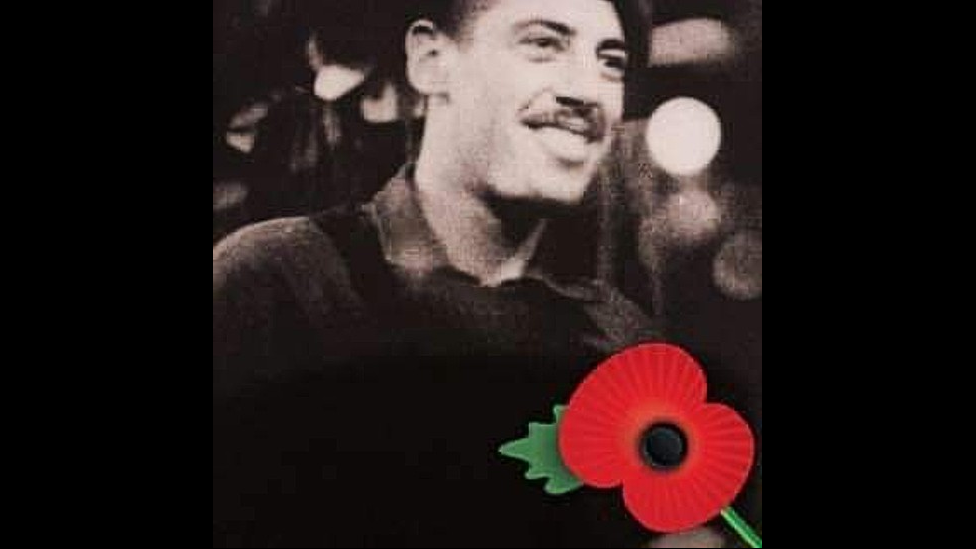

Chris Thomas was one of the last soldiers to die in the Falklands War

Heavily pregnant at the time, Bernie was at home when her husband came back early from work to tell her Chris had been killed, one of the very last soldiers to die in the conflict.

She could not accept the news for a long time. "I always believed somewhere in the back of my mind that he was hiding somewhere," she said. "You know, in a bivouac somewhere. I don't know. But certainly, I didn't believe he died until he came home, until his body came home."

The Welsh Guards suffered the most losses of any regiment in the war. Five days before Chris was killed, 32 other Guardsmen had died on 8 June in the bombing of the support ship Sir Galahad, which was eventually scuttled as a war grave.

Chris was one of the only Welsh Guards whose bodies were returned to the UK for burial.

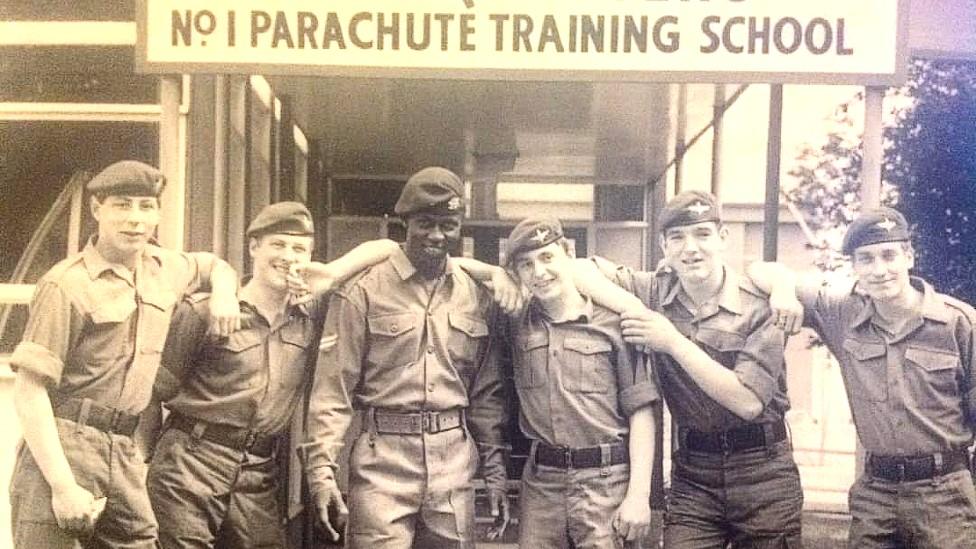

Denzil Connick (second from right) getting his Parachute Regiment wings at RAF Abingdon in 1974

For a fellow lance corporal, Denzil Connick from Blackwood in Caerphilly county, the final days saw him involved in heavy fighting on Mount Longdon with 3 Parachute Regiment, known as 3 Para.

By the morning of 12 June, they had been battling for 12 hours and were coming under heavy shell and mortar fire, which did not let up for another day or more.

"When that daylight came up, the scene was just awful. And it was very eerie as well," he said.

"You could smell the death, you could smell it. And it was kind of a mist floating over the ground as well, and the stillness and the quiet after the noise and the bedlam of battle.

"There's blood-soaked shell dressings lying around; there are corpses of your enemy, the corpses of your friends, you know, just lying there in the stiffened positions which didn't seem real.

"I don't think any one of us had seen such a thing. It had a massive effect on me and I know it had a massive effect on a lot of my friends too - that scene of horror will never, never leave my mind. It was just terrible."

Denzil Connick, pictured aged 25, just before the Falklands war started

As troops prepared to leave Mount Langdon on 13 June, Denzil was taking a map to battalion headquarters on the mount and also "because as a radio operator, I heard there was a resupply of cigarettes".

He had become accustomed to the noise of incoming shells and had learned to judge which were nearby and which were not, but on this occasion he heard nothing before a loud explosion blew him off his feet.

"This shell… just there was zero warning. So therefore it was probably a mortar, and boom, straight away," he said. "All I remember was being thrown in the air and landing on my stomach."

With only two spaces on a medical helicopter, he was judged to be a "no-hoper" but because two soldiers next to him died of their wounds before it could leave, Denzil was taken to Fitzroy field hospital, about half an hour's flight away.

Markers left to two of Denzil's comrades who died on Mount Longdon

"Because of the blood loss, you sort of have a strong feeling that you just want to sleep," he explained.

"When you reach that point, the fear of death seems to go. But what I held on to wasn't so much what was going… to happen to me, but what my death would [mean] …how my mother and father would react to it, my brothers, my close friends, and I thought, 'no, I'm not going to let death take control of this.'

"And I hung on, hung on, hung on."

Denzil's heart stopped and he had to be resuscitated, but the bomb had cost him dearly.

"My wounds were catastrophic… [I had a] traumatic amputation of my left leg.

Denzil Connick lost a leg to the conflict

"The leg that remains, it was just shredded, you know, there was a compound fracture of my femur, and it was sticking out like a flag post.

"The muscle was just torn apart, all over the leg right down to the foot. It was touch and go, whether I could keep that leg, if they could save it."

While Denzil's life hung in the balance, the fighting was continuing.

His comrade in 3 Para, Platoon Sgt Manny Manfred, was in the fighting on Mount Longdon, which he described as one of several features situated in a "defensive horseshoe" around the capital, Stanley, their objective.

The immediate aim was to retake the summit of Mount Longdon from the Argentine forces. The position was being shelled by Royal Navy ships out in the bay.

Manny, from Newcastle Emlyn, which straddles Ceredigion and Carmarthenshire, recalled: "There was lots of noise. In some cases lots of shouting, in some cases lots of screaming when people have been injured. It was difficult to know exactly what was happening in all the confusion of war."

The battle took nine hours, before the Argentine soldiers began to retreat.

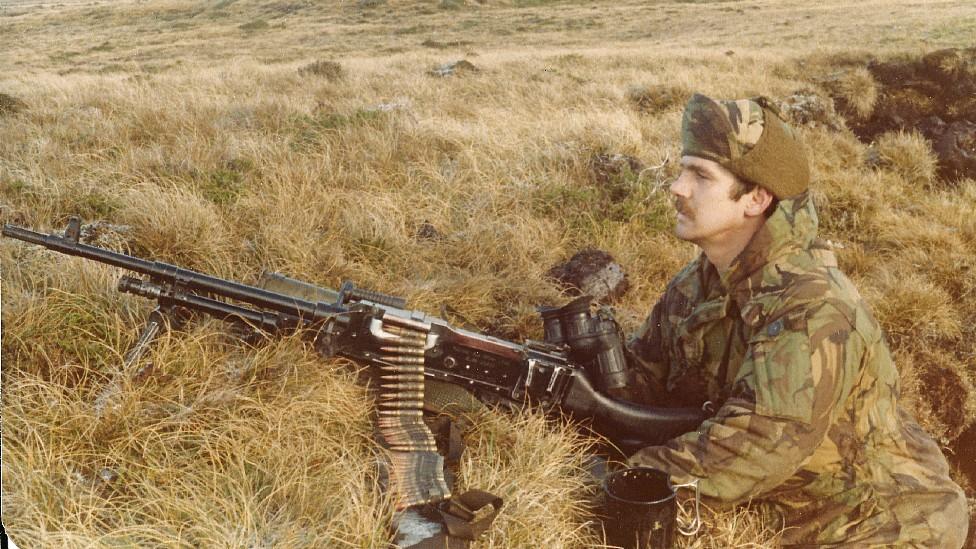

Manny Manfred deployed in the field of combat on the Falklands

"As one or two started to break under the pressure and move backwards, the others thought 'well, we're going to be outflanked, so we better move off'," he explained.

"So as we were moving forward, we would normally have stopped but because we'd broken them and they were effectively running away, we then capitalised on that and move forward to the end of the position.

"At that point, I physically had to stop some of the boys who wanted to run down the hill and chase after them."

They knew once their opponents had reached Stanley, Mount Longdon would come under artillery fire, and that was exactly what happened.

"Any movement could be seen with binoculars from Stanley and they would fire artillery shells at our position. So for the majority of the time, we stayed undercover," Manny said.

"And for the two days after the battle, we were under heavy artillery fire and a further six members of the battalion were killed by artillery during that period."

As word reached them that other positions in the horseshoe had been retaken - names like Tumbledown, and Wireless Ridge - Manny's group was given 30 minutes' notice to advance.

They knew they were going to be moving through a heavily mined area towards Moody Brook, and could see boxes of mines "everywhere", covered over with grass or heather.

Manny Manfred with the red beret he wore on the march into Stanley to claim victory

They followed sheep trails in single file, stepping in the preceding soldier's footsteps where possible to mitigate the risk of triggering a mine.

And it was there, in the midst of a minefield, that word came through the Argentines had surrendered.

"You could see British troops flooding off the features. To our left, Wireless Ridge, 2 Para, our sister battalion; to our right, Mount Tumbledown, Scots Guard, and it was decided that regimental pride dictated we wanted to be the first into Stanley.

"So, helmets came off, red berets came on. Yeah, head down, bum up and into Stanley."

The war was over on 14 June, 74 days after it had begun on 2 April 1982.

But it would cast a long shadow over the lives of those who survived, and those who grieved for the dead.

Denzil said: "Anybody that's been in a war, if you like, on the 'two-way range', where you're firing at someone and someone is firing back.... you are in immensely dangerous situations where loss of life is around you and anybody that's gone through that, it's a life-changing memory that'll stay with you forever.

"We had a job to do, and now we have to carry that with us for the rest of our lives."

Bernie and her family had to wait for five months before Chris's body was returned to the UK.

When his funeral was held, it became a symbolic farewell to all those Welsh Guards and other young men who had sailed 8,000 miles (12,900km) away but had never returned.

Bernie Mills saw lots of families come to her brother's funeral as a way of saying farewell to their own lost men

"I think everyone in the whole battalion was there, just to see him off. It was very important," said Bernie.

"A lot of the people who are lost on the Sir Galahad, a lot of their families came, because it was the only funeral that they could go to.

"There's been memorials since, but at the time, this was what everyone could go to, to say goodbye to their sons, as well as Chris."

She believes the conflict should never have happened, and could have been averted.

"None of them should have died," she asserted. "Surely it should have been sorted out beforehand.

"But I think an awful lot of intelligence was ignored and [it was] just, 'it's only little islands down there in the middle of nowhere that no one's ever heard of. It's not important'.

"Turned out to be massively important, didn't it?"

Ending the Falklands War, a documentary about the last week of the war, is available on BBC iPlayer now.

- Published14 June 2022

- Published8 June 2022

- Published4 April 2022

- Published3 May 2022

- Published11 May 2022

- Published20 January 2022

- Published3 May 2022

- Published20 January 2022