Albion Colliery: The forgotten mining disaster

- Published

It was a coal mine that first created and then devastated a community, and it is also said to be the unlikely setting for a Bee Gees music video. Fifty years after its closure, how does the south Wales community of Cilfynydd remember the Albion Colliery?

"Albion is the forgotten explosion," said Ceri Thompson, curator at Big Pit National Coal Museum.

Much has been reported about the worst mining disaster in UK history, which occurred at Senghenydd, Caerphilly county, in 1913, killing 440 people.

And Mr Thompson said it is often mistakenly believed the second worst in Wales happened at Gresford, Wrexham, in 1930.

But decades earlier, on 23 June 1894, a total of 290 men and boys, external were killed by an explosion at the Albion - 123 horses were also killed.

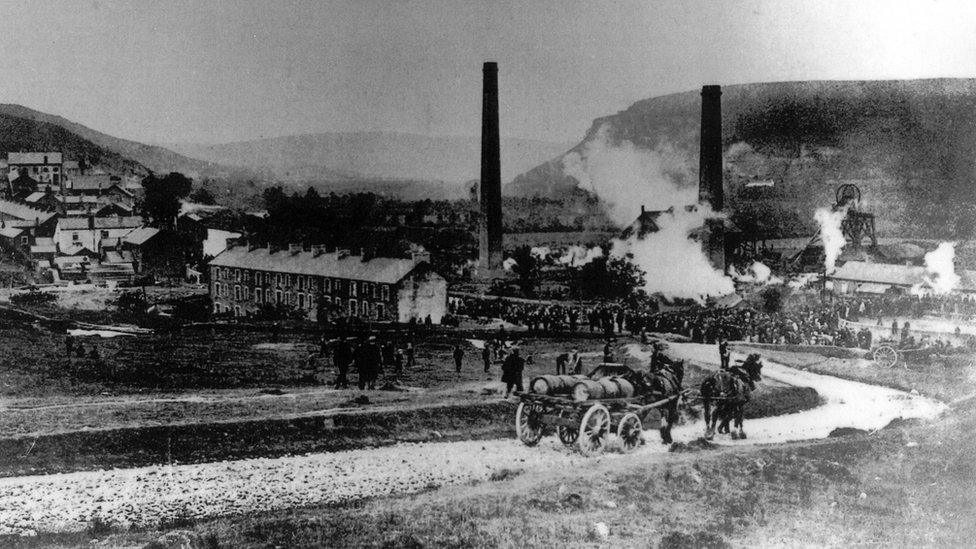

'Ghoulish tourists' joined relatives at the pit head in the aftermath of the explosion

A large number of those who died were from north and west Wales, lodging in the village while working to raise enough money to bring their families to Cilfynydd.

They included the great grandfather of Miss Moneypenny actress Samantha Bond, who discovered the fact while researching her family history for BBC One's Who Do You Think You Are? programme.

"Hardly a house in the village wouldn't have been affected in some way, either by the breadwinner or people lodging there being killed," said David Gwyer, assistant curator at Pontypridd Museum.

"People gathered at the pit head when the news spread, relatives and sightseers turned up en masse.

"Also, a typical thing with so many disasters at the time, there were ghoulish tourists and people who took advantage of that, turning up with barrels of beer to sell."

Eleven of those killed were never identified and a memorial for them now stands at St Mabon's Church, in Llanfabon, near Nelson.

"It knocked the stuffing out of the community. Some people would have moved away if the main breadwinner was lost," Mr Gwyer said.

"But the colliery continued to produce coal. Two or three months after, it was back in full production.

"It stayed at the heart of the community until it closed."

Justyn Jones's great grandfather, Philip Jones, was the pit manager at the time of the explosion and led the rescue that afternoon.

Mr Jones, the director of Small World Productions, made a short film, external with Pontypridd High School - built on top of the old mine site - to mark the 120th anniversary of the disaster.

"It's not just important to my family, it's important for Wales to remember because up to that point it was the worst disaster in Welsh mining history and it's the second worst of all time, yet it's the forgotten one," he said.

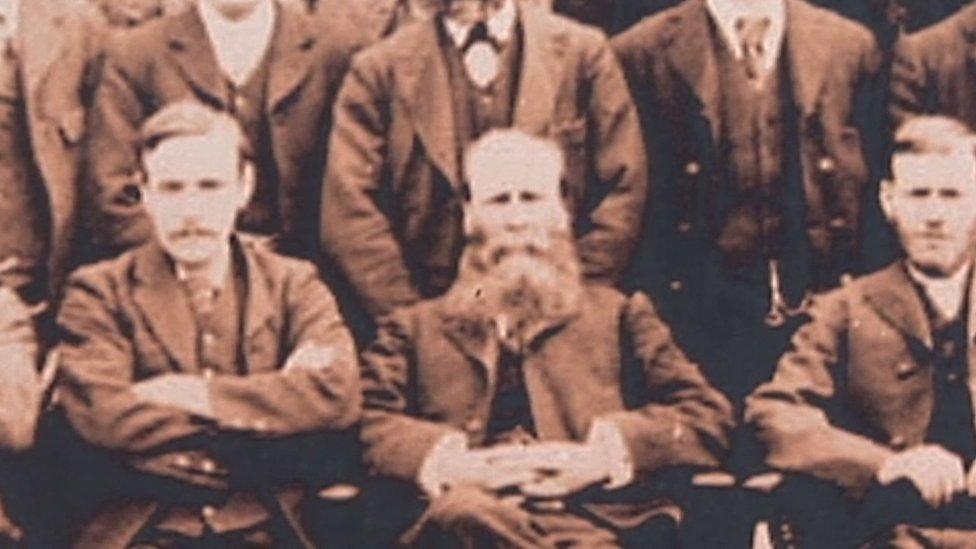

Pit manager Philip Jones (centre) was known as a disciplinarian

The film includes an interview with Mr Jones' late father, Vyvyan Jones, whose own father was a boy at the time of the disaster.

"He was a boy in the garden of the manager's house when they heard something and started running towards the pit head. To have the story told to you is quite a strong part of our family history," said Mr Jones.

In his book about the explosion, One Saturday Afternoon, R Meurig Evans wrote:

"Perhaps the disaster was inevitable. Here was a fiery, dry and dusty mine. Rules were bent if not broken by both men and management it would seem, but it is so easy to criticise ninety years later. One would do well to pause and consider the social and economic conditions that prevailed, conditions which compelled many miners, and others in industry, to cut corners in order to try to improve their lot in life."

An inquest jury found an explosion of gas had occurred, which was accelerated and extended by coal dust igniting, but they could not agree on the origin so nobody was blamed.

The jury did however condemn shot-firing being practised in the mine when the men were at work, without sufficient safety precautions and contrary to rules, although they did not link this directly to the explosion.

This footage of Albion Colliery in action was filmed towards the end of its lifetime.

They also said the under-manager had neglected his duty to ensure the workers stuck to the rules, but the case against William Jones was dismissed because he was "acting" under-manager at the time and it was felt he did not have the same responsibilities.

A charge of "allowing a shot to be fired in such mine in a dry and dusty place" was dismissed against the Albion Steam Coal Company, withdrawn against the agent William Lewis, and not proved against Philip Jones.

But Mr Jones was fined £10, and chargeman William Anstes fined £2, for a lesser charge relating to the storage of explosives.

Justyn Jones said: "There are obviously question marks about how [the explosion] happened. My own personal point of view is [my great grandfather] the manager was a martinet, a very strict disciplinarian.

"But it was a time when you had naked flames down the mine when such places were prone to gas. What could they do? Electricity was only just coming in, they were just about to start wiring it up."

The mine had opened in August 1887.

As with many south Wales pits it sparked the development of a sparsely populated area into an industrial community that was dependent on it.

"The pit is essentially the reason why the village is there, it created it. Before it, there were only a couple of cottages alongside the Glamorganshire Canal," Mr Gwyer said.

"Within a short period of producing coal, there were 3,000 people there who had moved to the district to find work.

"If you look at ordnance survey maps from the early 1880s, there isn't a community there at all. If you look at one from the 1900s, the street pattern is recognisable as it is today."

Six men were also killed during the sinking of the mine and four more were killed by rock fall in the first year. In 1906, another explosion killed a further six men.

But some of those working at the mine towards the end of its life have fond memories of the experience.

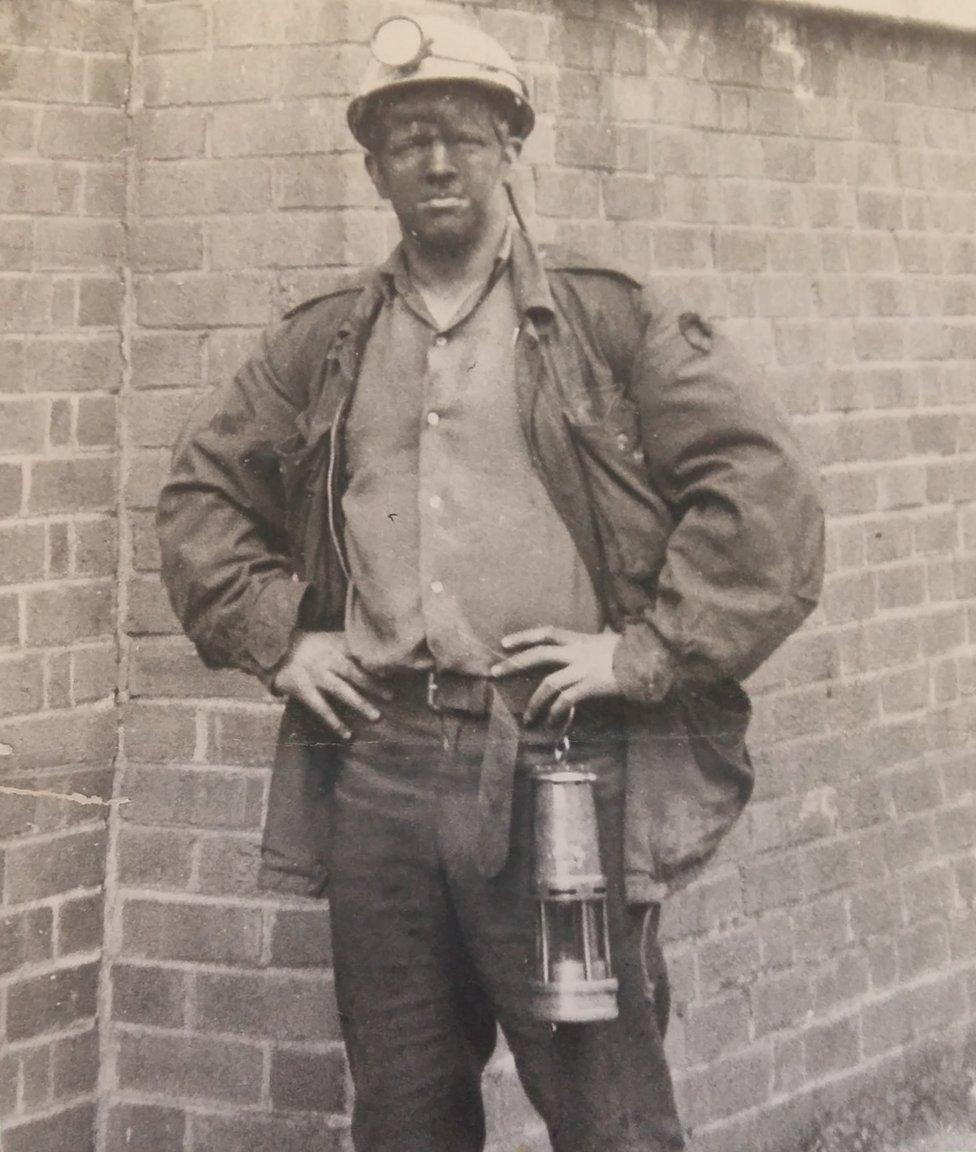

Keith 'Deek' Jones said he was 'distraught' when the pit closure was announced

Keith "Deek" Jones began working at the mine in 1965, aged 17, as an assistant surveyor.

All of his male relatives had worked in the pits and his parents suggested he follow them.

"I absolutely loved it," said Mr Jones, now 69, from Mountain Ash.

"When I was 18, I would get the bus home and then get the bus back down there to join the boys in the Cilfynydd Inn.

"We all met up there on the 21st anniversary of the closure."

He said the reason given for the closure was "adverse geological conditions".

"I was distraught. All heads dropped. Nobody tried too hard after that, they were absolutely gutted.

"Before then, if you had a problem on the face, everyone would come together to help."

He said: "We were all moved to various pits, most went to Deep Navigation, Abercynon or Merthyr Vale.

"The Richard's [pub] closed three months after the pit. It was bound to affect the community, with everybody having to work in different pits."

Vince Melouney (top right) was lead guitarist for The Bee Gees on their first four albums and remembers being filmed at a Welsh coal mine

Mr Jones remembers having to frequently check the tip after the closure, after the colliery spoil tip collapsed in Aberfan, external, killing 116 children and 28 adults.

"I was also involved in filling up the shafts involved with the pit in 1970/71. That was a sad old thing."

He said that while he was there in early 1967, there were some surprise visitors.

"My boss, Cyril Williams, and myself were standing by our office when a minibus drove up with a gang of youngsters.

"One of them jumped out and asked if they could speak to the manager.

"They asked if they could do some filming around the pit to promote a record they were releasing. The manager agreed and we watched them filming for a TV show.

"They told us their name, although it meant nothing to us then. The record was called New York Mining Disaster 1941 and the group was called The Bee Gees - the rest is history."

Marion Adriaensen, who runs a website, external dedicated to The Bee Gees, said Vince Melouney - who briefly joined the band as their lead guitarist in 1967 - recalled filming at a coal mine in Wales for the single.

She said the only surviving Bee Gee, Barry Gibb, and his manager Dick Ashby, said that if they did film at the Albion they unfortunately do not know where the material went as they did not remember ever seeing it.

According to the liner notes for their box-set Tales from the Brothers Gibb, the song was inspired by the Aberfan mining disaster.

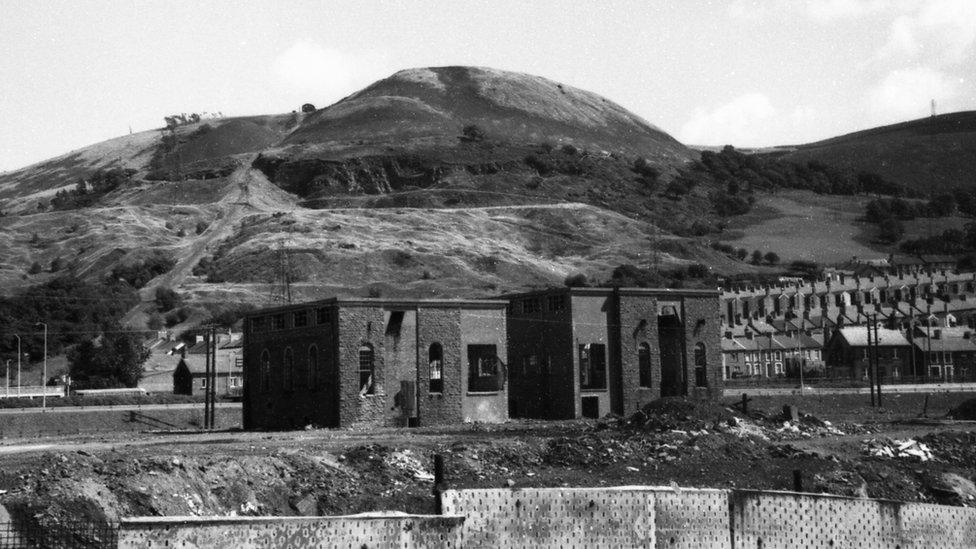

Pontypridd High School now stands where the mine once was

Mr Jones said despite working at many other pits since, and seeing those close too, the Albion was still close to his heart.

So much so, he has spoken to Pontypridd High School - which now stands on the site alongside the Albion industrial estate - about installing a plaque dedicated to those who worked and died there, to mark the anniversary.

"Two hundred and ninety men were killed there. It shouldn't be forgotten," he said

The school, formerly known as Coedylan Comprehensive when it was opened in 1985, has already installed two monuments - a dram where the number one shaft once was and a model of the headgear where the number two shaft was - and it has a "museum" with artefacts from the pit.

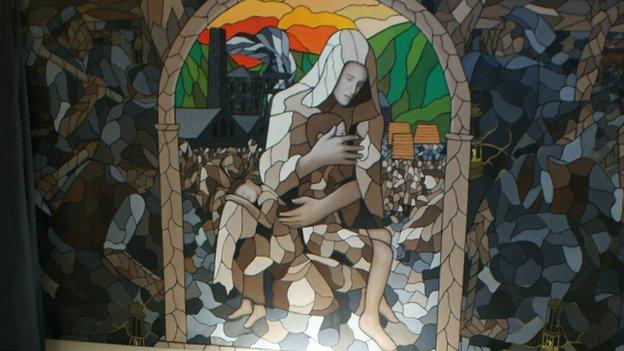

Headteacher Huw Cripps said they would be marking the anniversary later in September, after pupils have returned from their summer break, with the installation of a mosaic in the foyer.

He said they would also be revamping their display of artefacts and memories this year.

"We've done a fair bit to try and maintain the link with the past. There's a massive history to the site.

"We teach a lot about the history of the whole area at our school. Regardless of the disaster, there was a large coal mine here which is a very important part of the jigsaw of what went on from the Beacons to Cardiff Bay."

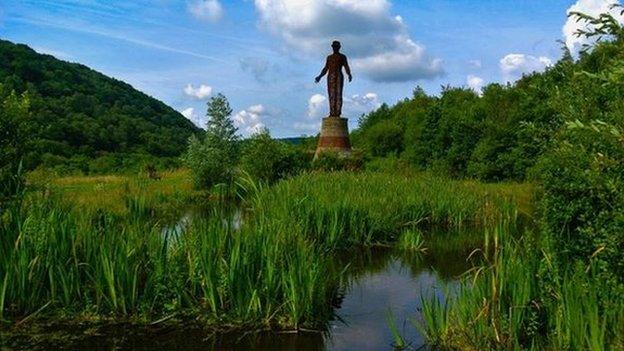

Monuments to remember Albion Colliery in the grounds at Pontypridd High School

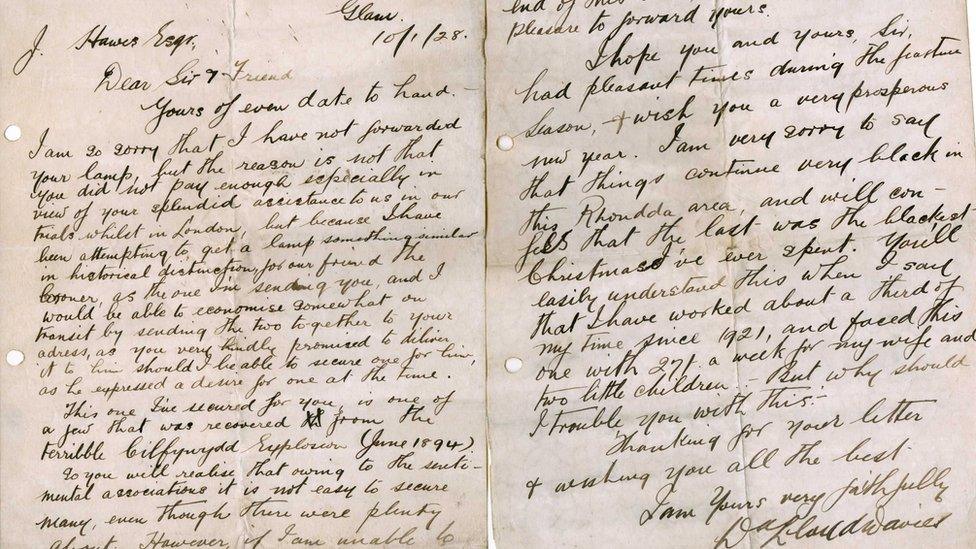

THE LETTER AND THE LAMP

A lamp used in Albion Colliery at the time of the disaster was recently donated to the National Museum Wales after an interesting journey.

Ceri Thompson, curator at Big Pit National Coal Museum, said: "We had it via the granddaughter of an undertaker in London, who acquired the lamp in thanks for his help in the 1927 Hunger March from south Wales."

Hunger marches were a form of social protest in the UK, mostly during the Great Depression. They often involved men and women walking to London from areas of high unemployment, to protest outside parliament.

Mr Thompson said: "On the march each miner carried a lamp and when they got to London there was one knocked over by a bus and another died of pneumonia after a big demonstration in Trafalgar Square in the rain.

"The undertaker helped get the bodies back to south Wales and, in thanks, a gentleman from Maerdy Colliery said he was sending him the historical lamp promised, recovered from the Albion Colliery disaster in 1894.

"This lamp, plus the letter, was donated to the museum by the family three or four months ago.

"The lamp was probably carried by someone who died of afterdamp and just dropped it. The colliery would have collected up the lamps, which were owned by the men not the colliery, and it could have been sent to the man's home

"I can't understand where it was between 1894 and 1927."

- Published23 December 2015

- Published22 December 2015

- Published21 December 2015

- Published6 August 2015

- Published22 September 2014

- Published11 September 2014

- Published12 July 2012

- Published25 May 2012

- Published18 September 2011