2016: The year of anger

- Published

Brazil President Dilma Rousseff was among several leaders to face fury from their public

Does one emotion above all hold the key to understanding a year of tumultuous political change?

I got it from both sides: eardrum-denting yells of fury, which managed to break through the noise of surrounding protestors.

This was April in Brazil, with the country's President Dilma Rousseff facing what would eventually be a successful attempt to impeach her. Both opponents and defenders had taken to the streets.

"Go Dilma, go! Never more… NE-VER Mooooooore!" screamed one man.

Just in case you might miss the fervour of his opinion, two fellow protestors marched, bearing a coffin with the president's name on it. Yet only a short distance away I found supporters of Dilma Rousseff roused to equal passion.

One screwed his face up tight, as if mustering all the wrath of which he was capable, and then detonated it in a blast of fury which at one point threatened to overwhelm the limits of my microphone.

"Dilma cares for the poor. Every time a movement for the poor gets going, then comes a coup d'etat… violence is their game. We need radical resistance!"

Many of Donald Trump's supporters were keen to show their dislike of Hillary Clinton

It was just one scene from 2016, a year defined by the unexpected, the unpredicted and unprecedented. Yet it was also a year in which one emotion was cited as the driving force behind these developments.

"There is great anger out there," Donald Trump told a rally, in what paradoxically was one of his calmer campaign speeches. "Believe me there is great anger."

He might perhaps have been looking at his own supporters, who wore anti-Hillary T-shirts with slogans like "Trump that Bitch".

More on a year of anger

Mr Trump was speaking of a subject which he knows first-hand, being an enthusiastic sender of angry nocturnal tweets.

Indeed, both supporters and detractors see Donald Trump's victory as a tribute to his knack for understanding people's discontent, then channelling it.

"Trump gave anger the green light," argues Arlie Hochshild, a sociologist based at the University of California.

She believes many of his supporters were fired up by resentment at a globalised economy which seemed to have passed them by, their wages stagnant, the promise of the American dream unfulfilled.

"Trump," she says, "gave permission for them to express what they had been storing."

Sometimes the very language of politics seemed to betray the aggressive emotions beneath.

When Britain voted to leave the European Union in June, this was described as "giving the establishment a bloody nose" or "a slap in the face for Europe's elites" .

Beppe Grillo led the successful No campaign in Italy's referendum on constitutional change

These political slaps were not just a Western phenomenon. In South Africa and South Korea, in Hong Kong and Venezuela, angry crowds gathered to protest in 2016, not against a particular government, but against the very system by which they ruled.

Perhaps the prevailing mood was best summed up by the Italian comedian-turned-politician, Beppe Grillo, who successfully campaigned for his country to vote No in a referendum on constitutional change.

"No," Mr Grillo said, was the most beautiful thing to say in politics these days, adding an obscenity directed at anyone who disagreed with him.

If anger generated political upsets in 2016, then, according to the psychologist, Oliver James, anger was also an understandable response from those on the losing side, like EU Remain campaigners in Britain.

Their defeat in a referendum, he suggests, was experienced like bereavement.

"We go through a cycle of sadness, despair, but then at other times are swamped by very powerful anger," James explains.

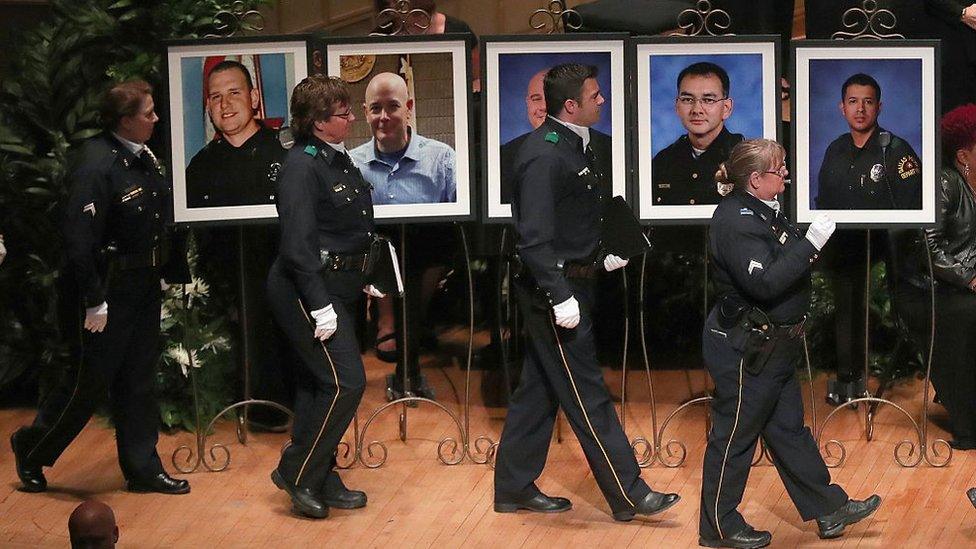

I saw that sequence at work in Dallas this year, after five police officers were shot dead by an African-American army veteran. At a makeshift shrine, local residents expressed their shock, but many were also furious that this could happen, that the very people tasked with protecting them could prove so vulnerable.

Five police officers were shot dead by an African-American army veteran in Dallas in July 2016

Yet the most pessimistic assessment came from a fellow African-American, who told me that while he could never condone the killing, he certainly understood it.

"Black people are tired of the way police officers treat us," he explained. "I don't think it's going to calm down. I think the fire is already lit for retaliation."

That cycle of violence, the perpetuation of anger: this is what the writer Sam Leith fears will be the legacy of 2016.

We are abandoning, he believes, the Greek ideal of logos (or reason) and ceding ground to the more irrational potential of pathos, expressed for now as anger.

"Anger seeks an object," he argues, "it's very Newtonian. There's action and reaction, a divisive process which continues to accelerate divisions… some sort of slow-motion catastrophe is what's required to press reset."

Yet this presumes that a reset is being sought in 2017, whereas the political changes unleashed this past year were welcomed by many as merely the beginning.

Nigel Farage, one of the key campaigners for Brexit, offered a pertinent prediction.

"For those of you who aren't particularly happy with what happened in 2016, I've got some really bad news for you - it's going to get a bloody sight worse."

- Published27 December 2016

- Published28 December 2016

- Published24 December 2016