How do you start a country?

- Published

On 1 October, Catalonia held an unofficial vote to determine whether or not the region should break away from Spain to become an independent state.

It is not the first time that such a region has sought independence.

But what things do you need to become an independent state?

BBC World Service's The Inquiry has looked into how it might work.

The four characteristics

"You can't be a real country unless you have a beer and an airline." So said the rock musician Frank Zappa.

But actually, international law experts are much more likely to identify four main facets of a state: a people, a territory, a government, and the ability to conduct relations with other states on a sovereign basis.

The definition of a people is much disputed, but some might argue that it means a permanent population with a concept of, and belief in, their own nationality.

As James Irving, who teaches international law at the London School of Economics (LSE), puts it: "Are there... ties, effective ties, ties of belonging, of identity of feeling."

"And also, ties relating to those of practical shared interest."

Another essential is that states should have a defined territory, an area within borders, in which it is sovereign.

Stable and effective government is another criterion of statehood cited by many.

The ability to conduct relations with other states is another key element.

So sovereign states are free to enter into relations which are bilateral - where, for example, two countries agree to diplomatic relations or work together to solve a common problem - or multilateral - as part of the EU, for instance, or as signatories to international climate change agreements.

Underlying this is the understanding that a sovereign state is neither dependent on, nor subjected to, any other power or state.

So how do would-be states become true states?

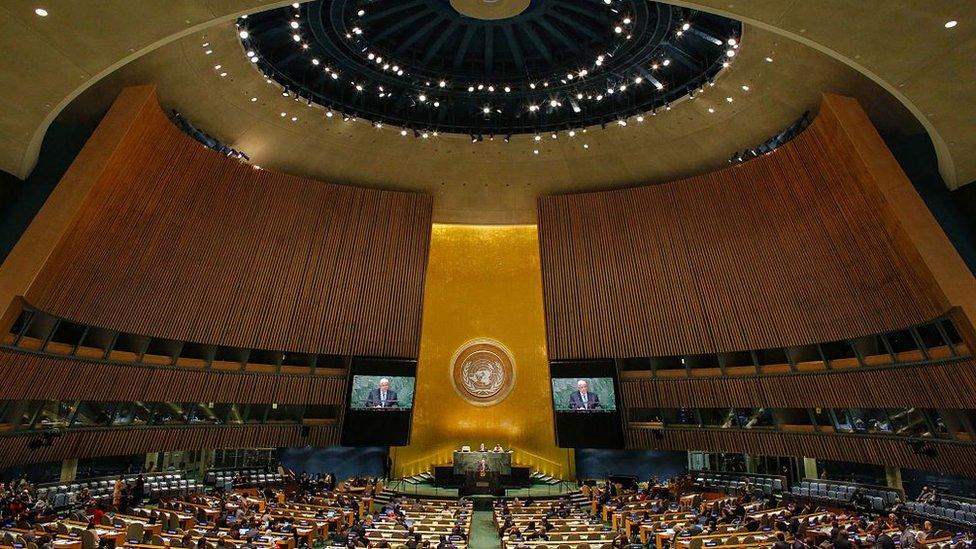

Recognition as a sovereign state by the United Nations is the ultimate prize

Recognition

Individual countries can recognise each other, but the big prize is recognition as a state by the United Nations.

The benefits are legion: The protection of international law; access to loans from the World Bank and the IMF; control over borders and greater access to economic networks; and mechanisms.

Plus the protection afforded by trade laws, making it easier to create trade agreements.

But can you be unrecognised by the UN and still be a state?

"Essentially, it's the old adage: if it walks like a duck and talks like a duck, it is a duck," explains Rebecca Richards, a lecturer in International Relations at Keele University.

"We recognise that it is state-like, it's just lacking that recognition."

People in Somaliland celebrate the anniversary of the country's declaration of independence

Somaliland is a case in point.

A former British protectorate in East Africa, it was independent for four days in 1960, before it joined up with Italian Somalia.

It remained part of Somalia until the government there collapsed in 1991.

Then Somaliland unilaterally declared independence.

"There's a remarkably strong government," explains Rebecca Richards.

"It's had a series of democratic elections. It's peaceful. It's stable. There's an incredible amount of economic development that's taking place. It's pretty much everything that you would expect to see in a state," Dr Richards adds.

But Somaliland is not recognised by anybody, making life hard.

"There is limited access to some types of developmental assistance or humanitarian assistance, but a lot of that, especially… aid that comes from the UN… goes through Somalia."

Access to international markets is difficult without legal protections.

As Somaliland's currency is not recognised outside its boundaries, it has no international value.

Legal barriers

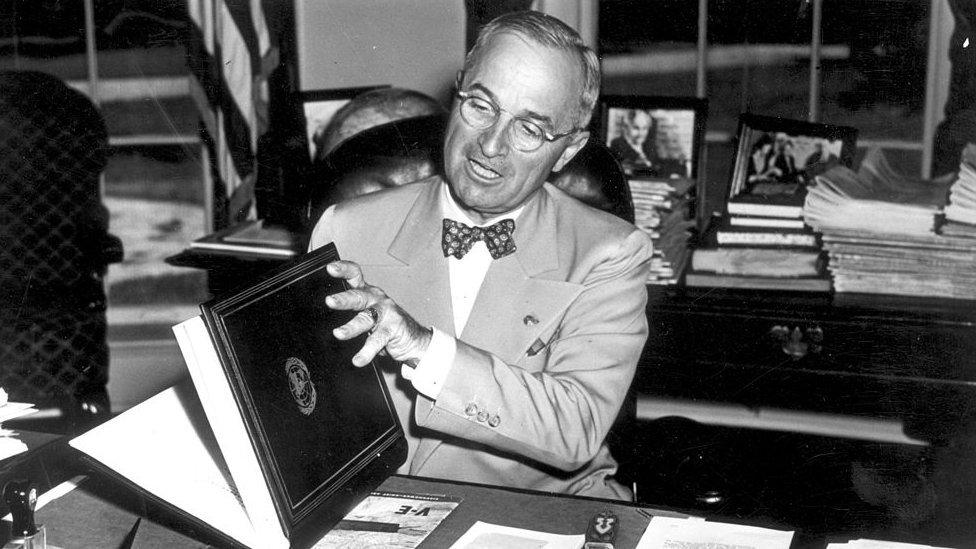

US President Harry S Truman examining the United Nations Charter in Washington in 1945

The concept which underlies the idea of a nation state is "self-determination".

The Oxford English Dictionary defines it as: "The action of a people in deciding its own form of government; free determination of statehood, postulated as a right."

This right was enshrined in the UN Charter in June 1945.

Self-determination was initially seen as a way for peoples living under colonial regimes to gain independence, or choose some form of association with the former colonial power or another state.

"A lot of people thought it sounded like a good idea," explains Dr Irving, "but there wasn't a great deal of agreement on what it meant."

If the people of a colonised territory wanted their own country, the principle of self-determination suggested they should have it.

About a third of the planet's population saw its political status changed.

From just 51 countries in 1945, the United Nations today has 193 members.

But there was a catch.

Many jurists of international law maintained that after a colony gained independence, further separations, or consideration of changes in borders, were out.

But this runs up against the idea of self-determination.

"How do you marry those two principles, that borders can't change and yet people should have a right to determine their own future?" asks James Ker-Lindsay, senior research fellow in South East European Politics at the LSE.

Autonomy

Kosovo took part in the 2016 Olympics, but does not have full international recognition

The solution was to say that, for people living inside the borders of the country from which they want independence, self-determination gives a right to autonomy, but stops short of being allowed their own country.

This issue came to the fore in Kosovo.

When Yugoslavia broke up, it was replaced by six republics, one of which was Serbia.

Kosovo was a province within Serbia's borders, but with a different ethnic population which had enjoyed a large degree of autonomy.

Kosovo becoming independent would have changed the borders of Serbia and violated the principle of territorial integrity.

"The international community's first response was to say [Kosovo] should have a right of internal self-determination," says Dr Ker-Lindsay.

"[That] this is a province of Serbia but they don't have the same right to independence that the other republics had.

"So once [the Kosovans] realised that they weren't going to get independence through peaceful means, they launched an uprising," he adds.

A conflict with the Serbian authorities followed, which only ended with Nato military intervention in 1999.

Then in 2008, Kosovo unilaterally declared independence.

Serbia said this was invalid and took the issue to the court of the United Nations that settles international legal disputes - the International Court of Justice.

"The question put before it was, was Kosovo's declaration of independence in contravention of general international law?" says Dr Ker-Lindsay.

"And the court actually said there's nothing under international law that says a territory can't declare independence."

But the crux of the matter was less a question of law and more whether Kosovan statehood was likely to be recognised.

"Kosovo has been recognised by more than half of the UN members," says Dr Richards, "but it's still not recognised as a sovereign state because the UN, as a body, does not recognise it as a sovereign state."

And some recognition means Kosovo enjoys some of the benefits of being a state such as access to the World Bank, the IMF, and the International Olympic Committee.

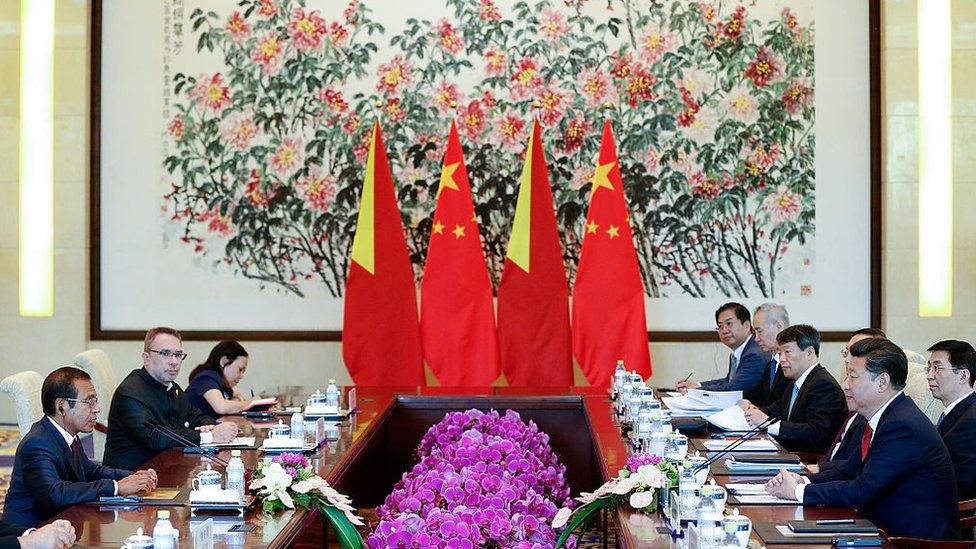

East Timor President Taur Matan Ruak (l) met China's President Xi Jinping (r) in Beijing in 2015

Powerful friends

"It's essentially impossible for a group to become independent and claim its own statehood unless others, other powerful states, are willing to support it," says Milena Sterio, a professor at Cleveland State University in the US, where she teaches international law.

So what does it take to get the great powers to back you?

East Timor was a Portuguese colony until the 1960s, when it was invaded by Indonesia.

The Indonesians were a valuable US ally during the Cold War, so the East Timorese independence movement received little support.

It wasn't until after the Cold War, in the 1990s, when international attention turned to East Timor again and the western great powers no longer needed Indonesia as an ally because communism had fallen.

"The western great powers, essentially embarrassed by the human rights violations that were taking place in East Timor, backed off and essentially said, 'OK, now you the people of East Timor, you get to exercise this delayed right to self-determination,'" say Prof Sterio.

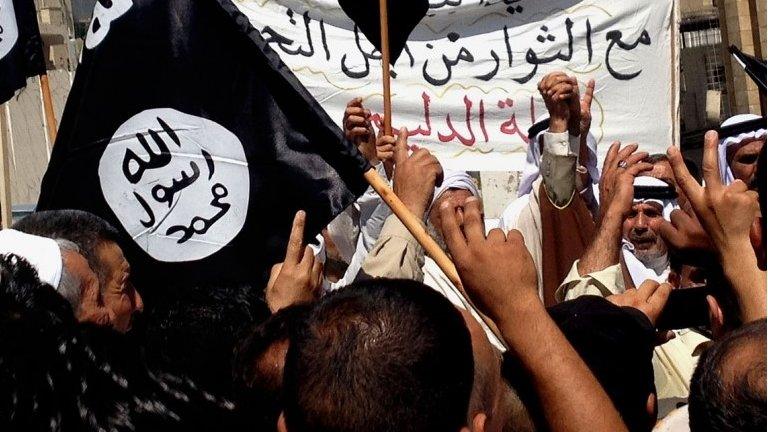

Catalonia has a highly active independence movement

In 1999 the Timorese voted for independence, which they got in 2002.

But the process was marred by violence, and needed political support from the UN and the intervention of international peace-keepers.

The situation in Spain is very different.

Under current principles of international law, the Catalans have a right to self-determination, but many jurists would argue that all they can hope for is autonomy, not independence, because of Spain's right to maintain its territorial integrity.

So what happens with a vote in favour independence?

"I really foresee a negotiated solution where Catalonia remains in Spain with perhaps a heightened degree of autonomy," says Prof Sterio.

"What's really interesting is that Spain is one of the Western democracies that has actually not recognised Kosovo as an independent state because Spain is afraid of establishing this independence-seeking precedent because of Catalonia threatening the territorial integrity of Spain."

And although the situation of the Kurds is very different, ultimately they will run up against the same problem - a lack of great power support.

The Inquiry: Who gets to have their own country? is now available via BBC iPlayer or the programme podcast.

- Published6 January 2015