World Cup 2018: Why millions of fans see the football like this

- Published

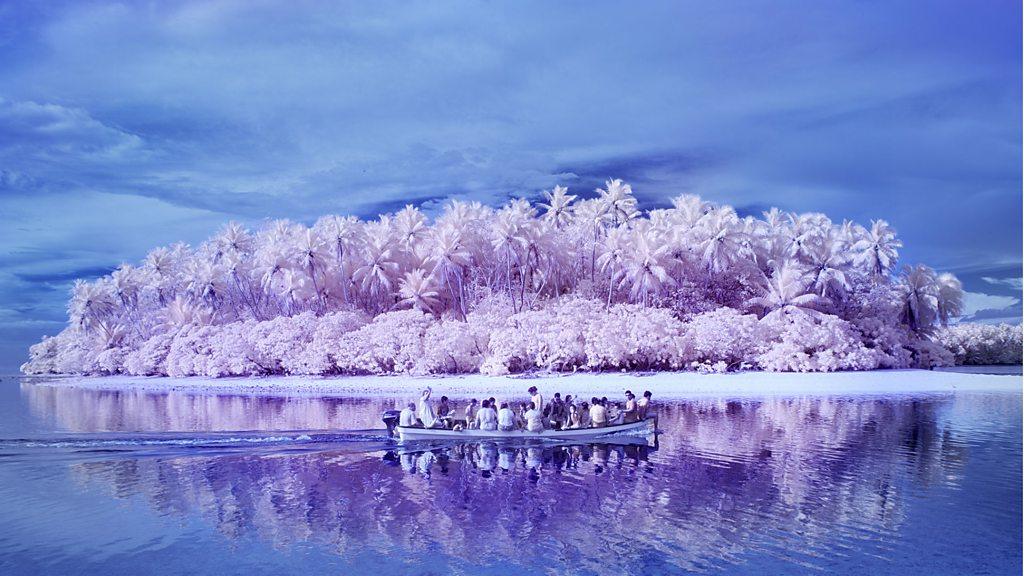

A colour-blind simulation created by Colour Blind Awareness

Sean Hargrave is a self-declared football obsessive, but when he sat down to watch the opening match of the 2018 World Cup he couldn't tell one team from the other.

He wasn't the only one struggling. Roars of frustration jumped from sitting rooms to social media as fans worldwide branded Russia v Saudi Arabia "a disgrace".

The problem? Sean, like 1 in 12 men and 1 in 200 women, is colour-blind.

Specifically, he struggles to tell red and green apart - the most common form of the condition. So if one team plays in red kit (Russia) and one in green (Saudi), it's game over. Or as he puts it, "it's like Madonna coming out on stage and saying, 'I'm singing the songs in Swahili tonight!'"

Colour-blindness varies in type and severity, but to someone with severe red-green issues, watching Russia demolish Saudi Arabia might have looked a bit like this:

Simulation by Colour Blind Awareness

Instead of like this:

A massive 320 million people worldwide are colour-blind. Statistically, the condition affects one player in every men's football team. And with almost half the planet projected to watch the World Cup, many are furious that its organiser Fifa has failed to take account of what they can and can't see.

Allow Facebook content?

This article contains content provided by Facebook. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read Meta’s Facebook cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

'I can see Brazil and the ball...'

The most obvious liability for colour-blind people is not being able to tell football strips apart, especially in a fast-moving game.

It might be that the teams' main kits look too similar - or that a goalkeeper or referee's shirt makes him look like an outfield player.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

As well as the classic red-green confusion (which also cropped up in the South Korea v Germany game), colour-blind people may struggle to distinguish between:

Reds, oranges, yellows, greens and browns

Red and black

Blues, purples and dark pink

Senegal and Colombia played each other in green and yellow, which was tricky for some fans. And the same happened with England v Sweden, where they couldn't tell England goalie Jordan Pickford's lime green kit apart from Sweden's sunshine shade.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Any game that goes to penalties prompts major frustration too, thanks to the red and green blobs which show TV viewers the nail-biting tally. Unless you're red-green colour-blind, in which case...

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Katy Moran, 27, who is colour-blind and plays for Aston Villa Ladies, told the BBC she sometimes has to stare at the players' socks to work out who's who - including when she's on the pitch herself.

"We played Millwall last season. Villa wear a claret colour and Millwall had... it must have been dark blue. They walked onto the pitch, I looked and thought - good job I'm not playing! And both teams had white shorts on as well."

Inevitably, it damages her game. "You're concentrating on trying to work out who's who. If I was playing [Millwall] my reactions would be so much slower, because I can't work out quick enough if it's my player who's about to get the ball, or if I should step in.

"There have been times when we've played with red cones and I've moved out of the area because I couldn't see where they were. I was running off and they're like, 'Where are you going?!'"

Katy Moran of Aston Villa Ladies says she struggles to watch around 1 in 5 football matches on TV, due to her colour-blindness

These are problems that reach football's highest levels - including players taking part in the World Cup.

Just eight minutes before meeting the Danish international team to fly to Russia, midfielder Thomas Delaney phoned a Danish radio station to support a colour-blind caller who said he'd had trouble telling Denmark and Mexico apart in a pre-World Cup friendly, external.

Giving his name only as "Thomas", Delaney told the station DR P3: "I'm red-green [colour-blind]. I wouldn't say it's too bad, but it does happen. The other day on the field it was a bit difficult, seeing who was on my team and who was on the other."

"And do you play for a red or a green team?" the hosts enquired.

"I play for the red team," he said.

"What team do you play for, Thomas?"

"The Danish national team."

Thomas Delaney (front row, first from right) pictured with the Denmark starting XI in their white away kit, ahead of their game against Australia

Delaney's frank admission saw both Denmark and Australia don their away kits when they met for a 1-1 draw in Group C. According to the Totally Football Show podcast, Australia's dark green was easier for the player to distinguish from white than their usual yellow.

Kathyrn Albany-Ward, founder of advocacy group Colour Blind Awareness, says the Dane's honesty was a threshold moment.

"He is the first ever player at elite level, still playing, that we know of who has spoken out about being colour-blind. I don't think he realises the implications of what he's done," she says.

"Most people don't speak out because they're frightened that it's going to affect their value; whether they get played or if they're put on the bench, and all that kind of thing. It shouldn't, but that's what they'll be frightened of."

Thomas Delaney of Denmark and Borussia Dortmund told the radio station DR P3 he wanted their previous colour-blind caller to know he wasn't alone

The nervousness is understandable, given the tendency of opposing fans to leap on any perceived weakness. "That was never a red card, ref must be colour-blind!" is standard chat at grounds.

Adrian Smith, 60, is a British amateur referee who qualified in 1978 - and describes himself as "manageably" red-green colour-blind. He referees in his local youth league in Gloucester, and reckons pitfalls can often be avoided with a bit of pre-match planning.

Organised competitions usually have a handbook which lists the colours teams are registered to play in, he says.

And if they wear something different on the day?

"Then you can ask the team captain before you toss the coin at the start of the game, 'That's a nice kit - what shade would you describe that as?' That's a strategy that works for me."

Hoping for better at Euro 2020

Social media has given colour-blind football fans a platform to share their experiences, both with each other and the world at large.

It's underscored how much still needs to change - and activists are working hard to make the game more accessible before the next major contest.

Colour Blind Awareness has spent the last nine months auditing the stadia that will be used for the 2020 Uefa European Football Championship, and flagging up less noticeable colour-blindness issues. Signage, for example: Exit signs, safety warnings and directions can effectively be invisible to some if they're mounted on the wrong colour background.

Last year, the group also worked with the English Football Association (FA) and Uefa to produce guidance notes on colour-blindness, external, and how to improve all areas of football for people with the condition. According to the FA, it is the only Uefa member to do so.

Ms Albany-Ward says the FA wants to protect younger players, "to make sure they aren't being discriminated against if they aren't performing as well as they could".

Some British Premiership clubs are becoming more accessible too. Tottenham Hotspur designed its website and season-ticket pricing plan to be less confusing for colour-blind fans, who frequently despair over online ticketing systems that use colour-coding to show where seats are, or which are available.

Colour-blind fans have an extra reason to cheer premiership team Tottenham Hotspur

With early signs of progress on the horizon, is there hope that the next World Cup, in 2022, might finally be colour-blind-friendly?

"I know Fifa are aware of it on some level," says Ms Albany-Ward. "I don't know how high up. But they should be aware of the Uefa guidance, external.

"They have been looking at other visual impairments - they've been doing special commentary for blind people, and a lot for hearing-impaired people. So colour-blind people are next on the list, I would hope!

"Colour-blindness affects far more than the people in the stadium. It's millions of people worldwide - and they've missed a trick really. They could have avoided the adverse publicity that they've had if they'd just been a bit braver, and thought about it a bit sooner."

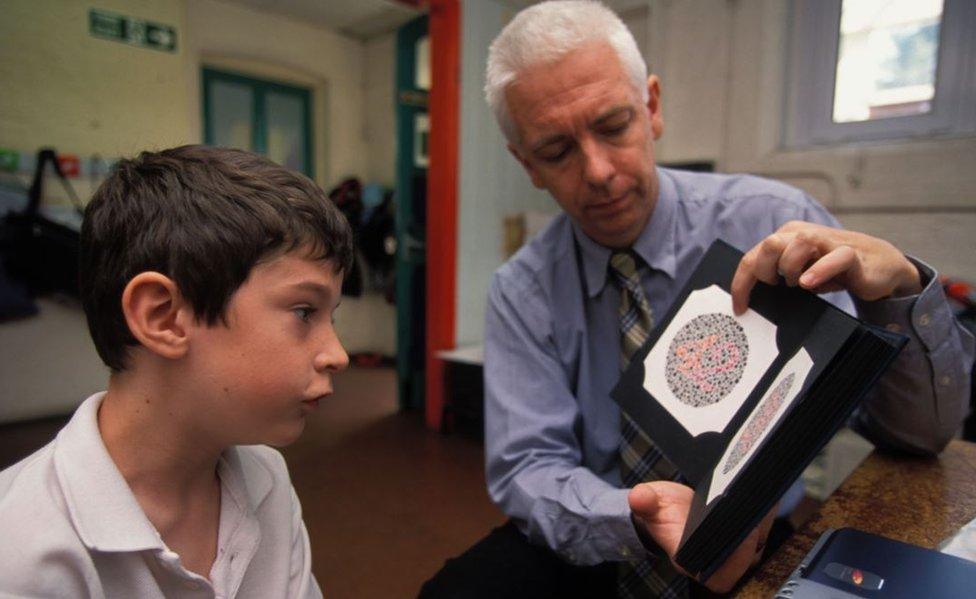

How colour-blindness happens, and how to get tested:

Why are people colour-blind?

Colour-blindness is usually inherited, and is believed to be passed down the maternal line.

However, some people get it through a health condition, including diabetes or multiple sclerosis - or as a side-effect from certain medications.

What causes it?

Humans see colour through nerve cells in our eyes, called cones. There are three separate kinds, which absorb red, green and blue light. A fully functioning set will allow you to see the full colour spectrum.

But in someone colour-blind, one type of cone cell is faulty, or (in severe cases) does not exist at all. If it's the red cone, the person will struggle to see colours that contain red clearly. So they might confuse a blue and a purple because they can't "see" the red component of purple, for example.

Simple tests are available to establish whether someone has abnormal colour vision

There is no cure for inherited colour blindness, but the acquired kind can sometimes be reversed.

Many people who are mildly colour-blind don't realise that they are, because they were born with the condition and don't realise others are seeing a fuller range of colours.

What should you do if you think you might be colour-blind?

Visit a local optician, and ask for a colour vision test. You might also find it helpful to speak to your GP.

There are initial tests you can take online, external - though these shouldn't replace a proper diagnosis.

Support and advice are available from:

The NHS, which has this online primer on the basics, external

Colour Blind Awareness (UK-based), which has guidance for businesses, parents and teachers, external

- Published9 July 2018

- Attribution

- Published8 July 2018

- Published23 July 2017

- Published28 September 2015

- Published17 February 2015

- Published21 June 2014

- Published17 April 2011