Strasbourg shooting: Why known extremists can carry out terror attacks

- Published

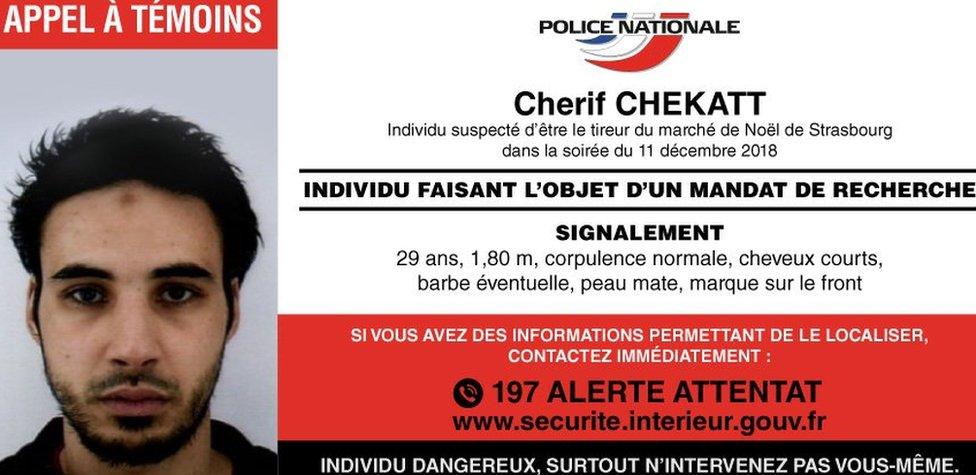

The gunman who killed three people in Strasbourg's Christmas Market had been radicalised in prison, French authorities say.

Sadly, the reality that they were aware of Cherif Chekatt, but unable to prevent the attack, follows a pattern seen in other countries.

At George Washington University, we have looked at 76 jihadist attacks in Western Europe and North America in recent years. We found that more than half involved perpetrators who had been on a security service watch list.

In France alone, the examples are plentiful.

Authorities had monitored the Kouachi brothers, who killed 12 people in at attack on the satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo, in January 2015.

They were also aware of Amedy Coulibaly who, shortly afterwards, shot dead female police officer Clarissa Jean-Philippe before killing four people in a Jewish supermarket.

Three of the attackers at the Bataclan theatre in November 2015 - where 90 people were killed - were known, as were at least eight other individuals who have carried out attacks in France since 2015.

In the UK, some of those responsible for the Westminster and London Bridge attacks, which killed 13 people and injured many more, were known to the authorities.

It is a similar story in other Western countries hit by jihadist attacks, including Germany, the Scandinavian nations and the US.

Tactical mistakes

The news that perpetrators were already known to authorities inevitably raises questions. Why didn't the security services intervene in time?

Indeed, some reviews of counter-terrorism operations after an attack do reveal shortcomings and tactical mistakes.

For example, in the UK a review of the attacks carried out in 2017 said the MI5 security service had missed a chance to monitor Salman Abedi, external, who killed 22 people at an Ariana Grande concert at Manchester Arena.

Salman Abedi killed 22 people in the bombing at Manchester Arena in May 2017

But the actions of Western intelligence and law enforcement agencies are limited by a number of factors.

This helps explain why individuals who are well-known to authorities as "radicalised" are free to remain part of society and, at times, go on to carry out attacks.

The exact reasons vary from country to country, but two key overlapping factors prevent authorities from "doing something" about known radicals.

Firstly, legal protections in Western democracies prevent authorities from arresting individuals because of their beliefs.

There is a right to be a radical and to voice views that are aberrant to the majority.

Unlike in authoritarian regimes, expressing such views is not normally against the law.

However, in some circumstances - cases which are often difficult to prove - those expressing radical views can be guilty of incitement, recruitment, or hate crimes. In the UK, for example, radical preacher Anjem Choudary was jailed for inviting support for the Islamic State group.

Instead, what authorities can do when they identify a radicalised person is monitor them.

Even if they receive the court orders often needed for surveillance, law enforcement and intelligence officials run into the second problem: scarce resources.

The French experience, albeit more pronounced than that of all other Western countries, perfectly encapsulates this challenge.

Hundreds of police were involved in the search for Cherif Chekatt in Strasbourg

French authorities currently list more than 20,000 individuals as Fiche S, the category used to denote radicalised individuals. This list included Cherif Chekatt, who was shot dead by police after they encountered him on a Strasbourg street on Thursday evening.

But to monitor all these people poses an insurmountable challenge. Round-the-clock, intensive surveillance of a suspect normally requires about 25 officials on any given day. 24/7 surveillance on all 20,000 Fiche S subjects would require half a million intelligence officials.

In the UK, MI5 says it is running "well over 500 live operations involving about 3,000 people known to be involved in extremist activity in some way". About 20,000 people have been part of its priority investigations since 2009, but are no longer believed to be a threat.

Because of the numbers involved, authorities divide the suspects into tiers, according to an assessment of their propensity for committing violence and allocate resources accordingly.

In most cases, their assessment is correct, but we seldom hear about it.

When their assessment fails, the result can be an attack.

Sudden and unpredictable

Western authorities constantly struggle with how to deal with individuals in this grey area: those who are radicalised yet not committing related crimes.

The problem has become more dramatic in recent years, due to the expanding number of suspects.

This is made more difficult as the shift from words to actions - carrying out an attack - is often sudden and unpredictable.

Terror attacks have increasingly involved unsophisticated weapons and attack plans, for example those involving knives and lorries.

These lack the extensive planning that characterised most terrorist attacks in previous years and are more difficult to spot as a result.

Countries have tried to partially overcome this challenge in various ways.

Italy, for instance, carries out administrative deportations of known radicals who do not possess Italian citizenship: some 350 people in the last three years. However, this does not deal with the problem that most terror attacks in Europe are carried out by citizens.

The UK uses court-mandated Terrorism Prevention and Investigation Measures (TPims) to limit the movements and the communications of known radicals.

Prosecutors in other countries have resorted to arresting some radicalised individuals for non-terrorism related crimes, such as tax evasion and violation of gun laws.

These approaches mitigate the problem, but ultimately do not solve it: there are limits to how much a democracy can do to fight terrorism.

It is not uncommon to hear calls to imprison "all radicals" when a terrorist attack is carried out by someone already known to hold extremist views.

But while it is possible that legal systems can be adapted to pursue potential terrorists, there are some red lines a democracy will not cross.

About this piece

This analysis piece was commissioned by the BBC from an expert working for an outside organisation.

Dr Lorenzo Vidino, external is the director of the Program on Extremism at the George Washington University, external.

Edited by Duncan Walker