How Tunisia is keeping Arab Spring ideals alive

- Published

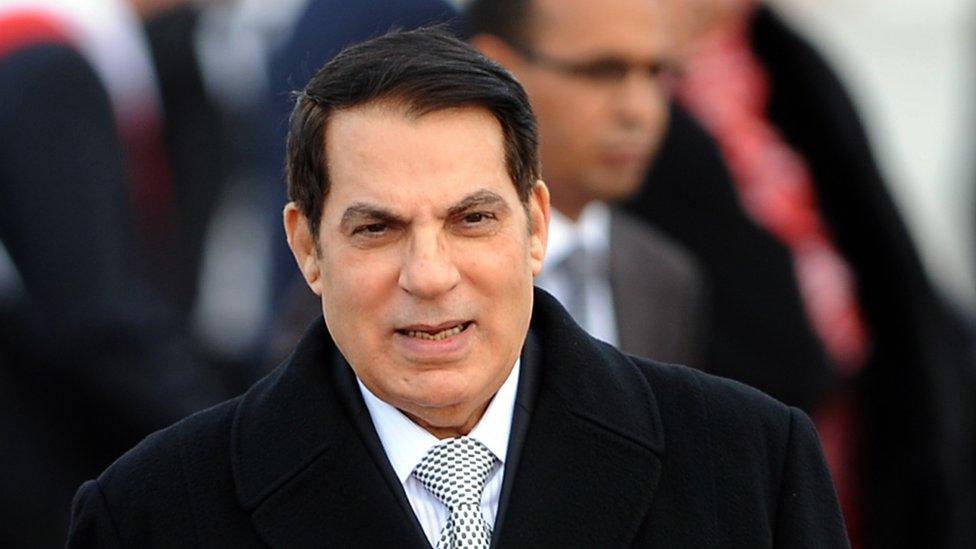

Tunisia's uprising was the first and most successful of the Arab Spring

A group of civil society organisations in Tunisia has been awarded the 2015 Nobel Peace Prize. How has the country managed its transition to democracy where so many others have failed?

Iraq and Syria are trapped in intractable civil wars. Egypt is run by its army. Libya has all but disintegrated.

But in the midst of all the Middle Eastern chaos, Tunisia has somehow kept its democratic development on track. Since the overthrow of President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali in 2011 the country has held two competitive and peaceful general elections.

Strong forces oppose Tunisian democracy. In March this year jihadists killed 22 people in Tunisia's National Museum. Three months later 38 were murdered in the Sousse beach massacre.

But while the jihadist challenge has been both deadly and spectacular, those using violence have enjoyed little popular support.

Arguably, a greater threat to political reform has come from the divisions between three powerful elements of Tunisian society:

the political (and non-violent) Islamists

the diehard secularists

the old regime elements

All three groups have had good reason to fear each other.

Zine El Abidine Ben Ali served as President for more than two decades before being ousted in 2011

Mutual mistrust

In the post-Ben Ali period the Islamists in Ennahda, Tunisia's version of the Muslim Brotherhood, had genuine anxieties about being thrown back into the prisons from which thousands of their activists emerged during the Arab Spring.

For their part, the secularists feared that, whatever the Islamists said in public, secretly they wanted to create an Islamic state in which European lifestyles would become impossible.

Meanwhile, the elite families who benefited from decades of cronyism in the Ben Ali era, worried about being held accountable for their ill-gotten gains.

Some Tunisians have accused the old elite of wanting to defend their economic interests by restoring paternalistic, authoritarian rule. Anti-terror legislation, for example, has been used to close down civil liberties.

And yet, somehow, despite all the problems and obstacles, Tunisia has remained in the vanguard of democratic development in the Middle East.

Peace Prize

The Nobel Committee has given the credit to the National Dialogue Quartet. Drawn from four civil society groups - unions, lawyers, employers and human rights activists - it became active at a crucial moment in 2013 when the assassination of two prominent, left-wing politicians threatened to spill over into a broad civil conflict.

The murders were taken as a sign that the Islamists in the country would stop at nothing to achieve political dominance. The anti-Islamist opposition walked out of the constitutional assembly.

It was at this point that the Quartet set about the business of solving Tunisians' differences through politics not violence.

Tunisia's National Dialogue Quartet

The surprise winner of this year's Nobel Peace Prize has played a key role in mediating between the different parties in the country's post-Arab Spring government.

The Quartet is credited with creating a national dialogue between the country's Islamist and secular coalition parties amid deepening political and economic crisis in 2013.

Tunisia's revolution - also known as the Jasmine Revolution - began in late 2010 and led to the ousting of President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali in January 2011, followed by the country's first free democratic elections.

Kaci Kullman Five, the chair of the Nobel peace committee, said the Quartet's role in Tunisia's democratisation was "directly comparable to the peace conferences mentioned by Alfred Nobel in his will".

New constitution

The mediators only succeeded because of the commitment of other Tunisians to pluralism and the democratic process.

Unlike its counterpart in Egypt, for example, the Tunisian army has never had political ambitions.

And during the political crisis of 2013, the Islamists, disproving all their critics' predictions, set aside their election victory. After protracted negotiations managed by the Quartet, Ennahda gave up power so as to achieve a broader political settlement.

Tunisia's transitional period culminated in 2014 with agreement on a new constitution and the election of a coalition government that included all the major political forces in the country.

Mohamed Bouazizi set himself on fire after police confiscated the fruit and vegetables he was selling without a permit; his actions were seen as a catalyst for the Arab Spring in Tunisia

Challenges ahead

The Arab Spring began in Tunisia when a street vendor, Mohamed Bouazizi, became so angry at being unable to make even a modest living that he set himself alight.

Many in Tunisia's relatively well-educated population remain deeply frustrated that they cannot fulfil their potential and provide for their families.

Tunisia's Islamist and secular politicians are both learning that, for many in the electorate, the question of what role religion should play in politics is a second order concern.

For most voters the most pressing issues are the poor provision of basic government services, the uncertain security situation and, most crucially of all, the lack of jobs.

The economic and political challenges ahead are real. But for the moment Tunisians can look back at the last four years - and at their Quartet's Nobel Prize - and celebrate the fact that, so far, compared to everyone else in the region, they have managed to keep the ideals of the Arab Spring alive.

- Published9 October 2015

- Published9 October 2015

- Published2 December 2014

- Published19 November 2014

- Published9 October 2024

- Published5 March 2015