Emmerson Mnangagwa: Will he be different from Mugabe?

- Published

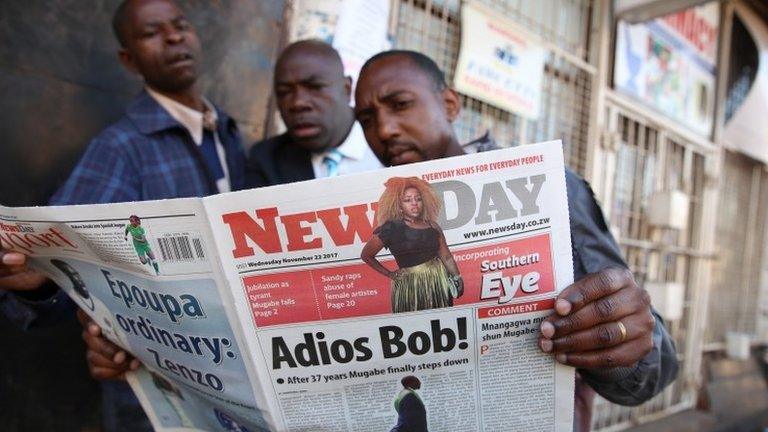

"This is the beginning of a new unfolding democracy in our country," Emmerson Mnangagwa told his supporters at his first public address since returning to Zimbabwe. But is it?

For five decades, Mr Mnangagwa was former Zimbabwean President Robert Mugabe's protégé, comrade, and right-hand man.

He was at his side during the fight against white minority rule, and during the post-liberation government.

He is also said to have been behind some of the most notorious acts of repression which helped keep Mr Mugabe in power.

There are, however, some key differences between the man likely to become Zimbabwe's new president, and his former mentor.

Here are a few of them:

Youth on his side - relatively

Young people were among the thousands waiting to welcome Mr Mnangagwa

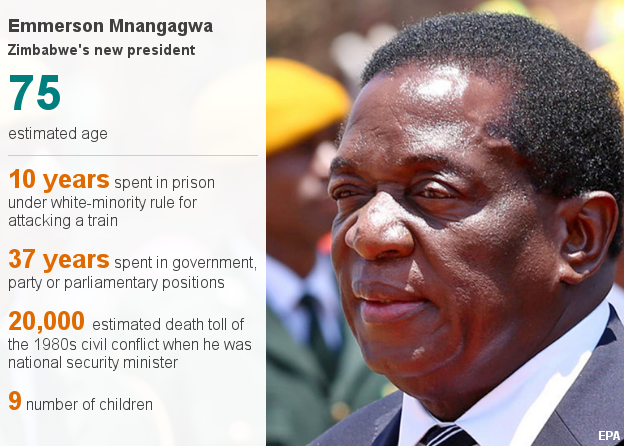

Mr Mnangagwa may be in his 70s but that is still around two decades younger than the man he is replacing.

There is some dispute over whether he is 71 or 75. Mr Mnangagwa is said to have avoided being hanged when arrested during the fight for independence by lying about his age.

But while Mr Mugabe was notoriously stubborn, Mr Mnangagwa is said to be more flexible in his approach, if only for the purposes of achieving his goals.

With elections planned for next year, many in the ruling Zanu-PF party, whose ranks are filled with veterans of the struggle for independence, will be hoping he can reach out to Zimbabwe's youth.

Mr Mnangagwa (right) fell in and out of his former leader's graces

However, like Mr Mugabe, he has a reputation for ruthlessness. He was in charge of state security during the Matabeleland massacres of the 1980s, in which some 20,000 people were killed on suspicion of being part of a rebellion.

And human rights groups accuse him of being behind a violent crackdown on opposition supporters after the disputed 2008 election.

So one key question facing Zimbabwe, is whether he will allow the next election to be free and fair.

Pragmatic

Emmerson Mnangagwa received a hero's welcome on his return

As well as being more flexible, Mr Mnangagwa is arguably more pragmatic than Mr Mugabe.

He is said to have recently held secret talks with opposition leader Morgan Tsvangirai, although the BBC has not been able to independently verify this.

While it is still far from certain that he would be open to a widely mooted government of national unity, it certainly looks more likely than it did a week ago.

For Mr Mnangagwa, a key concern - by most accounts - is showing the international community that his country is stable, in order to secure investment in the economy.

Open for business

The BBC's Stanley Kwenda in Harare says that Mr Mnangagwa has a good reputation in the business sector, and tried to protect productive farms operated by white farmers during the controversial land reform programme.

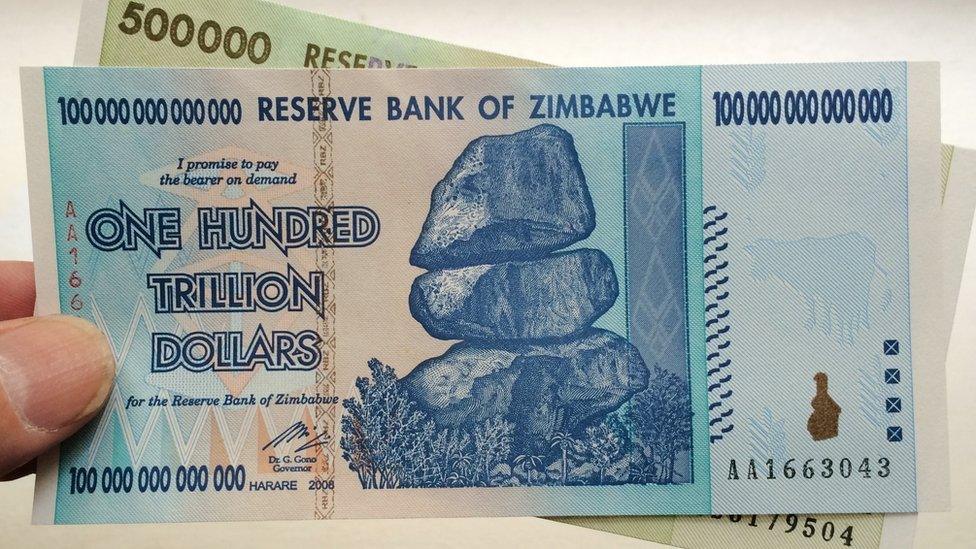

Mr Mnangagwa served as acting finance minster between 1995-1996, during a period of relative economic stability.

He said in an interview last year that "capital goes where it feels comfortable and warm, and if it's cold it runs to a country which gives it better weather".

That seems to have been a reference to the dire state of Zimbabwe's economy, and what it might take to turn it around following years of sanctions imposed after the seizure of white-owned farms.

And in his speech after his return from exile, he said his focus would be on "jobs, jobs, jobs".

Who is Emmerson Mnangagwa?

Called "the crocodile" because of his political shrewdness - his Zanu-PF faction was known as "Lacoste"

Received military training in China and Egypt

Tortured by Rhodesian forces after his "crocodile gang" staged attacks

Helped direct Zimbabwe's 1970s war of independence

Became the country's spymaster during the 1980s civil conflict, in which thousands were killed

Denies any role in the massacres

Seen as key link between army, intelligence agencies and Zanu-PF

Accused of masterminding attacks on opposition supporters after 2008 election

Journalist Martin Fletcher, who interviewed him last year, says Mr Mnangagwa was keen to indicate that Zimbabwe would change under his leadership.

Mr Fletcher told the BBC that "he wanted to signal to the West that he would be different from Mugabe, that he understood the need to restore the Zimbabwean economy. He was saying 'we want to attract foreign investment, [and] he talked about the need for the diaspora to come back, about the need to re-engage the West'".

That is likely to mean getting rid of polices like the indigenisation laws, which required all companies - including foreign investors - to be 51% owned by indigenous, ie black Zimbabweans.

He is also likely to address the issue of land ownership, and access to land for white farmers.

Army links

Zimbabwe Army General Constantino Chiwenga (left) is an ally of Mr Mnangagwa

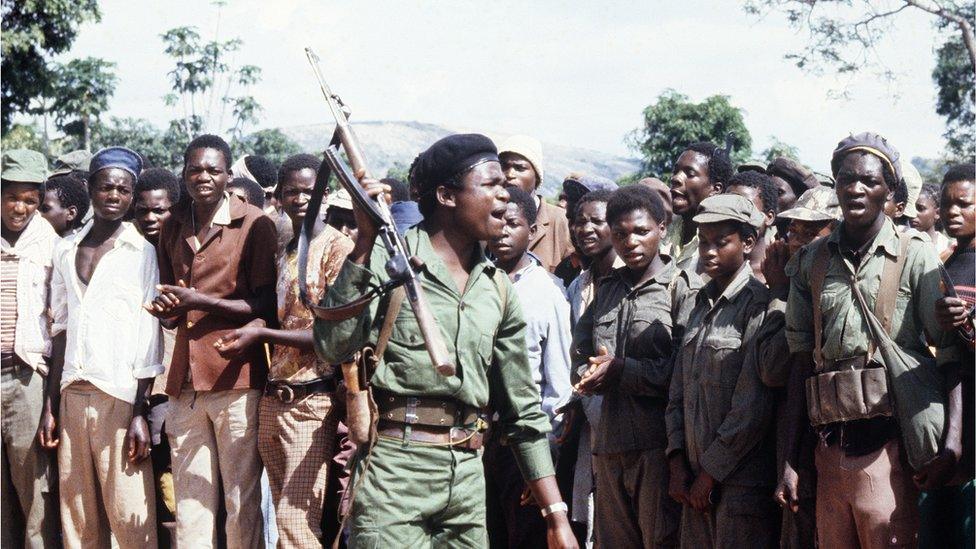

Mr Mugabe always enjoyed the support of the army, having been the political leader of the 1970s war of independence in which most of Zimbabwe's generals fought.

But he was ultimately toppled by the military, who were even more loyal to Mr Mnangagwa.

In particular, Mr Mnangagwa is close to army chief Gen Constantino Chiwenga.

Chiwenga: The army chief who took power from Mugabe

On his return to Harare following Mr Mugabe's resignation, Mr Mnangagwa said that he had been "in constant contact" with security chiefs during the military takeover.

Mr Mnangagwa was a teenage fighter in the war of independence, which he went on to lead.

Those who fought in Zimbabwe's 1970s war of independence have long monopolised power

As national security minister during the 1980s, he cemented his ties in the military and intelligence services, which have remained a loyal base.

It is perhaps this relationship that concerns the opposition the most.

MDC-T MP Eddie Cross told the BBC that "in many respects he is one of the architects of the collapse in Zimbabwe".

"He's certainly been involved in many of the not-so-good episodes in recent years, including the 2013 election, which he pretty much managed on his own.

"I think, for many of us, we will fear that there won't be sufficient change".

Charisma deficit

Mr Mnangagwa's supporters within Zanu-PF are known as the Lacoste faction

Whatever his faults, Mr Mugabe was undoubtedly a powerful orator, at ease whipping up a crowd, or, in the early days at least, discussing delicate diplomatic issues with world leaders.

The same cannot be said of Mr Mnangagwa.

His daughter says he is not an emotional man, while his son (a Harare DJ known as St Emmo) says: "He doesn't say much and I think that's what frightens people - like: 'What is he thinking?'"

His nickname is "The Crocodile", hardly one of nature's most charismatic beasts.

It was originally given to him during the liberation struggle when he led the so-called "crocodile gang".

The name was later used to refer to his political shrewdness - his ability to lie low and then attack, viciously.

- Published3 August 2018

- Published21 November 2017

- Published21 November 2017

- Published22 November 2017

- Published22 November 2017

- Published22 November 2017

- Published25 July 2018