Zimbabwe after Mugabe: What happens next?

- Published

"The president has arrived… the president has arrived."

As president-designate Emmerson Mnangagwa's motorcade whizzed past on the street below, the voice of an unidentified man blurted out in mobile phone footage posted on social media.

On Friday, Mr Mnangagwa will be sworn in as interim president following President Robert Mugabe's shock resignation.

Mr Mnangagwa was swarmed by party supporters after he emerged from hiding on Wednesday.

It was the running commentary from the crowds that caught my attention.

"Just look at the size of the motorcade," a woman marvelled as military police, regular police, luxury cars and SUVs streamed past. A military helicopter hovered above.

"Why is it so large?" another asked.

The size of his predecessor Mugabe's motorcade was also a talking point for locals - half a dozen motorbikes, an ambulance, two truckloads of soldiers and about a dozen other mainly luxury vehicles.

As Mr Mnangagwa sped through town, already the comparisons have started.

Views from Harare: ‘We need fairness not corruption’

Zimbabweans are looking for a break from the past.

When the army tanks rolled into Harare on 14 November, Zimbabweans were stunned. The military had always been associated with keeping President Mugabe in office, but not any more.

It has long been said that people get the leader they deserve - that Zimbabweans had Mr Mugabe in power because the majority had stopped bothering to vote.

But a Zimbabwean watching events unfold in another country told me: "The fact that it has taken the military to force his hands shows what we have been up against all these years."

She said that for so long Zimbabweans had tried to remove him and played by the rules but failed.

She is right. In 1990, founding Zanu member Edgar Tekere tried to contest the presidency for the Zimbabwe Unity Movement party. His party supporters were attacked and some reportedly murdered.

More on Zimbabwe after Mugabe

When Morgan Tsvangirai of the Movement for Democratic Change won the first round of the presidential vote in 2008 there were violent reprisals, and he pulled out of the second round.

Zimbabweans resigned themselves to the fact that any change in presidency would come from within.

They never imagined the rules would have to be broken.

Last Saturday, more than 100,000 Zimbabweans took to the streets to "show support for the war veterans and the military" and to call for President Mugabe to step down. They feted soldiers and tanks. Posters referring to the commander of the military who led the takeover read: "Chiwenga, the people's general."

Leader of Zimbabwe's opposition MDC party, Morgan Tsvangirai, warns about a "power retention agenda"

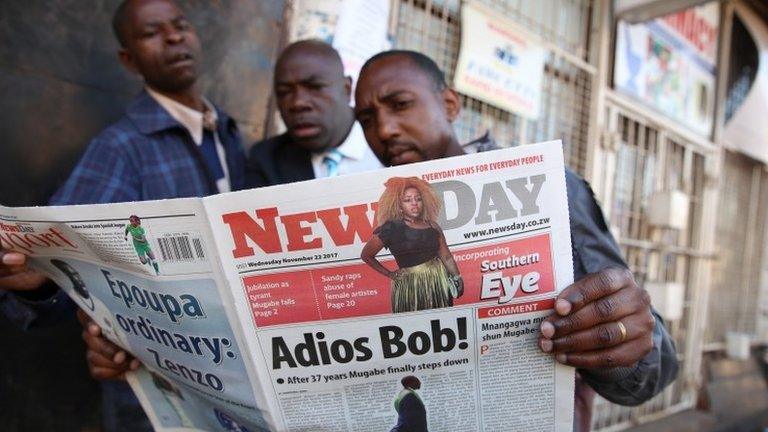

Following President Mugabe's resignation on Tuesday, the crowds dancing in the street spoke of people power, of their newfound ability to use power to bring change. A young man said: "Mnangagwa must learn a lesson. We have found out our voice and will not allow him to do what Mugabe did to us."

Those celebrating were the lucky ones - lucky to have lived beyond the Mugabe era.

Thousands of others didn't have a chance: those buried in the unmarked graves and mineshafts of Matabeleland and elsewhere who were brutalised for opposing Robert Mugabe. The thousands, including children, who never got the chance at life. Those who died in badly funded state hospitals as Mr Mugabe flew to Singapore on public funds to extend his own life.

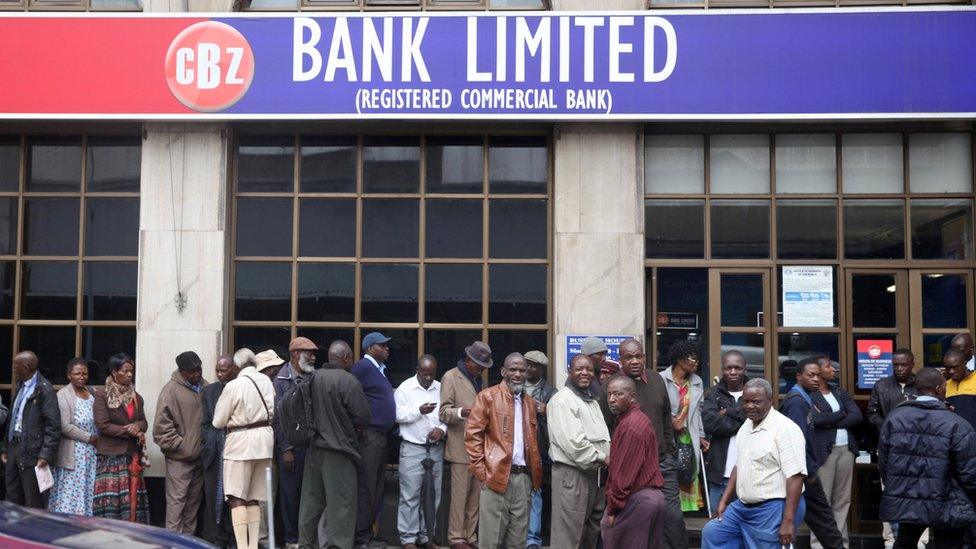

For so many years, Zimbabweans have felt an unspoken shame as their economy crashed and millions of members of one of Africa's most literate workforces - young and old - fled the country for menial jobs in foreign lands.

Zimbabwe's week of upheaval in two minutes

President Mugabe often said independence in 1980 came by the gun and not by the vote. The words are self-fulfilling. His own exit has come, not by a vote, but by the gun.

But now that he has gone, will we see a new era?

Zimbabwean commentator Brian Kagoro described the events of the past few days as a "Zanu PF factional fight" for power "dressed up as a people's revolution".

It is ironic that Emmerson Mnangagwa, one of the symbols of Zanu PF repression, is now seen as the face of hope.

Who is Emmerson Mnangagwa?

Known as "the crocodile" because of his political shrewdness - his Zanu-PF faction is "Lacoste"

Received military training in China and Egypt

Tortured by Rhodesian forces after his "crocodile gang" staged attacks

Helped direct Zimbabwe's war of independence in the 1960s and 1970s

Became the country's spymaster during the 1980s civil conflict, in which thousands of civilians were killed, but has denied any role in the massacres, blaming the army

Accused of masterminding attacks on opposition supporters after 2008 election

Says he will deliver jobs, and seen as open to economic reforms

Zanu PF still needs to redeem its image in southern Zimbabwe, where atrocities were carried out. But Zimbabweans forgave atrocities committed by the former white minority government led by Ian Smith, who once said: "The more we killed the happier we were".

He was behind the deaths of 30,000 black Zimbabweans but lived on his farm in peace in post-independence Zimbabwe.

No-one knows what lies ahead under an Emmerson Mnangagwa leadership. He will have to temper expectations for a quick turn-around, with jobs and more jobs. He is a lawyer, and for some a pragmatic pro-business leader who listens but rarely speaks.

This week, I have seen a hope in Zimbabweans' eyes, something I have not seen in many years.

It's not clear whether Mnangagwa can bring that change - politicians rarely change of course. What is different in Zimbabwe today is that ordinary people are coming round to the realisation that they have the power to push back and to be that change.

The singing and celebration spring from the belief that the worst is over.

For the past few days I have seen a pride that has long been absent.

This is where a new era can spring from.

- Published23 November 2017

- Published22 November 2017

- Published22 November 2017

- Published22 November 2017

- Published22 November 2017

- Published21 November 2017

- Published21 November 2017