Mamoudou Gassama: Travelling is a rite of passage for many Malians

- Published

Mamoudou Gassama comes from an ethnic group which is famous for travelling

Mamoudou Gassama's four-storey dash to save a small boy in France is a reminder of another Malian hero who gained international prominence for a brave rescue.

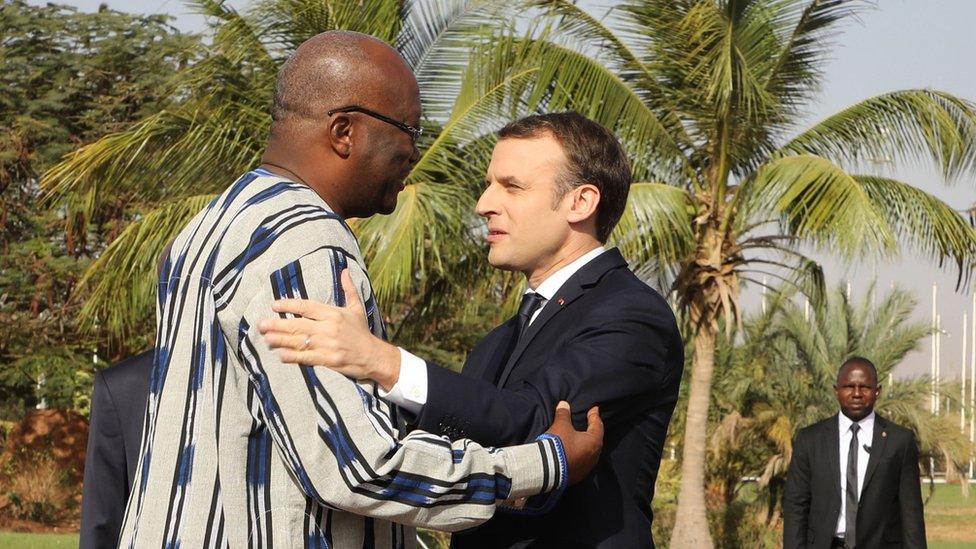

In January 2015, Lassana Bathily was credited with saving the lives of six hostages including a baby during an extremist attack on a Jewish supermarket in Paris. He led them to a safe hiding place, escaped, then directed gendarmes to them.

Two weeks later - after six years of struggling to secure legal residency in France - Mr Bathily was given a medal and a French passport by then President François Hollande.

In 2016, he wrote a book ''Je ne suis pas un heros'' (I am no hero) and created a charity whose first project was to provide irrigation for his home village in western Mali.

'Humanity and love'

Like Mr Bathily's selfless leadership to save the hostages, Mr Gassama's heroic climb to save the boy cements the image of Mali as a country with a culture of old-fashioned public spiritedness.

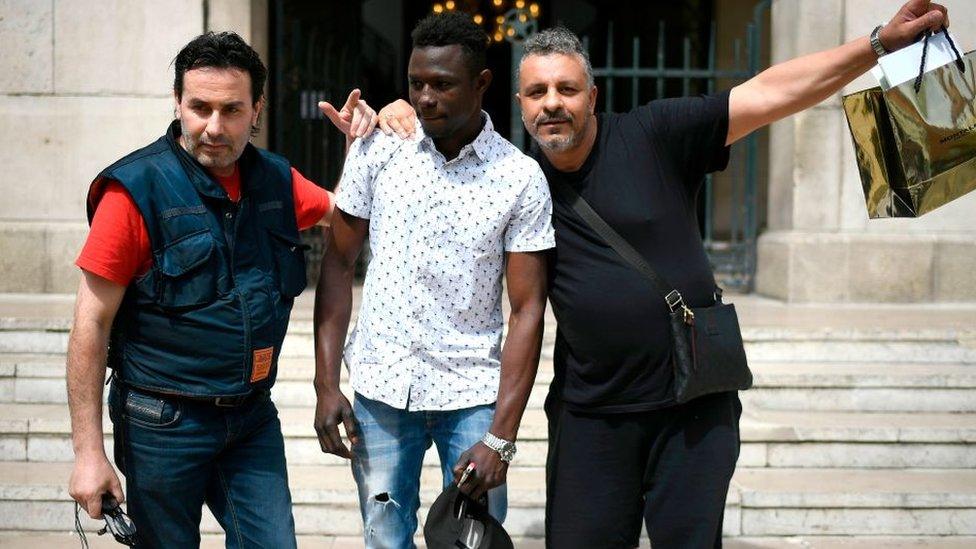

Malian "Spiderman" rescues Paris child - then meets French president

Following Mr Gassama's meeting with French President Emmanuel Macron, Mali's ambassador in France, Toumani Djimé Diallo, said: ''The courage of our young compatriot aged 22, an undocumented migrant, shows that his values are of humanity and love for his neighbour.

"These are fundamental values in Malian society and are Republican values shared by France.''

Lassana Bathily was given French citizenship for his bravery

Mr Gassama, who is understood to have been in France for only six months, is among thousands of Malians still making the journey to Europe, despite much-publicised measures to limit immigration to the continent.

This is not only because of the failure, so far, of European Union attempts to stop people from crossing the Sahara and Mediterranean.

It is also because many of those of who leave Mali - including Mr Gassama, as his surname indicates - are from the Soninke ethnic group.

Large-scale expulsions

For Soninko (the plural of Soninke), travelling has for centuries been an obligatory rite of passage to manhood.

So well established is the Malian travelling tradition - and so strong are the emigrants' links with home - that when Mali's population is stated to be 12 million, the figure includes a diaspora estimated at about three million people.

The Ministry for Overseas Malians says that remittances from the diaspora - estimated at more than $3bn (£2.25bn) per year - easily provide a third of the country's GDP.

But it is important to keep perspective on African emigration. Most sub-Saharan Africans who travel to seek work do so within the African continent - and because of Mali's strong emigration tradition, its statistics are a useful indicator of the broader picture.

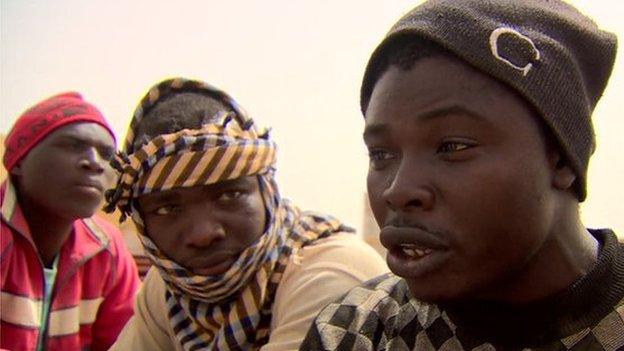

Many Africans risk their lives to reach Europe

Data collected by the ministry shows that of 89,134 Malians repatriated by force or voluntarily between 2002 and 2013, more than 90% (81,755) were sent back by other African countries - in particular, Ivory Coast, Libya, Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia.

As a matter of comparison, in the same period, European countries expelled 5,947 Malians.

More recently, there have been large-scale expulsions of Malians from the Central African Republic, Angola and Gabon.

Storming fences

Many African countries have well-established Malian - chiefly Soninke - communities which are engaged in trade.

As a consequence, a Malian who travels - be it to Nouakchott or New York - has friends and solidarity wherever he or she goes.

For the Malians who do travel to Europe there are two options. Those who have a relative in the EU - most often in France or Spain - might seek an invitation and a tourist visa, secured legally but on which they might decide to overstay. For them, the preferred means of travel is by air.

For the past 30 years, migrants from sub-Saharan Africa without passports or visas have used four main routes to cross by boat to Europe.

The busiest, until 2012, was to the Canary Islands which belong to Spain. But this exit point was blocked after Spain's Gardia Civil, or law enforcement agency, was stationed in Mauritania. They are still there.

Many people migrate because of political instability or poverty

Ceuta and Melilla are two Spanish enclaves on the northern Mediterranean shore of Morocco. In recent years, there have been occasional, spectacular storming by migrants of the fences around the enclaves. Moroccan co-operation with the EU has largely closed this route.

Malta and southern Italy (Lampedusa) are reached by boat from Algeria and Tunisia.

But this route is less in favour at the moment as it requires travelling through Algeria - which has sent back 27,000 migrants since 2015 and is regularly criticised by human rights groups for treating them in a degrading way.

Also, Algeria is reached after a six-day truck journey through the desert of northern Mali, where landmines and other explosive devices are a threat.

Empire crushed

The favoured route across the desert has moved eastwards. As a result of anti-migration moves by the EU in Mauritania and Morocco, the insecurity in northern Mali and the instability in Libya, the favoured exit point from the south into the desert is now Niger.

This is where the EU is currently concentrating its efforts to reduce emigration.

About 7,000 African travellers were made to turn back in Niger last year, up from 1,400 in 2014. More than 2,000 returns in the first three months of 2018 suggest another record year.

European policymakers argue that the best way to reduce immigration pressure from Africa is for rich countries to help create economic opportunities in countries like Mali for the continent's young population.

This is partly true. But Soninke men - like the 22-year-old Mr Gassama - will continue to travel.

It has been like that ever since the Ouagadou Empire, which was built on the wealth from gold and salt exports, was crushed by Soundiata Keita's Mali Empire 700 years ago.

When things got tough for the Soninkes, fathers began to encourage their sons to travel away in the lean season, instructing them to return only once they had enough money to get married and establish a family.

So the EU will not find it easy to reverse a tradition that dates back to the year 1240 or thereabouts.

Knowing that Soninkes will always be on the move, the best option would be for other, emerging African countries - perhaps with the help of European investment - to speed up their development and accommodate energetic and fearless Malians like Mr Gassama.

More about migration:

- Published28 May 2018

- Published28 November 2017

- Published21 April 2015

- Published30 December 2016

- Published28 July 2023