Letter from Africa: Why journalists in Nigeria feel under attack

- Published

Former cabinet minister Femi Fani-Kayode launched into a tirade against a journalist on live television

In our series of letter from African journalists, Mannir Dan Ali, former editor-in-chief of Nigeria's Daily Trust newspaper, looks at difficulties Nigerian journalists face for simply doing their job.

In Nigeria questions are still being asked about why some public officials consider journalists to be their errand boys.

This follows the outrage that greeted a tongue-lashing one reporter received from a former government minister and member of the opposition People's Democratic Party (PDP).

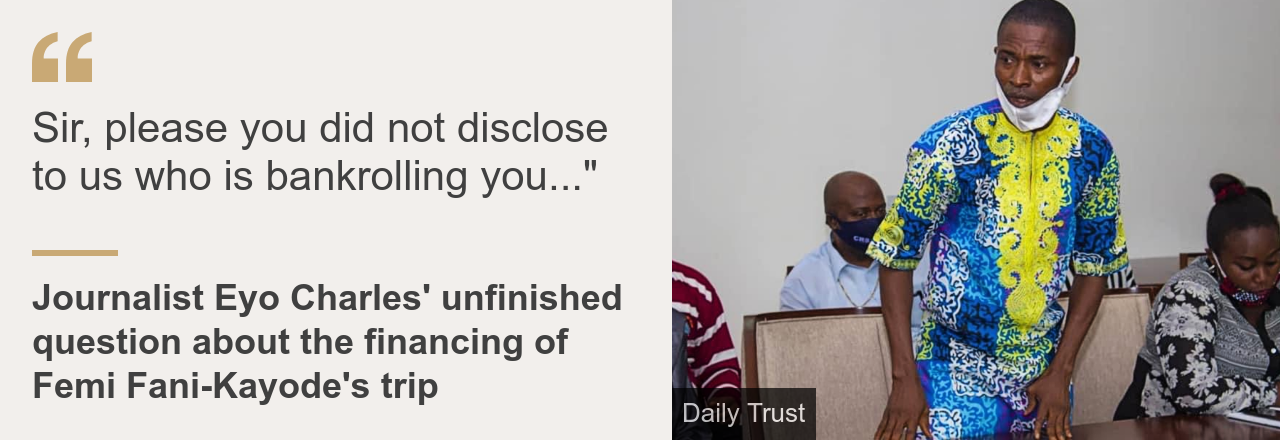

It was all caught on video when Femi Fani-Kayode did not like a question he was asked by journalist Eyo Charles.

Mr Fani-Kayode, who holds no official position within the government or the PDP, has been publicly inspecting state government projects around the country.

After each inspection, he has called a press conference to give the project a thumbs up.

It was in Calabar, the capital of Cross River, the third state he had visited in recent months, that Mr Fani-Kayode lost his cool, external when Charles asked him about the financing of his trips: "Sir, please you did not disclose to us who is bankrolling you…"

Instead of even allowing the journalist to finish his question, a fuming Mr Fani-Kayode called him "very stupid" and alleged that he looked like a poor man who collected bribes, known here as "brown envelopes", from newsmakers.

This apparently was one of Mr Fani-Kayode's least insulting run-ins with a journalist.

I too have had an encounter with him, when he was in government serving in the cabinet of then-President Olusegun Obasanjo more than a decade ago.

It went beyond an insult. It took place at the presidential villa, known as Aso Rock, where he threatened to slap me, prompting other journalists to come between us.

I had no idea at the time why he was angry; it was only later I understood it was to do with controversial comments he had made in a live interview he had given to the BBC about Mr Obasanjo's third term ambitions, external.

The interview became hot news and he took his anger out on me as the BBC reporter on the ground at the time.

Horsewhip threat

It is not only Mr Fani-Kayode who perceives journalists as irritants.

Some months back, the governor of south-eastern Ebonyi state banished two journalists from practising there over what he said was their penchant for writing negative reports about the state.

"If you think you have the pen, we have the koboko," the governor warned using a local word for a horsewhip.

Media reaction, external to the governor's order led to a reversal of the banishment.

You may also be interested in:

Debunking fake news in Nigeria

Several years ago at the Daily Trust, we had to pull out a reporter from a state after some thugs beat him up at a public event after the state governor took exception to his reports.

In its comment on the recent Fani-Kayode incident, Amnesty International condemned the manner in which the journalist was treated.

"Journalists seek accountability on behalf of the people and should not be threatened or abused for asking questions," the human rights body's statement said, external.

The public outcry has now forced Mr Fani-Kayode to apologise to the journalist, external - though he is still threatening to take the Daily Trust newspaper and one of its columnists to court over the matter.

Clearly this is not the last to be heard on the uneasy relationship between the media and Nigeria's newsmakers.

Aside from threats and verbal attacks, there are also subtle ways in which the media in Nigeria, and I dare say in many other African countries, is hobbled.

Some government organisations and big companies deny advertising to outlets they consider have given them unfavourable coverage.

Then there is the poor remuneration or even outright non-payment of salaries by some media houses, which means that some journalists have allegiances to those who can pay.

Some actively seek cash handouts before they cover events or do stories.

Beggars' palace

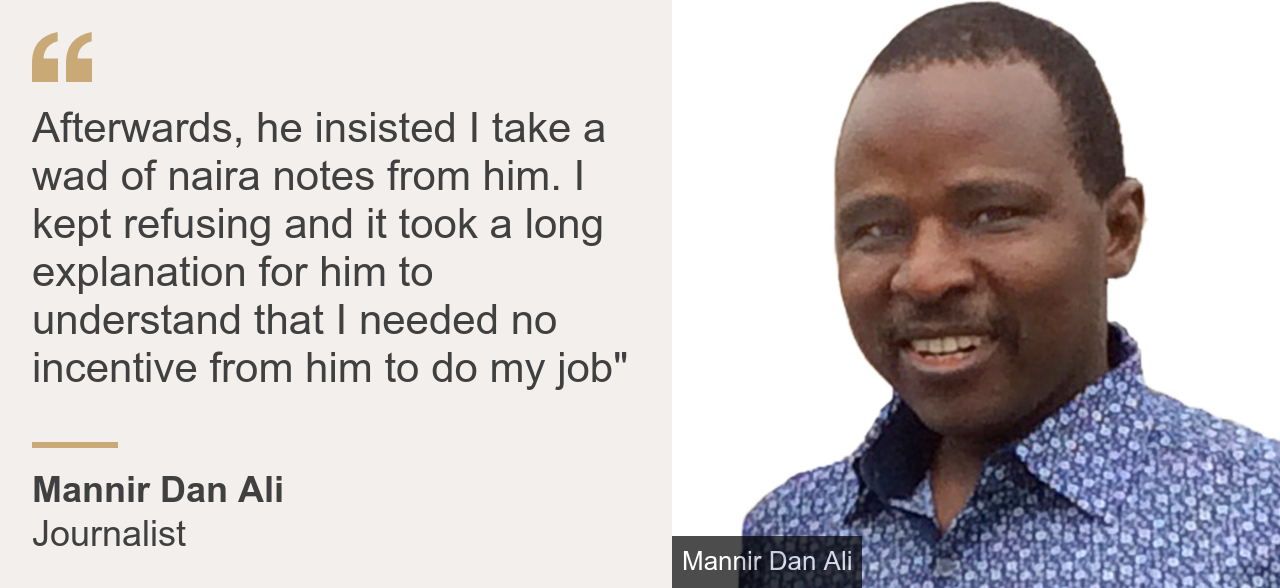

From my experience as a journalist in Nigeria, it is not only the rich and powerful who assume journalists are on the take.

One vivid instance involved the head of a group of beggars at a big rubbish dump in Ijora Badia, a slum in Lagos.

I had gone to interview him for the BBC in the late 1990s to find out what he made of an attempt by the authorities to get beggars off the streets and into a rehabilitation centre.

He was holding court at what he called his palace, built right at the top of the tip from discarded wood, where he scoffed at the proposal.

Afterwards, he insisted I take a wad of naira notes from him.

Some journalists expect to be paid for covering events by the organisers

I kept refusing and it took a long explanation for him to understand that I needed no incentive from him to do my job.

More recently at a US embassy event to mark Press Freedom day in Abuja, a young reporter wanted to know why it was not right to take to money for covering events.

He felt it was like paying those who make presentations at workshops and other functions.

One of the speakers at the event explained delicately with a proverb, saying "the hand of the giver is always at the bottom of the hand of the taker" - implying that when a journalist takes such offerings, he or she is unlikely to be objective or ask the difficult questions.

Sadly in Nigeria at those rare moments when uncomfortable questions do get asked, a journalist can get the Fani-Kayode treatment.

More Letters from Africa:

Follow us on Twitter @BBCAfrica, external, on Facebook at BBC Africa, external or on Instagram at bbcafrica, external

- Published28 July 2023