India's awakening youth threaten political status quo

- Published

Young Indians have taken to the streets over a number of issues challenging India's political class

Many observers expect Indian voters to punish the ruling Congress party in this spring's general election for the country's sharp economic slowdown and a string of corruption scandals. But the poll may become a referendum on all established politicians amid a groundswell of anger at their failings. Andrew North, the BBC's South Asia correspondent, reports that an increasingly engaged younger generation is leading the charge.

The police had sealed off Delhi's government district, even closing metro stations to try to keep demonstrators away.

It was December 2012 and for Anshul and his friends it meant a four-hour round trip each day to join the protests over the fatal gang rape of a Delhi student.

"There were lots of police trying to stop us," the 23-year-old student remembers, "but we had to be there."

Thousands of other young people joined similar protests across the country, shaking the Congress-led government and turning the Delhi gang rape into a darkly defining moment of India's recent history.

It also marked another moment in what many see as a growing nationwide awakening among young Indians, increasingly despairing of the way their country is being run.

One year after the rape protests, Anshul and his friends showed their power again in Delhi's local elections, joining with thousands of other young people in voting for Arvind Kejriwal, a maverick former tax inspector turned anti-corruption campaigner.

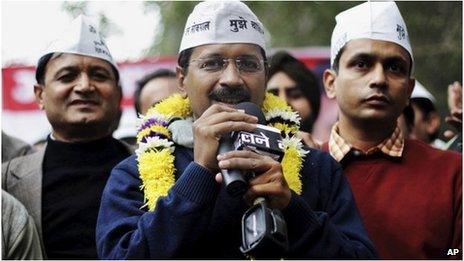

Arvind Kejriwal has promised to put an end to corruption in Delhi

Just a year after creating his Aam Admi (Common Man) party, Mr Kejriwal had claimed the scalp of Congress, India's oldest party, ending its 15-year control of the city.

It was also an upset too for Congress's main rival, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), denying it an outright majority.

All parties tainted

Congress, which has led India for most of its years since independence under the control of the Nehru-Gandhi dynasty, is the chief target of this growing anger.

The party, at the helm of the ruling coalition over the past decade, has presided over an alphabet soup of corruption scandals, involving everything from the 2010 Commonwealth Games to mobile phone networks and coal.

In the meantime, India's economy has gone from boom to near-bust.

But the whole political class has become tainted.

A third of India's elected lawmakers are accused criminals, a figure that has risen with each election.

For many voters, Mr Kejriwal's AAP looks like a genuine new alternative.

"People are sick of the corruption and ineptitude of all the established parties," says Vishal Dadlani, a well-known musician who has won new fame and flak for publicly backing the AAP.

Even Mr Kejriwal's critics, such as author and former Procter & Gamble India chief executive Gurchuran Das, credit Mr Kejriwal with giving Indians "a new sense of nationhood".

Nearly 150 million Indians will be eligible to cast ballots for the first time in these polls - more than a fifth of the electorate - and in marginal constituencies their decisions could be crucial.

Youth turnout has been rising at each election, according to Prof Sanjay Kumar. of the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies.

And in the Delhi state elections last year, nearly half of voters aged 18-25 backed the AAP.

"I wouldn't have voted for anyone else if it didn't exist," says Anshul.

That has concentrated minds in the big parties, and they are taking the youth vote much more seriously - especially as the AAP hopes to contest at least two-thirds of the seats in the general election.

'Illiberal protest movement'

In a recent television interview, the Congress campaign leader Rahul Gandhi peppered his answers with references to "empowering" India's "young" and "women", regardless of the questions.

Likewise, the opposition BJP has been trying to recruit more young people to act as ambassadors for its campaign.

But some of the shine has come off Mr Kejriwal's "anti-politician" appeal now that he has joined the political class.

Since becoming Delhi's chief minister, he has been attacked for using the job as a protest platform, instead of governing the city region.

His defenders say that is unfair. But a sit-down protest, blocking central Delhi and aimed at winning control of the city's police, dismayed many of his middle-class backers.

It has shown the AAP is "basically an illiberal protest movement", says Mr Das, predicting it "will go into the dustbin of history".

He adds: "Aspiring India deserves better."

Congress campaign leader Rahul Gandhi is hoping to appeal to disillusioned voters

Some young Indians have lost hope in political change altogether.

"I'm thinking of going abroad - and my friends too," says Aditi, a media student in the southern city of Bangalore. "India is just too restrictive."

Despite the AAP's success in channelling discontent with India's political class, it will be hard for it to make a national breakthrough. Its base is mainly urban, but most Indians - including the young - live in rural areas, where older parties are better organised.

Mr Kejriwal's support is scattered and current predictions suggest he may win only 10 of 545 national parliamentary seats.

None of the above

And at these elections, Indians will have the chance to register a protest vote against all their politicians - including Mr Kejriwal. For the first time, they will be able to vote "none of the above" on their ballot papers, which could take away significant support.

Aarti, another veteran of the Delhi gang rape protest, admits she has had second thoughts about Mr Kejriwal since voting for him last year.

"He was the lesser evil," she says. "But I may vote 'none of the above' next time."

With jobs the biggest issue for millions of young Indians, many may vote with their head rather than their heart: for Narendra Modi, the leader of the BJP.

Returning India to robust economic growth is at the heart of his campaign. He is still the front-runner to be the next prime minister, despite lingering questions over his handling of deadly communal riots in 2002 in his state of Gujarat.

The so-called 'Kerjiwal effect' has seen Indian politicians cut back on their bloated motorcades

By contrast, the AAP would be a disaster if it won real power, says Mr Das, because of what he calls its "socialist, anti-reform" economic policies.

Yet many are still prepared to give the evolving AAP a chance. The party has claimed to be signing up nearly a million new members a week, helped by its effective use of social media and technology.

The "Kejriwal effect" has also led to politicians reducing their bloated motorcades and removing red lights, a frequent target during his Delhi election campaign.

The newly elected BJP chief minister in Rajasthan has gone further, promising that her slimmed-down convoy would even stop at red.

'Squandered moral authority'

Many of those joining the AAP believe it offers them a better chance of a political career than the established parties.

"With the Congress or BJP, you can wait years and you still won't get a ticket," says Prof Kumar, one of whose former colleagues is now a senior AAP figure.

Even if Mr Kejriwal is just a passing phase, the demands of the young will only become more powerful, with half of India's 1.2 billion population under 25.

"Deference is eroding everywhere," says Prof Bina Agarwal of Manchester University, and all politicians are on notice: "They have squandered their moral authority."

Some veterans of the Delhi gang rape protests are helping foster this activist mood.

Film director Ram Subramanium remembers being "inspired by the huge turnout" in his native Mumbai in 2012, and recently released a video encouraging greater participation in politics, entitled I Am Muted.

Some of those protesters never stopped.

Raman, a young lawyer, is still demonstrating for better women's rights every day in central Delhi, 14 months since the gang rape.

"It was a moment of political awakening for us," he says. "But unless we keep making our voice heard, India's future is dark."

- Published28 December 2013

- Published25 September 2013

- Published25 January 2013