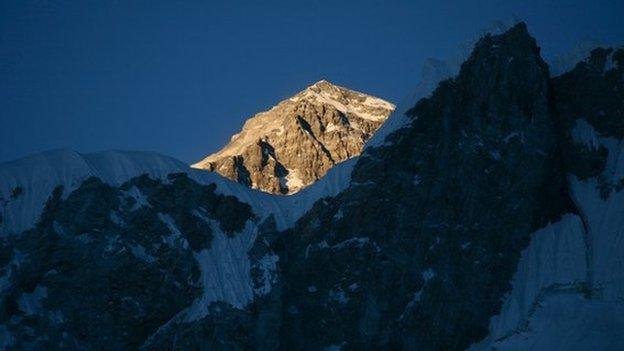

Sherpas count cost of 'ticket to Everest'

- Published

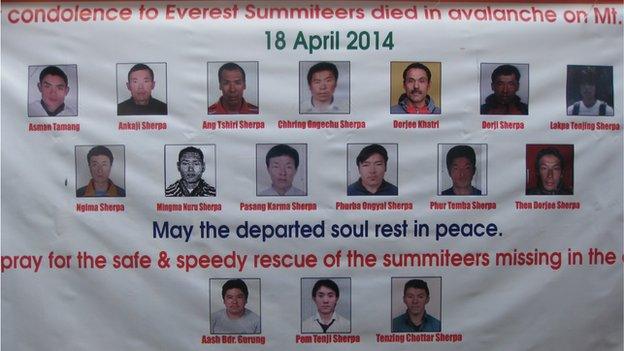

In the Sherpa heartland, people are still reeling from the avalanche in April that killed 16 of their men on Mount Everest.

It was the worst accident in the history of the world's highest mountain - and led to Sherpas walking off the job to demand better pay and conditions.

Despite the tragedy, people in the villages of Khumbu region say they have no choice but to go back to the mountain this autumn.

"I saw my brother killed by the avalanche almost in front of my eyes, I am still shaken," says Pema Chhepal Sherpa, whose brother Tenzin's body is one of three still missing.

Pema was in camp two, ahead of his brother, when disaster struck in the dangerous Khumbu Icefall area near Everest base camp.

"But I know I will have to be back on the mountain next climbing season because I have no other job and Everest means money," he says, fighting back tears while nuns perform puja (prayers) for his brother's departed soul.

Pema's dilemma is one facing many Sherpa climbers.

Pema Sherpa lost his brother in the avalanche

But their bigger concern is that despite the boycotting of expeditions by hundreds of Sherpas since April, there is the real prospect of little or no change.

They say the business of mountaineering largely exploits Sherpa climbers who are in the frontline of this lucrative industry.

Following widespread criticism of its initial plan to pay $400 in compensation to each family of those who died in the avalanche, Nepal's government raised that sum more than 10 times. It also announced it would require expedition operators to raise the amount they insure their Sherpas' lives for from $10,000 to $15,000.

The government earned nearly $3.5m in royalty fees from mountaineering in 2012 and nearly 80% of that was from expeditions to Everest.

The BBC visits Everest's Sherpa heartland months after an avalanche killed 16 guides

Although the government was accused of not taking the crisis seriously to begin with, members of the Sherpa community say operators should also take the blame.

"Most of these Sherpas are young and uneducated boys who are more often exploited by expedition agencies," Dawa Sonju Sherpa told me in Namche, the gateway to Everest base camp.

"These agencies make them do more than 70% of the work while they are paid not even 10% of what expedition agencies earn from the clients."

Sherpa climbers say they still get too little from their employers

Namche Bazaar relies heavily on money made from those who come to Everest

The climbing industry offers a better paid alternative to yak farming

Mingma Sherpa says he doesn't know how much his agency charges clients

Sherpa climber Mingma, who narrowly escaped the 18 April avalanche, said workers like him didn't know how much expedition agencies charged their clients for the services they provided.

"We never have such information but what we are paid in one climbing season is much less and does not support us for even a few months."

Available figures suggest a Sherpa climber on average earns about $5,000 during a climbing season, of which there are two a year - spring and autumn. That's much higher than Nepal's per capita income of about $650.

Against that, some operators can earn up to $80,000 from just one client, of whom there may be dozens a year.

International expedition companies say they pay Sherpas handsomely but many Nepalese firms that recently joined the market cut prices, and as a result some Sherpa climbers' pay has suffered.

Ang Tshering Sherpa, president of the Nepal Mountaineering Association, also makes that point.

"You better ask the Expedition Operators' Association of Nepal to make similar standards as that of international operators - that is the most important thing," he told the BBC, insisting his own company was already doing that.

The expedition operators' president, Dambar Parajuli, admitted there was cut-throat competition and that a minimum standard had to be maintained.

"But all is not well with foreign expedition companies as well. We don't know how much they earn from the expedition groups they bring to our Himalayas and how much of that money comes to Nepal."

Two months after the avalanche, the government and expedition agencies are still at odds over the proposal to increase Sherpa insurance, and everyone's blaming each other.

The government agrees "outdated" mountaineering regulations should be reviewed.

"But the Sherpa climbers are employed by the mountaineering community including from foreign countries - it is their responsibility to take care of them," argues Finance Minister Ram Sharan Mahat.

No-one's holding their breath.

The group of 16 Sherpa climbers were hit as they made preparations for the climbing season

So, those like Dawa Sherpa, who was seriously injured by the avalanche, are not hopeful of any major change.

"We fix ropes and make trails, we carry loads, we guide climbers to the top and then it is us who has to do rescue work as well," he said, showing me the ribs he broke in the accident.

"I wish our working conditions changed but I know this is not going to happen."

Frits Vrijlandt, president of the International Climbing and Mountaineering Federation, thinks the main problem is the endless demand for Sherpas from foreign climbers, many of them inexperienced.

"Now everybody wants to buy the ticket to the summit and the Sherpas do all their work and they just go up.

"Huge loads of Sherpa support is necessary for all the inexperienced foreign climbers to go up Everest.

"These people, they need oxygen from a very low level, they don't carry anything themselves, the Sherpas carry all their loads and most of them are quite unnecessary things."

Mingma Lhamu has lost two sons on Everest in the last three years

On average, more than 30 expedition teams go to Everest every year - last year 562 people reached the summit.

Mountaineering experts believe that figure is bound to increase because more and more people from around the world want to go to the highest point on Earth.

Sherpas know this global industry depends on them, but they still have little power.

Even though they brought the last climbing season to a halt, they say they will still have to go back to work.

In Furte, a small settlement in Khumbu, Mingma Lhamu Sherpa sits at her doorstep trying to come to terms with losing two sons on Everest in the last three years, one of them in the April tragedy.

"Working for Everest expeditions seems to have become more dangerous, but what can we do?" she says.

"For the need of money, sons will continue to go and die there while mothers are left back crying."

Listen to Navin Singh Khadka's report for Assignment on the BBC World Service on Thursday - or catch up later on the BBC iPlayer. The documentary will be broadcast on BBC World from 20 June.

- Published8 May 2014

- Published25 April 2014

- Published25 April 2014

- Published22 April 2014

- Published14 February 2014