Can Pakistan's new ISI spy chief Rizwan Akhtar restore security?

- Published

Gen Akhtar (left) is thought by some to consider militancy a greater threat than India

Pakistan's army has chosen a new head of the country's controversial spy agency. Seen as experienced in counter-insurgency operations, Lieutenant-General Rizwan Akhtar is being called "a professional soldier". But as M Ilyas Khan reports, the question is whether he will be able to restore internal security.

Lt-Gen Akhtar's appointment as head of Pakistan's feared Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) makes him the second most powerful man in the military - and possibly in the country, some would say - after the army chief.

It also puts him in at the deep end of a situation which is marked by fundamental shifts in the regional security arrangements and political instability at home.

He was commissioned in the Frontier Force (FF), an infantry regiment of the Pakistani army, in 1982. He is the sixth consecutive ISI chief to have been drawn from the infantry. He is said to have had a good academic as well as operational background.

According to the Inter Services Public Relations, the media wing of the army, Gen Akhtar is a graduate of the Command and Staff College Quetta and the National Defence University in Islamabad.

He also attended a war course at the US Army War College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

'No political ambitions'

He has held various positions in counter-insurgency operations in the north-western tribal region and in the southern city of Karachi - both plagued by militants, sectarian and ethnic death squads and crime gangs.

As such, many believe he brings the right mix of field experience to an intelligence agency which has been central to security issues not only within Pakistan, but also across a wider region in South Asia and elsewhere.

The ISI often plays a very public role in society, sometimes getting involved in politics

His appointment on Monday was greeted by the usual comments. "He is a professional soldier," said a line in one newspaper report. "He is every inch a soldier and has no political ambitions," said another.

Reuters quoted one military source as saying Gen Rizwan "is a horribly straight guy, all black and white. He has served in a place like Karachi, with all its turf wars and politics, while remaining neutral and apolitical".

He is described by many as hailing from a new breed of army officers who consider militancy a greater threat to national security than Pakistan's arch-rival India.

He is also portrayed as someone who believes in a civilian-dominated political process in which the military's role should be confined to defence against external enemies.

Most of this is based on a 33-page dissertation he submitted in March 2008 as part of a degree course in strategic studies at the US Army War College.

But in a country like Pakistan, which has a history of military coups, these are just expressions of optimism that a certain army officer will not indulge in political intrigues to destabilise a civilian government.

Mired in controversies

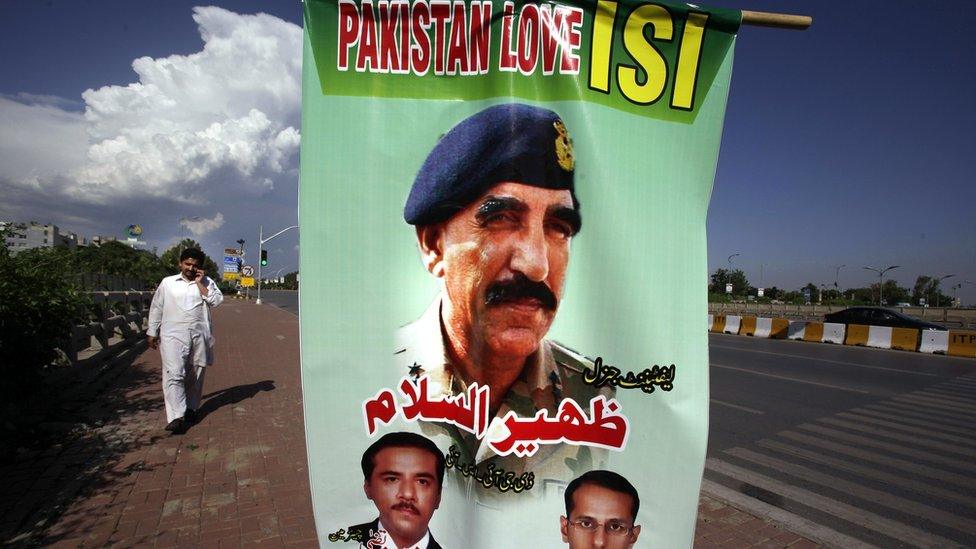

Come 8 November, when he takes over from Lt-Gen Zaheerul Islam who is retiring, Gen Rizwan Akhtar will be stepping into the shoes of men whose choice of keeping a high or a low profile in this powerful office has depended not on their personal traits and beliefs but on whether the country was ruled by the military or civilians.

During the 1977-1988 military regime of General Zia ul-Haq, for example, there were no tensions between the government and the ISI.

How will Gen Akhtar view the current protests against PM Nawaz Sharif (right)

But in the following years when democracy was restored, then army and ISI chiefs were mired in a series of controversies involving the creation and funding of a political alliance, a conspiracy to buy off MPs during a confidence motion, and election rigging.

They again faded into the background when Gen Pervez Musharraf staged his 1999 coup. However, since Gen Musharraf's exit, the ISI has been back in the limelight.

Gen Ahmad Shuja Pasha, for example, made headlines when he turned down the government's orders to visit India and share intelligence in the aftermath of the 2008 Mumbai attacks.

He was also instrumental in collecting information, involving travels abroad, for what later came to be known as the Memogate scandal - accusations that Pakistan's civilian rulers requested help from the US to avert a possible military coup against the 2008-13 government of President Asif Zardari.

And most memorably, it was on his watch that Osama Bin Laden was killed on Pakistani soil by US special forces, to the huge embarrassment of the Pakistani military.

Gen Pasha's successor, Gen Zahirul Islam, is widely accused of organising the current anti-government protests because Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif stood by a TV channel when it blamed Gen Islam and other ISI officials for the 19 April shooting of one of its talk-show hosts.

Anti-militancy strategy

Many will be closely following Gen Rizwan Akhtar Nato's planned exit from Afghanistan

Many say Gen Rizwan Akhtar is likely to act no differently.

He steps into office at a time when there is a civilian government in power, and it is already under siege from two opposition groups.

And then there is the crucial question of Nato's planned pull-out from Afghanistan over the next three months. So, "what's in store for the ISI and its meddling in Afghanistan and the Taliban?" asks The Nation newspaper in an editorial.

The paper points to a controversy last year when as head of the paramilitary Sindh Rangers in Karachi, Gen Akhtar testified before the Supreme Court that a shipload of arms and ammunition brought in as Nato supplies had gone missing in Karachi.

Was this an insinuation that the Americans were arming insurgents in Karachi? Or was it a suggestion that someone who wielded influence in Karachi and had a use for those weapons stole them? At the time it was read by many as an accusation against the Karachi-based MQM party.

There have been repeated, though unproven, allegations that Gen Akhtar worked with elements from the Pakistani Taliban to surround and limit the influence of what is said to be the armed wing of the MQM.

As such, while the top ISI office may continue to dabble in politics, a more appropriate yardstick of Gen Akhtar's performance would be whether he goes for an anti-militancy strategy that leads to the restoration of internal security.

A crucial factor in achieving this would be the extent to which Gen Akhtar can prepare the military leadership to reconcile itself to the fact that improved internal security could lead to a diminished political role of the military - and thereby threaten the long-term interests of its vast business empire.

- Published22 September 2014

- Published3 May 2011

- Published30 April 2014