Moon Jae-in: Big tests ahead for South Korea's new leader

- Published

Mr Moon favours greater dialogue with North Korea, a change to current policy

The outcome of South Korea's presidential contest, while not quite an electoral landslide, certainly represents a seismic shift in the country's political centre of gravity.

Moon Jae-in's success in winning the contest with some 41% of the vote, while not a foregone conclusion, confirmed the expectations of many observers that the population would move leftwards rejecting the trend of the past eight years that has seen conservative candidates occupying the presidential residence, or Blue House, since 2008.

At 64 years old, Mr Moon's personal biography epitomizes South Korea's progressive politics and the civic activism that shaped the democratization movement that transformed the country in the 1980s and 1990s.

The eldest son of North Korean refugees who fled south in 1950 at the height of the Korean War, Mr Moon grew up in poverty, and like many of his generation spent his student days actively protesting against the authoritarian government of Park Chung-hee who dominated the country from 1961 to 1979.

Trained as a human rights lawyer, Mr Moon spent the 1980s working with Roh Moo-hyun - another progressive lawyer, who would himself go on to become president in 2003 - opposing the military regime of Chun Do-hwan, Mr Park's successor.

The personal connection with Mr Roh allowed Moon Jae-in to secure a ring-side seat in the Roh administration, ending up acting at the president's chief of staff and paving the way for his eventual rise to prominence as the lead of the Democratic Party, the country's main opposition force.

Inside: Calls for reform

Mr Moon's experience of challenging the establishment has made him the natural candidate for the broad cross section of Koreans who pushed for the impeachment of his predecessor, Park Geun-hye (the daughter of the former dictator), now incarcerated and on trial for a range of offences including seeking to extort $70m (£54m) from the country's economic conglomerates or chaebol.

Mr Moon's key political challenge will be to realize the political aspirations of the populist, reformist movement that swept Ms Park from power and which is eager to see the transformation of the corrupt, elitist corporate and political culture that has dominated the country for many years.

Mr Moon is set to face critical obstacles in a post-impeachment era

Post-war economic development was premised on a narrative of collective hard work and national unity and the belief that all Koreans would be the beneficiaries of rapid growth. Today, however, this image of common endeavour and gain has been challenged by widening wealth disparities and narrowing professional opportunities, especially for young Koreans.

Mr Moon's reputation as a pragmatic and experienced politician should help him grapple with this challenge, but he will face a number of critical obstacles.

The unique circumstances of the impeachment crisis, means he has no transition period in which to appoint key allies to leading government positions, and he will need initially to work with bureaucratic and political appointees from the previous administration.

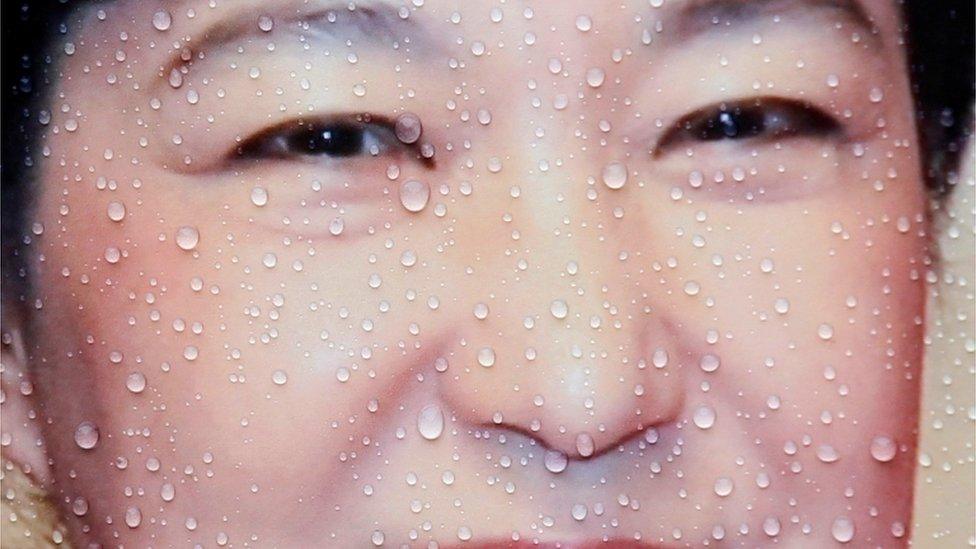

Park Geun-hye was impeached amid a big political scandal

In the national assembly, his allies in the Democratic Party have a plurality but not a majority of seats, and Mr Moon will need to build a coalition of support to offset the influence of the conservative Liberty Party that occupies 35% of the seats.

Needing to reach out across the political aisle, Mr Moon has already announced that he "will become president of all the Korean people".

However, rhetoric is easy (Ms Park said much the same thing when she became president in 2013), and Mr Moon will need to lower expectations of an immediate, radical transformation of the country's political and corporate culture - not least because many of the privileges and abuses associated with the country's elites are also to be found more widely distributed throughout society as a whole.

Outside: A plethora of challenges

If domestic reform was not enough of a problem, Mr Moon will confront a plethora of foreign policy challenges.

Top of the list will be confronting the nuclear threat from Pyongyang. This involves not only deflecting Kim Jong-un, the 33-year-old North Korean leader, from his single-minded pursuit of nuclear and ballistic missile tests, but also finding a constructive way of working with US President Donald Trump who appears to share Mr Kim's predilection for military sabre-rattling, brinkmanship and unilateral decision-making.

At the top of the new president's agenda is how to deal with Kim Jong-un and the North Korean issue

Mr Moon walked a narrow tightrope during the campaign, making clear his preference for engagement and dialogue with the North, but avoiding any overtly confrontational stance towards Washington.

The South Korean left has a long history of anti-Americanism, but Mr Moon's experience of government under President Roh is likely to make him wary of needlessly antagonizing Washington even though he will eventually want to distance himself from the more hawkish and uncompromising approach adopted by the new US administration.

Ultimately, the road to Pyongyang runs through Beijing, not least because China provides the bulk of North Korea's energy and food supplies. The recent deployment to South Korea of US Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (Thaad) missile defence batteries has polarized Sino-South Korean ties with the Chinese government clumsily discriminating against leading South Korean firms and seeking to bully Seoul into reversing its decision.

Mr Moon will want to keep Beijing on side, in order to help secure movement with Pyongyang, but without compromising the autonomy and sovereignty of his new administration.

Another potential source of bilateral tension will be with Japan. The administration of PM Shinzo Abe favours a hawkish posture of maximum deterrence and pressure on North Korea and appears supportive of Mr Trump's high-stakes approach, confident perhaps that it is not in the front line of any immediate military fall-out if the situation deteriorates into a physical conflict.

For the South Koreans, a more accommodating posture may be more attractive given the exposure of Seoul and its 20 million inhabitants to the North's short-range artillery. Also, bilateral historical tensions over the status of Korean "comfort women" - sex slaves from the Japanese pre-war colonial period - are likely to be back on the diplomatic agenda as progressive politicians in the South lobby to re-open an issue that will almost certainly prove extraordinarily challenging for the new president.

Ultimately, Mr Moon will need considerable diplomatic flexibility, negotiating guile, and policy-making foresight to confront these challenges - not so much a case of completely defying political gravity, but at least finding a way of floating above the fray.

Dr John Nilsson-Wright is Senior Lecturer in Japanese Politics and the International Relations of East Asia, University of Cambridge and Senior Research Fellow for Northeast Asia, Asia Programme, Chatham House

- Published9 May 2017

- Published9 May 2017

- Published26 April 2018

- Published6 April 2018

- Published24 November 2016