North Korea tensions: Why clarity is key to avoiding a spiralling crisis

- Published

North Korea has put on elaborate military displays in recent days as tensions rise

Some 10 days ago, as tensions mounted on the Korean peninsula, a British newspaper ran a cartoon showing a smiling North Korean leader, Kim Jong-un, alongside a similarly smiling Donald Trump.

Under Kim Jong-un was the caption "unpredictable, oddly coiffed nutter threatens world with massive firepower". Next to him, the beaming President Trump was wearing a shirt emblazoned with a picture of the massive bomb, external that US forces had just dropped in Afghanistan, with the slogan "Been there, Done that, Got the T-shirt!"

It was an example, perhaps, of the cynicism Mr Trump's arrival in the White House has provoked among many western European commentators.

But for many outside observers, there are good reasons to worry. Both leaders - albeit in their different ways - are seen as unpredictable and inexperienced. Both have mounted a war of words against the other. And both are busy sending military signals which, intended or not, are raising the risk of war.

However, what needs to be explained is: why now? What has suddenly prompted this escalating tension? And is a conflict really a possibility?

In its bellicose statements North Korea is in many ways behaving true to form. This is a regime, after all, that in recent years has sunk a South Korean warship and shelled the territory of its neighbour.

Its recent artillery exercise was a clear reminder to South Korea that its capital - Seoul - is easily within range of massed North Korean guns.

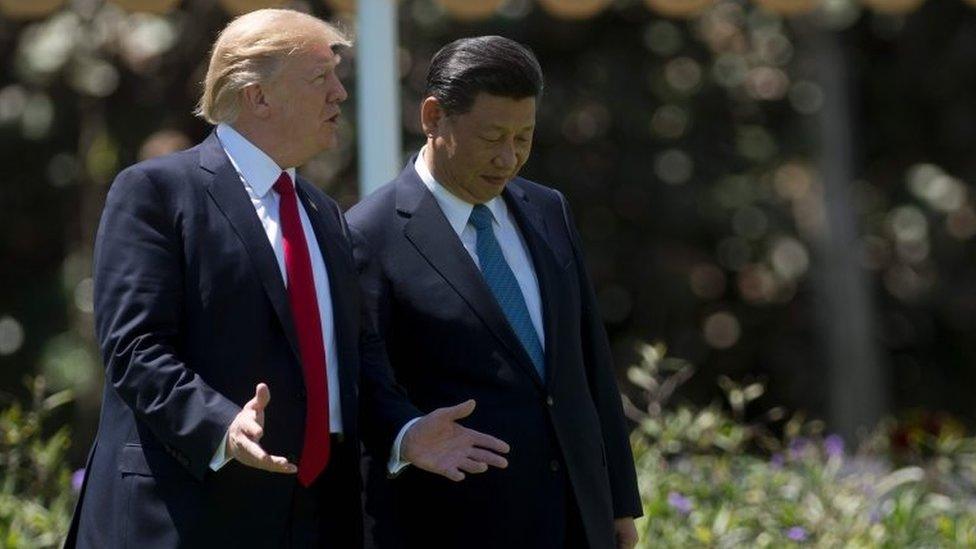

Kim Jong-un and President Trump have something in common - both are hard to predict

But in this present crisis Pyongyang clearly feels threatened. The signals coming from Washington are strong, but they are also mixed; and mixed signals inevitably carry the risk of misunderstanding and potential catastrophe.

Confused signals

On the face of it, the Trump administration has taken exception to a continuing programme of North Korean missile tests and the possibility of the forthcoming testing of a nuclear device. In themselves these are nothing new.

Past US administrations have similarly had to contend with North Korea's developing nuclear effort and its desire to build ever-longer range missiles, which one day might even threaten the continental United States.

But the Trump administration is different. It believes that a moment of crisis is approaching; that North Korea's technical progress is such that weapons with an inter-continental range are not a long-term pipe-dream for Pyongyang, but a fast-approaching reality.

It believes that China still holds the key to restraining the North Korean regime, and so ramping up the pressure sends a message as much to Beijing as it does to Pyongyang.

South Korea has carried out its own large-scale military drills, which Seoul says are defensive in nature

Thus the US is deploying its Thaad anti-missile system in South Korea and is engaged in anti-ballistic missile exercises with the Japanese navy.

A US aircraft carrier - the USS Carl Vinson - and its strike group is heading towards waters off the Korean peninsula, and the USS Michigan, a cruise missile carrying submarine, has very visibly docked at a South Korean port. But what exact message is all this sending?

Comments by the US ambassador to the UN, Nikki Haley, earlier this week illustrate the problem.

She made it clear that if North Korea attacked a military base or launched an intercontinental missile, then US military action might follow.

But when pressed by her interviewer, she went on to urge Kim Jong-un not to conduct a nuclear test or to fire any more missiles, rather muddying the waters and leaving it unclear as to just what might prompt a US military response. Signalling is all very well, but clarity is also crucial.

Message to Beijing

China is receiving the US messages loud and clear and shows some sign of trying to pressure the North Korean regime to the extent that it can.

But there is also a discernible sense of alarm in President Xi Jinping's comments - a fear that things could so easily get out of control.

China, of course, is unhappy at the deployment of US Thaad anti-missile defences in South Korea - probably because it fears their powerful radars will to some extent compromise the capability of China's own nuclear deterrent.

But the message to Beijing is also that the US will stand by its allies in the region with whatever capabilities are necessary. And that, too, is concentrating Chinese minds.

President Donald Trump (left) says the US can solve the North Korea crisis without the help of China

Unconnected with all this is the launch of the Shandong - the Chinese navy's first locally-built aircraft carrier.

It is expected to enter service around 2020. It is similar, though perhaps slightly larger than the Liaoning - China's first carrier, which was adapted from a partially-built Soviet warship - the Varyag. Its launch marks a significant step for the Chinese navy, which is rapidly modernising.

However, while China's experience with its "training" carrier - the Liaoning - has been hugely beneficial, developing a true carrier strike group and integrating all the aspects of naval power within it will take some years.

It is a signal, though, of the direction in which China is going and of its desire to be able to project maritime power well beyond its shores. Beijing, after all, is simply following the US navy.

After all, in this Korean crisis, President Trump's first thought was to despatch a carrier. As we now know, it took some days for the USS Carl Vinson actually to change course, suggesting again some worrying uncertainties about the way the Trump administration conducts its business.

- Published4 July 2017

- Published21 April 2017

- Published10 August 2017

- Published10 August 2017