North Korea: How are countries defending themselves?

- Published

Nuclear N Korea: What do we know?

North Korea's nuclear weapons programme has progressed faster than predicted, threatening the security of nearby nations – and potentially the United States.

The US envoy to the United Nations put it simply: "Despite our efforts over the last 24 years, the North Korean nuclear programme is more advanced and dangerous than ever."

Analysts tend to agree that the country's leader, Kim Jong-un, is seeking a nuclear deterrent rather than an all-out war - but other nations are not taking chances.

So how do you defend against a politically isolated state with nuclear ambitions, when diplomacy, it appears, simply does not work?

South Korea

South Korea is the closest potential target.

The other half of the Korean peninsula has a long history of preparing to defend itself from its northern neighbour. The two countries are technically still at war, having never signed a peace treaty when the Korean War ended in 1953.

The Thaad system - seen here in testing - is one of several anti-missile defences

One key part of its defensive line is the Demilitarised Zone (DMZ) - a region 250km (155 mile) long and 4km (2.5 mile) wide that separates the two nations, guarded by thousands of soldiers, lined with barbed wire fences, and filled with landmines.

But it is believed that North Korea's People's Army - with more than a million regular soldiers and millions more reserve troops - has drilled extensively on how to invade across the border.

And the heavy land border fortifications do nothing, of course, to prevent a missile strike.

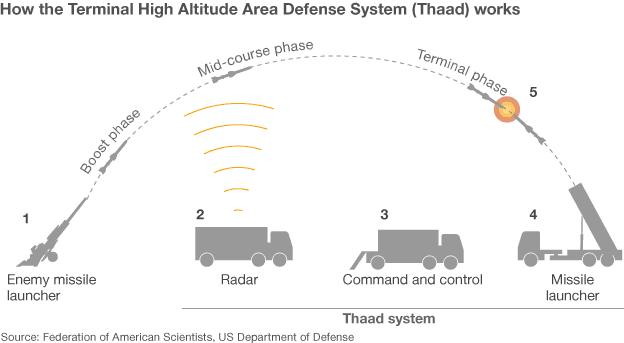

For a while, it was thought that Thaad - the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense - might be South Korea's best counter to a nuclear attack.

Thaad, funded by the South's military ally the United States, is designed to shoot down ballistic missiles as they descend in the final phase of a strike. The complex technology was first deployed in May 2017, and has been successfully tested.

But the politics of South Korea's relationship with the North means its rollout has not been easy.

North Korea and its only ally China both see Thaad as a provocation, and many South Koreans living near the places its was deployed fear it could be seen as a military target.

The South's new president, President Moon Jae-in, suspended the rollout of the system in June, saying an environmental impact analysis was needed.

But in light of recent nuclear tests, the South's defence ministry has now said it will deploy the four remaining Thaad launchers that had been delivered, in addition to the two already operational.

Japan

At its closest point, Japan is just a little over 500km (310 miles) from North Korea - well within striking distance.

In August, Pyongyang fired a missile directly over Japan, in what Prime Minister Shinzo Abe called an "unprecedented" threat to his country.

The close proximity of the two nations means that Japan has only minutes to respond to any launch. During the August missile test, people had about three minutes from receiving the emergency warning until the missile flew overhead. Many only learned about the threat later in the day.

In terms of defence options, Japan utilises the Patriot missile system which, like Thaad, is designed to shoot down incoming missiles. But it has a limited operational range, making it effective at defending key locations - and not the entire country.

But Japan does not have to worry about land invasion to the same extent North Korea does, and at sea, it has other options at its disposal.

Securing the seas

Japan, South Korea, the United States are among the countries with the Aegis naval defence system.

Aegis is yet another anti-missile system, but unlike Thaad or Patriot defences, it can also be deployed to ships patrolling the seas in the region.

A test missile fired by the US on August 29, left, was shot down by the Aegis system similar to the file photo, right

Those battleships come equipped with powerful radar which could detect the launch when deployed near the North Korean coast. They are also fitted with guided missiles, and could attempt to shoot down the incoming missile - or share its tracking data with another missile defence system closer to the target.

There are a handful of problems with the system, though. Aegis ships need to be deployed in the right place at the right time - and while they have been tested extensively, they have never been used to defend against an actual launch.

United States

For years, the best defence for the US was its sheer distance from North Korea - some 5,000km (3,100 miles) to Alaska and almost 9,000km to San Francisco. But rapid advancements mean that distance might no longer be far enough.

North Korea's military wants the capability to shrink a high-yield nuclear warhead to fit on an inter-continental ballistic missile (ICBM). In theory, that would allow Pyongyang to strike the United States.

See the US anti-missile system in action

After its latest test, North Korea claimed it had managed to shrink the warhead, posting photos of what it said was a hydrogen bomb - in keeping with a Washington Post report from early August, external.

That means the US is now reconsidering its missile defences, with President Trump having ordered a review of the entire system.

It already has detection and interception systems. But critics believe that the US system is far from reliable, the BBC's diplomatic correspondent Jonathan Marcus wrote in July.

In the foreseeable future, only a handful of its interceptor missiles will be available to deal with the potential North Korean threat, he said.

And it also has to worry about its overseas territory of Guam - a key military outpost in the Pacific which has been singled out by North Korea as a threat to be "contained".

That island already has a Thaad system deployed, but state media says Kim Jong-un has already been briefed on strike plans - and is waiting to see the next US actions.

- Published4 September 2017

- Published21 April 2020

- Published3 September 2017

- Published29 April 2018

- Published4 September 2017

- Published15 September 2017

- Published4 July 2017

- Published7 June 2017