Hun Sen: Cambodia's prime minister prays for good fortune

- Published

What did ordinary Cambodians make of the "peace" ceremony at Angkor Wat?

Confused tourists found themselves being turned away by police officers this weekend from the old main gate of the spectacular temple of Angkor Wat.

This view of the 12th Century stone ruins, one of the most popular destinations in Asia, had been commandeered as a backdrop to an impromptu ceremony, ordered by the man who has run the country for more than three decades.

Prime Minister Hun Sen described the event as a prayer for peace and unity. And when Hun Sen orders something, it gets done in style.

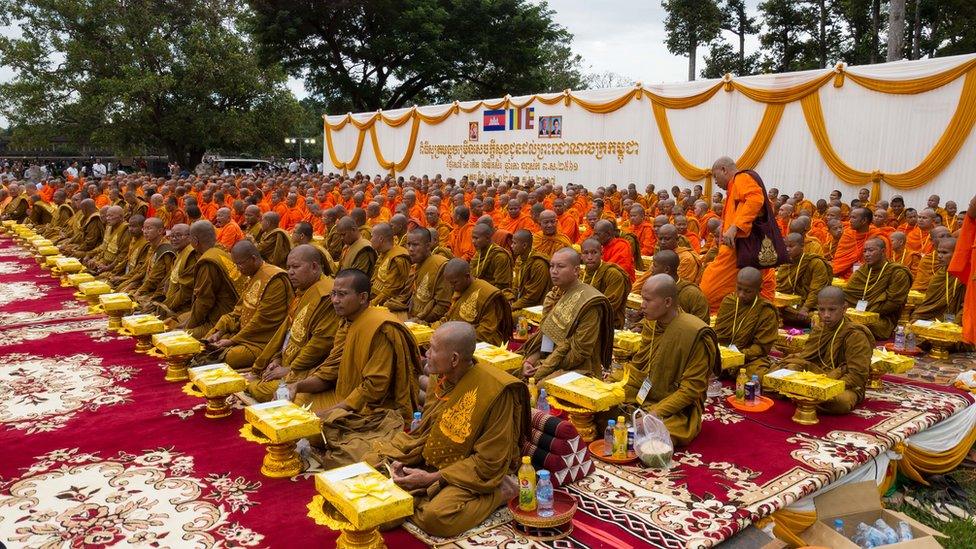

Thousands of orange-robed monks trooped in for the two-day event, along with schoolchildren, boy scouts and crowds of local people, dressed in white, as instructed.

Thousands of orange-robed monks attended the ceremony ordered by Cambodia's prime minister

They were overseen by unsmiling security guards, who kept them well away from the prime minister's party.

Hun Sen's security detail are notoriously protective; when trying to film his arrival, you can end up with a few bruises from them pummelling your back.

A gilded shrine was erected next to the great moat of Angkor Wat, decorated with five-tiered umbrellas, a Buddhist symbol of celestial status. Huge rolls of red carpet were unfurled across the dusty road.

Neatly wrapped parcels were laid on gold dishes before which the monks would chant their blessings, with printed cards stating they were offerings from the prime minister.

Government ministers, and some of Hun Sen's business partners, the so-called "oknhas" or cronies, formed a reception line for him.

Hun Sen came on both days of the event, arriving without warning, with his wife, Bun Rany.

Hun Sen commandeered the popular tourist site as the backdrop for an impromptu ceremony

He walked slowly, apparently in some discomfort, greeting just a few of the guests, and had to be helped to sit down in front of the monks, where he leaned awkwardly against a cushion.

He appeared weary, and older than his 65 years. But he sat through two prayer sessions, a traditional dance performance and carried out two candle-lighting rituals with his wife.

Whatever ailments he has, it mattered enough to Hun Sen to see this ceremony through to the end.

Electoral challenge

The ordinary people who attended were told simply that the event was to bless their country. As devout Buddhists, they seemed happy just to be part of such an opulent display of piety.

But the timing was surely significant, following the most dramatic political developments for 20 years.

In June, the main opposition party, the Cambodian National Rescue Party (CNRP), performed well at the important local commune elections, despite threats, intimidation and a near monopoly of media coverage by the government Cambodian People's Party (CPP).

Prime Minister Hun Sen appeared weary during the ceremony

The CNRP did equally well in the last general election in 2013, claiming that it was denied victory only by widespread cheating.

It looked set to mount the most serious challenge to Hun Sen's hold on power since he became prime minister in 1985.

The government's response was to shut down unsympathetic media, arrest the CNRP leader Kem Sokha on a bizarre charge of conspiracy in a US-backed plot to overthrow Hun Sen, and then, last month, to dissolve his party.

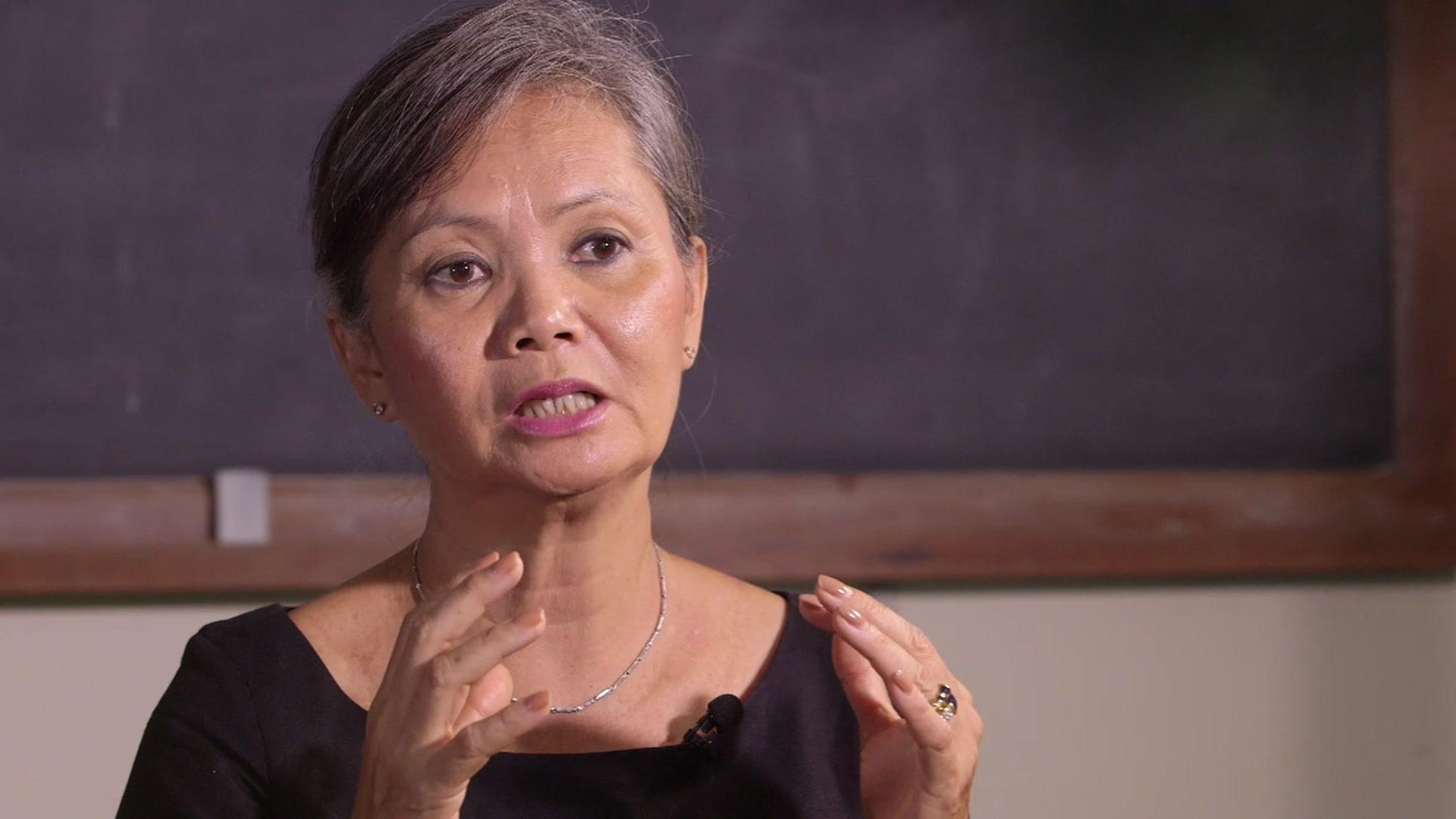

Most of its leading politicians had already fled the country, including Deputy President Mu Sochua.

"If he were sure of himself, he would not would not have to go all the way like this," she told me last week. "If he were sure of himself he would call us back and say 'let's compete freely, fairly, inclusively'. He is haunted by the need to hang on to power."

One-party state

Cambodia is now a de facto one-party state, heading for an election judged by the US and the European Union as illegitimate.

The post-Cold War project, of rebuilding a country on democratic principles in which the UN and its members invested many billions of dollars, lies in ruins.

In the US and the EU, there is talk of sanctions - something the CNRP is encouraging, however much they may harm ordinary Cambodians - as necessary pain for a better future.

Hun Sen is a poorly educated man from a provincial Cambodian town, who lost an eye fighting for the Khmer Rouge in the 1970s, then defected to Vietnam, which invaded in 1979, overthrowing the fanatical regime headed by Pol Pot.

He was appointed foreign minister at just 26 years old, and impressed his Soviet and Vietnamese patrons with his quick intelligence.

He has proven himself to be skilled at outmanoeuvring his opponents with a mix of inducement, intimidation, and occasional thuggish violence.

With his country heavily dependent on foreign aid just to run the government, he has allowed relative freedom to the media, political parties and civil society, while never allowing these to threaten his power. So why has he taken this drastic step now?

Chinese influence

One reason is China.

China is now Cambodia's largest aid donor, and has refused to criticise attacks on Hun Sen's opponents.

Western aid is relatively less important now, especially as the economy has grown quickly, offering substantial sources of income to Hun Sen and his cronies.

Six years ago, the prime minister ostentatiously declared his official income to the public, of a little over $1,000 a month.

In fact he, his wife and six children are thought to have amassed wealth worth hundreds of millions of dollars.

Leading opposition figure Mu Sochua says Hun Sen is "haunted by the need to hang on to power"

So suggestions that aid may be withdrawn in response to the dissolution of the CNRP carry less weight.

The EU and the US are, however, still the most important markets for Cambodian exports, in particular the textile and clothing industry, which has provided hundreds of jobs to poor Cambodians.

If the EU were to withdraw the preferential trade access Cambodia gets as a least-developed nation, it would have a devastating impact on the national economy.

But precisely because of that, the EU will be reluctant to take such a step, in a region where few countries uphold high democratic standards.

Instead, it might use targeted sanctions, aimed at a few top officials, which might inconvenience their families, but would not threaten their money or status in Cambodia.

Social media power

The other reason Hun Sen has dispensed with the democratic facade he has been willing to live with all these years is the country's changing demographics, and the arrival of social media.

On a narrow peninsula between the Mekong and the Tonle Sap Rivers in Phnom Penh, workers are constructing a huge monument in stone, with carved friezes, rather like the great temples of Angkor, depicting Hun Sen's achievements.

It focuses on what he calls his "win-win" policy, by which he persuaded the Khmer Rouge to give up fighting in the 1990s, and end the long civil war.

It is part of what appears to be a personality cult, with schools, hospitals, libraries and bridges named after the prime minister, who has added so many honorifics to his official title that few can remember how he should formally be addressed.

Hun Sen sits on top of a network of patronage which has significant interests in almost every economic activity in the country. In theory, he should be untouchable.

But most Cambodians were born after the war ended, and his "win-win" policy generally impresses only older people, who can remember the terrible years of conflict.

Younger people are more aware of today's endemic corruption, the massive disparity between rich and poor, and the injustice of practices like land grabs by well-connected businesses.

It is those younger people in particular who backed the CNRP, despite its woolly policy platform and sometimes fractious leadership.

The younger generations have mobilised through social media to express their protest

They used social media to mobilise support for the opposition, bypassing the CPP's near-monopoly of television and newspapers.

Time is not on Hun Sen's side.

The cronies who fund his party, and who have benefitted greatly from proximity to him, may at some point decide that a change of boss is necessary.

An aura of power still surrounds Hun Sen. If there is one axiom for observers of South East Asian politics, it is never to underestimate the Cambodian strongman.

By staging his prayer ceremony at Angkor Wat, the national symbol that has been used in every flag since the country's independence from France in 1953, he linked himself to the kings in Cambodia's greatest historical era, while at the same time portraying himself as the top patron of Buddhism.

Adept manipulation of such revered institutions can go a long way to sustaining legitimacy, in a country where harsh experience has instilled submission to authority in many people.

But as other authoritarian leaders, like Suharto in Indonesia, or even the late King Sihanouk of Cambodia, have shown, when that legitimacy falters, it can crumble very quickly.

- Published16 November 2017

- Published2 December 2017

- Published15 November 2017

- Published6 October 2017

- Published31 October 2017

- Published3 September 2017