Afghanistan: Where the road to peace is harder than war

- Published

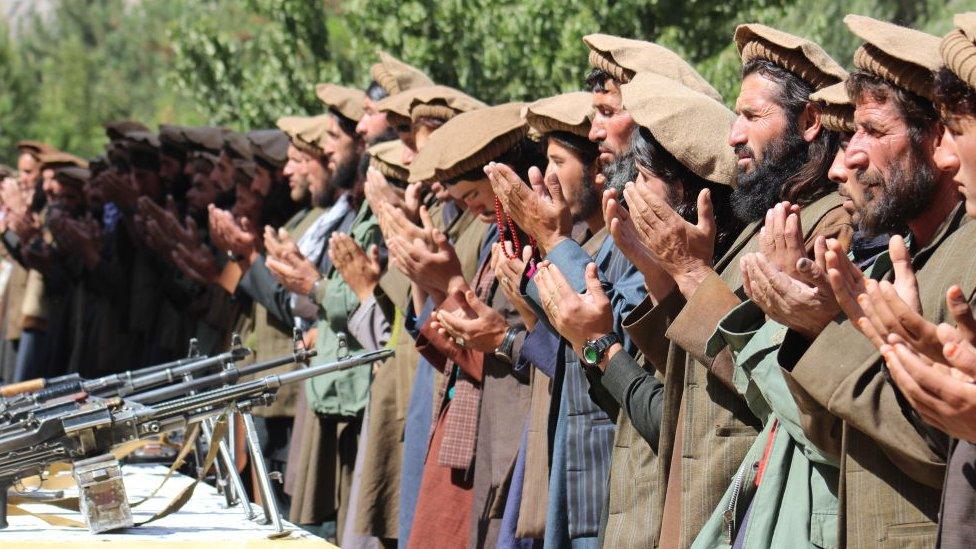

Peace protesters pictured after the ceasefire collapsed last year

"Peace is more difficult than war," the Taliban's lead negotiator, Abbas Stanikzai, told me during an interview back in February.

By then, representatives of the militant group had already held a number of rounds of discussions with US officials in Qatar, aimed at bringing an end to the 18 year-long conflict.

Those talks were seemingly brought to an abrupt and unexpected end in September by US President Donald Trump, just as an agreement was about to be signed.

Mr Trump questioned the Taliban's commitment to peace after they launched an attack that killed 12 people, including an American soldier, as initial details of the proposals were being released.

Taliban officials were shocked by the decision, countering that US forces had also been carrying out attacks as talks had been going on.

Some welcomed the move, warning that President Trump's repeatedly stated desire to cut costs and bring the roughly 13,000 US troops home risked handing Afghanistan back to the Taliban - leaving stranded those who had struggled to improve women's rights, create a free press, and build a nascent democracy.

Nine former US ambassadors to Afghanistan wrote a statement warning of the risk of "total civil war" if troops were withdrawn before a final peace deal.

President Trump met US troops in Afghanistan on Thanksgiving

Others warned that a rare opportunity to help bring an end to the violence was being missed.

Former senior US diplomat Robin Raphel was one of a small number of figures who played a crucial role in facilitating the start of the discussions, and told the BBC it was a "terrible mistake" not to sign the deal.

Ms Raphel and other analysts believe the US could have avoided years of conflict by talking to the Taliban shortly after overthrowing them in 2001: "We should have reached out to the Taliban after we ran them out of Kabul."

What's the situation now?

In the past few weeks, the talks have restarted. Both sides seem to acknowledge that a negotiated settlement is the only solution to ending the war, but what exactly that will look like is still the focus of discussion.

Sohail Shaheen, spokesman for the Taliban's political office, told the BBC the latest round of discussions continued to focus on the existing agreement which he said had already been "finalised" prior to President Trump's suspension of the talks.

Afghan government officials have been pressing for some form of ceasefire to be included in a revised deal, as what Habiba Sarabi, a deputy chair of the High Peace Council, described as a "trust-building exercise" designed to prove the Taliban retain control of their fighters on the ground.

One proposal understood to have been made by the US is some form of a ceasefire for a 10-day period around the signing of an agreement with the Taliban, which could then also set a positive tone for the start of separate talks between the group and other Afghan political figures.

Neither the proposal nor the Taliban's reaction to it have been public. One senior member of the group said they recognised the need to create a "conducive" atmosphere for peace talks but would not elaborate further. Another source suggested the Taliban was prepared to offer a "very short" universal ceasefire, and a longer ceasefire between the militants and US forces, but which wouldn't include Afghan forces. The source added Western and Afghan officials wanted the Taliban to agree to a longer pause in fighting with government forces.

There have been suggestions that an agreement is imminent, but such predictions have been proved wrong in past.

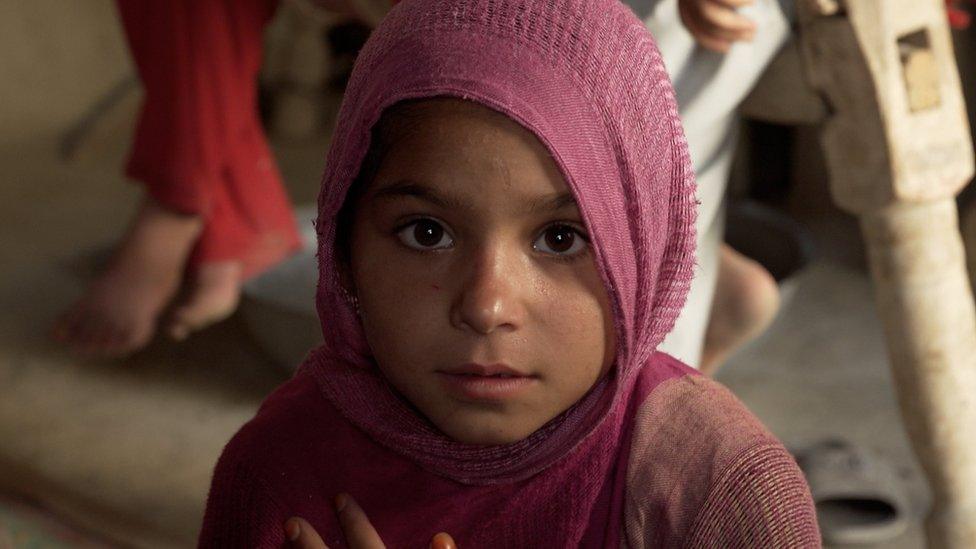

Meanwhile, the bloodshed continues. According to the United Nations, more than 2,500 civilians were killed in the first nine months of this year. Many say they feel caught in the middle of the conflict.

At a hospital in Kandahar province earlier this year, one man tearfully gestured to his baby nephew who had suffered third degree burns after their village was attacked and asked: "Who will take responsibility for this crime? The Taliban or the government? On the Day of Judgement, which of them will dare confess to this?"

Shocking scenes from one of the country's busiest hospitals in the southern city of Kandahar

Nevertheless, the fact the two warring parties continue to sit across the table from each other is, in the wider context of America's longest war, something of an achievement.

Whilst the Taliban control or contest a significant portion of territory, they have not been able to seize and hold any urban centre. Neither side looks capable of an outright military victory and they both appear to know it.

Concern has been expressed US troops might be withdrawn even without a deal in place. American officials have said the number of troops could be reduced by around 5,000 without affecting operational capabilities, but former diplomat Robin Raphel told the BBC that "any effort to remove the rest of the troops without a deal would meet with a lot of resistance".

How did Afghanistan get here?

The peace process was kick-started by two major developments in the summer of 2018.

The first was an unprecedented ceasefire during the Muslim festival of Eid ul Fitr. Taliban fighters streamed into cities, savouring ice cream and posing for selfies with members of the security forces.

Although fighting resumed immediately afterwards, it was a brief opportunity for both sides to see their enemies in a new light - as fellow countrymen rather than adversaries.

The other was the decision by the US to drop its condition that the Taliban must first negotiate with the Afghan government, rather than American officials.

The Taliban had consistently resisted this, dismissing the "Kabul administration", as they describe them, as "puppets".

Kai Eide, a former UN special envoy to Afghanistan, told the BBC the change in US policy was a "breakthrough". It led to a series of rounds of discussions between the US Special Representative for Afghanistan Reconciliation, Zalmay Khalilzad, and the Taliban in Doha, where the group's political office is based.

A group of Taliban soldiers sacrificed their weapons and joined the the Afghan government in September

But the Afghan government was clearly unhappy at their exclusion, and there seemed a fundamental disagreement in the talks.

The Taliban insisted negotiations revolve solely around their primary demand: a timetable for the withdrawal of foreign forces from Afghanistan.

In exchange they vowed not to allow international jihadist groups to operate in the country - a significant promise given the US rationale for overthrowing the Taliban was that they had hosted Al Qaeda.

But the Americans, perhaps wary of accusations they were abandoning their ally Afghan President Ashraf Ghani, initially insisted any deal would also incorporate "a comprehensive ceasefire", and the start of talks with the Afghan officials.

The Taliban said these issues would have to be dealt with after an agreement on troop withdrawal.

Again, it seemed the Americans were the ones forced to compromise.

What do the Taliban want?

Full details of the deal that was on the brink of being signed have not been made public. But from the outlines described by Mr Khalilzad, it involved the withdrawal of 5,400 US troops over 11 months, with some kind of reduction in violence in the areas they pull out from.

The Taliban would only agree that after the deal was signed, they would begin talks with a delegation of Afghan figures on the country's future, including, but not limited to, government representatives.

A ceasefire, the primary goal of most Afghans, would have been the first item of discussion of those talks, but there was no guarantee one would be declared. It was not clear if a further US troop withdrawal would explicitly depend on a ceasefire being agreed.

Taliban figures have in the past acknowledged their reluctance to agree to a pause in the fighting until all their aims are achieved, concerned that it might be difficult to motivate their foot soldiers to pick up arms having laid them down.

One Taliban source insisted if the original agreement were to be signed, it would reduce violence by 70-80% in the country, but he declined to name the specific terms in the agreement which would lead to that.

British troops left Afghanistan in 2014

Another attack by the Taliban close to the large American military base in Bagram during the latest resumed round of talks again led the US to question the Taliban's commitment to peace and the ability of the political office to speak for fighters on the ground.

The Taliban political office's spokesman, Sohail Shaheen, retorted that they could "ask the same question from the other side," referring to continued US attacks on Taliban targets during the discussions.

Other commentators say that in private the Taliban political leadership have at times expressed frustration with the timing of some of the bombings.

The addition to the negotiating team of Anas Haqqani, brother of a deputy leader of the Taliban, Sirajuddin, who heads the powerful Haqqani Network faction, is seen by some analysts as further bolstering the links between the Taliban's political and military commands.

Anas Haqqani was released by the Afghan government in a high-profile prisoner swap last month and flown to Doha.

But despite predictions by Afghan officials that hardline elements of the Taliban, angered by the peace talks, would split off en masse to join the Islamic State, the Taliban, outwardly at least, have remained unified, boosted perhaps by the knowledge that President Trump clearly wants to begin to withdraw his forces ahead of next year's election.

Time, as they are fond of saying, is on their side.

What about the election?

Complicating the picture within Afghanistan is the dispute over the country's own presidential election.

On Sunday, three months after the vote, preliminary results were announced, with incumbent President Ashraf Ghani set to be re-elected. However, his chief rival, Abdullah Abdullah is alleging fraud.

Former UN Special Envoy Kai Eide told the BBC it was vital a stable government emerged at this "critical stage" as a lengthy, and potentially violent dispute would be "the worst possible background for real [peace] talks".

Mr Ghani had hoped the elections would give him a strong, clear mandate, which he could use as leverage in any discussions with the Taliban after they reached a deal with the US. A low turnout and contested results make that more difficult.

Recounts of the 2019 election ballot continued into December

Those talks, between the Taliban and other Afghans about the future system of governance in the country, will be an even bigger challenge than the negotiations with the US.

One leading Afghan official who met representatives of the group earlier this year told me he believed they favoured a theocracy along the lines of the system in Iran.

For some Afghans, weary of the bloodshed, and disillusioned with what the last two decades have delivered, that would be a price worth paying for peace. For others, it would mean all the sacrifices made during those years were in vain.

Similarly for the Taliban, whose fighters have been struggling to re-establish an "Islamic Emirate," how easy would it be to transform into a purely political group working within a democratic system?

Their leaders are wary of the example of another Afghan Islamist figure, Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, who laid down arms in 2017 but has struggled to remain politically relevant.

In many ways it seems true peace, or the path to it, is more difficult than war.

- Published30 September 2019

- Published14 September 2018

- Published3 September 2019

- Published14 July 2019

- Published6 July 2019

- Published16 September 2019

- Published12 August 2022

- Published8 September 2019

- Published3 September 2021

- Published30 August 2021