Why a media mogul was arrested in Pakistan

- Published

Shakilur Rahman has been arrested and remanded in custody for 12 days

The authorities in Pakistan have arrested one of the country's leading media magnates on charges he illegally obtained government land more than 30 years ago.

Mir Shakilur Rahman is the editor-in-chief of the Jang group which owns some of Pakistan's most widely circulated newspapers, as well as the popular Geo television network.

The arrest is being seen by journalists and human rights activists as more evidence that free media and political dissent are being silenced in Pakistan.

Mr Rahman, who denies the accusations against him, appeared in court on Friday and was remanded in custody. He has not been formally charged.

What was Mr Rahman detained for?

The charges against him relating to the purchase of several plots of land in Lahore go back to 1986.

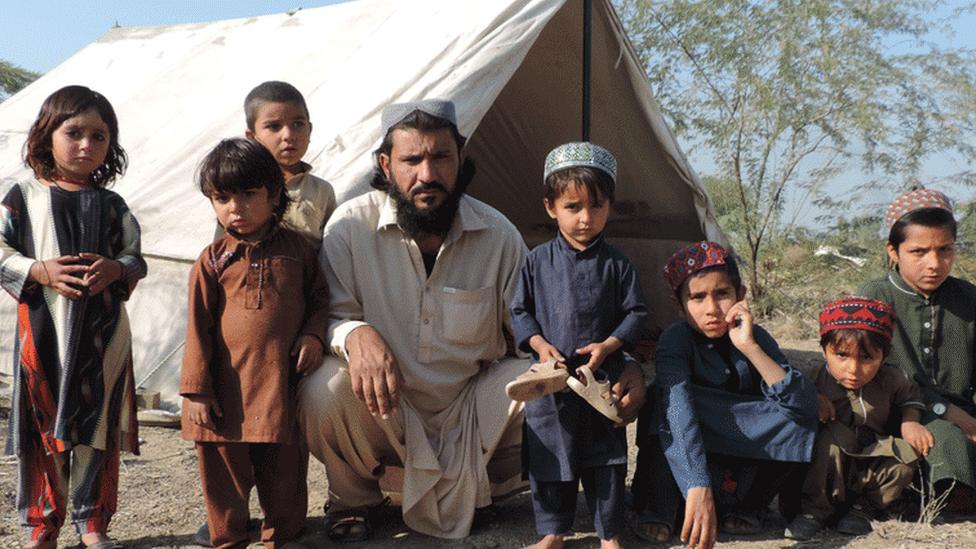

Shakilur Rahman owns one of Pakistan's largest media groups

Pakistan's anti-corruption agency, the National Accountability Bureau (NAB), has alleged that in that year, when future PM Nawaz Sharif was chief minister of Punjab province, he let Mr Rahman illegally acquire more government-owned-land than he was allowed by law.

Dawn newspaper quoted a NAB official as saying Mr Rahman was entitled to four acres of land under the Lahore Development Authority's "land exemption policy", but he acquired more than 13 acres.

NAB says this was illegal and amounted to a political bribe.

Mr Rahman says he bought the land from a private party and paid all the necessary taxes and duties, for which he has documents. He also says the purchase is a civil matter and therefore beyond the writ of an anti-crime agency like NAB.

Is that what it's really about?

Irrespective of the merits of the case, many doubt NAB is carrying out its duties honestly. It often takes action against those who question government policies.

The arrest has triggered widespread criticism from journalists' bodies, rights groups and the political opposition.

The Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP) has expressed "deep concern" over the arrest.

Jang has more on-the-ground reporters across the country than any other media group

"There remains a strong suspicion that such actions by NAB are selective, arbitrary and politically motivated," HRCP tweeted. "The journalist community sees this as yet another attempt to gag a beleaguered independent press."

The Pakistan Broadcasters' Association (PBA) pointed out that "arresting the editor-in-chief of a media house while the case is still under inquiry… appears to be an attempt at harassment".

Mr Rahman's daughter, Anamta, called the arrest "illegal, even by NAB's rules".

"This is a fight for freedom of media," she told the BBC. "Today it's the editor-in-chief of Jang - tomorrow it can be anyone."

Jang Group is Pakistan's largest media house, with more on-the-ground reporters across the country than anyone else, giving it a clear edge in Pakistan's increasingly competitive media environment.

In recent months, top anchors of its Geo television network have given government officials a hard time in interviews on a number of occasions.

Requesting anonymity, a veteran journalist in Lahore told the BBC that while there may be some truth in NAB's allegations, "there's no doubt it's a selective move because evidence of illegal financial activities by owners of the so-called 'friendly' media have also been cropping up from time to time but NAB doesn't seem to be bothered".

How free is the press in Pakistan?

Not very - the country comes way down press freedom indexes, external. The media has come under increased censorship since 2018 when the military was accused of rigging national elections to bring Prime Minister Imran Khan's PTI party to power.

But backdoor moves to quell media voices had begun much earlier.

In 2014, a top Geo talk show host Hamid Mir was shot and badly wounded.

Hamid Mir said the ISI spy agency was behind the 2014 attack on him

No-one was ever brought to justice for the attack, and many suspected he was being punished for his vigorous coverage of missing persons in Balochistan province, where the army has fought an armed separatist insurgency for more than a decade.

Most disappearances are blamed on the military. Pakistan's media have stopped covering the issue.

In 2017, a number of social media bloggers critical of religious groups and Pakistan's powerful military went missing for several weeks. They were released afterwards, and most went abroad.

The following year, a well-known journalist and social media activist, Taha Siddiqui, who had been warned by the military authorities a number of times, was attacked on an Islamabad road in broad daylight.

He was able to escape from the scene but has since left the country and is living in France.

Since 2018, the media has come under a more comprehensive censorship.

This includes threats to individual journalists, and briefly or completely shutting TV channels or influencing cable operators to demote them in the channels list so fewer viewers find them.

How successful has NAB been in fighting corruption?

The bureau was founded in 2000 by Pakistan's former military ruler Pervez Musharraf to go after corrupt politicians, bureaucrats and businessmen.

But it was largely seen as an attempt by the military government to clip the wings of the two largest political parties at the time - the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N) of Nawaz Sharif, which Pervez Musharraf had overthrown in an army coup a year earlier, and the Pakistan People's Party (PPP).

The power and influence of the Pakistani army

During the mid-2000s, NAB found ways to drop corruption charges against all those politicians who quit these two parties and joined the one led by Gen Musharraf or allied with it.

Since the controversial election of 2018 that brought Imran Khan to power, the agency has arrested opposition politicians and kept them in custody for prolonged periods.

Government opponents say evidence has yet to be produced that would stand the test of law in a court.

More from Ilyas on Pakistan

- Published28 July 2019

- Published10 January 2018

- Published2 June 2019

- Published19 November 2018

- Published17 December 2017